“‘He’? ‘He’ who?” said Eibhlin, her nerves tensing again and the twisting in her chest returning.

“The Father Abbot!” said the monk. “No, please, you must give me a chance to explain, but we must do that as we leave. Already, I’m afraid we may have been too loud or that the abbot might not be as deeply asleep as I hoped. Please, come! I’ll explain on the way.”

When the three were down the hall a bit, Eibhlin whispered, “Okay, what’s going on? If you don’t tell us, I’m going back to bed.”

“Oh, please, miss, don’t. You mustn’t! I will ex-plain all I can, but first I must know, did you come to this place through Ásdagr’s door? The door of the Lady of Gates?” asked the monk.

Eibhlin’s breath sharpened. “Do you mean Mealla? And how do you know about the door?”

While glancing around a corner, Brother Callum replied, “Is ‘Mealla’ what she is called in your country? Well, Miss Eibhlin, all the monks of our monastery know about the door up the mountain, for we were granted this place for our monastery in exchange for promising to protect the door and Ásdagr’s key.”

“The key?”

The monk slipped around the corner, and Eibhlin followed.

“So, you do want the key, though I suspected as much when I saw you come to this place from the direction of the stairs, rather than the mountain roads. There’s nothing up there but the door, and the one with the key to that door most likely wants the next one.” Callum said. “Unfortunately, you won’t find the key here, but I will speak of that soon. Anyway, our order was meant to protect the key and to give it to one we think trustworthy, should such a figure appear. The records of those who have received the key from us are a secret known only by the abbot, and it seems that every time one of these persons died, the key, through some other magic, always returned. But it has been at least a few centuries since the last time this happened, and in that time, the monastery forgot its duty. The stairs leading to the door were worn away by the wind and frosts, and the monks here became indifferent to their task regarding the key. The previous abbot, Abbot Allan, attempted to restore the order to its proper state and even rebuilt some of the stairs, but, to the detriment of all, he passed before any lasting changes could be made. Worst of all, however, was the establishment of Brother Ormulf as Father Abbot, for not only did he abandon the reforms of Abbot Allan, but he then sold the key!”

Eibhlin felt sick. The key! It should have been here. She should have been so close. “Who did he sell it to?”

Callum stopped, and even in the scarce light Eibhlin could tell he wore a shame-filled face. His voice cracked, “To a fairy your country calls Arianrhod.”

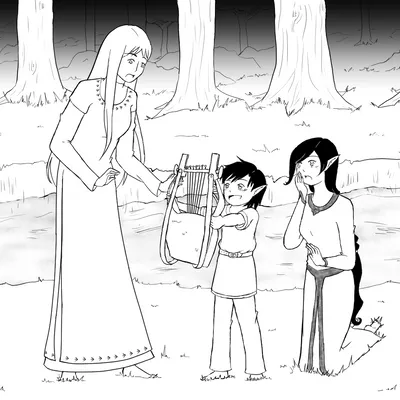

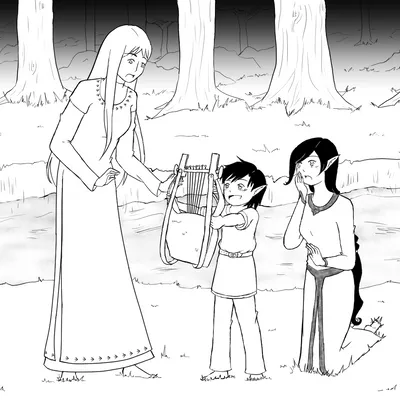

“What!” Eibhlin and Callum flinched as the kithara’s shout echoed down the hall.

“Mel! Shush!” Eibhlin hissed.

The instrument quieted, but its strings tightened and creaked in anger. “He sold Mealla’s key to the Witch of Hours?”

“Yes,” said Callum. “He did.”

“Witch of Hours?” Eibhlin asked.

