“Mealla—”

“'Lady’ Mealla,” whispered Mel.

“Lady Mealla,” Eibhlin corrected herself. “My reasons are simple. When I sold my father’s hammer to you, I didn’t know it was something important to him, but it is. My mother died when I was young, and it’s something that belonged to her and so is important to my father. Again, I didn’t know that, but now that I do, I can’t let Papa lose it on my account! I… Lady Mealla, I want the hammer back that I traded to you. Here! I have your purse—oh! And I never used any of your treasure or anything! I promise. Now, please, I’ll return this to you, so please return my father’s hammer to me.”

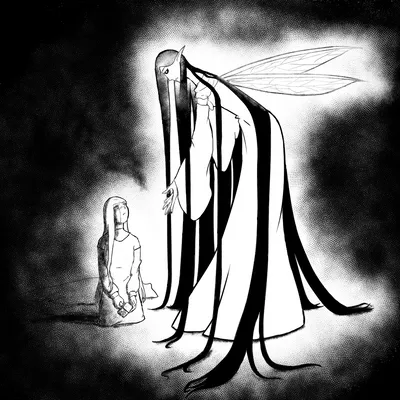