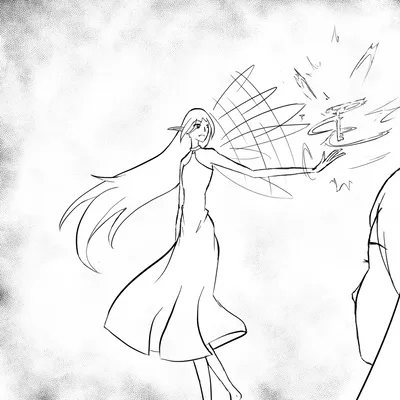

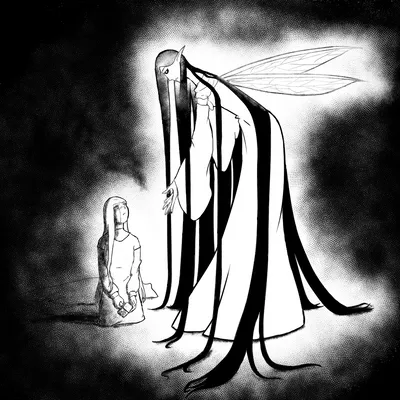

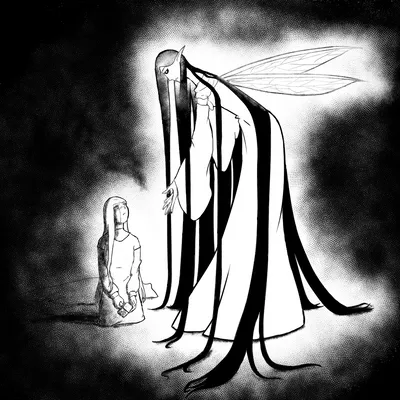

“Arianrhod is a wicked, despicable witch! A fairy who betrayed her own people and helped the Fae Moon rebel against her Sun thousands of years ago. Now, the Fae is sick, and instead of repenting, she has worsened her sins countless fold by practicing black magic of all kinds. There is no fairy more wicked than she, nor any living being who hates Mealla more, for Mealla has opposed her since the rebellion,” said Mel.

“And now this witch has the key?” asked Eibhlin.

Callum nodded.

“But why? Why would she want it? She’s not searching for the others, is she?” said Eibhlin.

“Most likely just because it is Mealla’s,” said the kithara. “The Witch of Hours hates Mealla, and hatred does not need a good reason to cause trouble for its object. What I want to know is what the Abbot received for it. Brother Callum?”

The monk looked over to the nearest window, which let in a pale glow. He answered, “The tree. The Witch gave him the tree.”

“The tree? The Tensilkir? The one that calls those wishing to enter the Fae?” said Eibhlin.

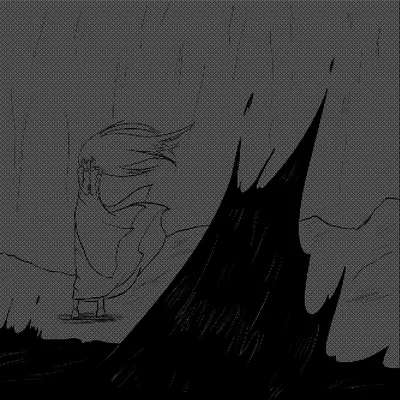

“It does call those,” said the monk, “but mostly it calls the lost, both mortal and fae. They then find their way here and, through various forms of trickery and traps, Ormulf evaluates them, and if he approves of them, he sells them as slaves to the goblin mines.”

Eibhlin’s breath caught, and Mel swore without apology. The girl tried to piece together her thoughts. “He sells… goblin… what kinds of tests? What kind of person is he looking for?”

“Those who will not be missed for a while, I expect,” said Mel. “Milady, did he not seem interested in your status as a solitary traveler? And remember you said that during your conversation you felt pulled in two directions? The abbot may have used some herb in the food or drink or some enchantment to make you speak more freely than you would otherwise.”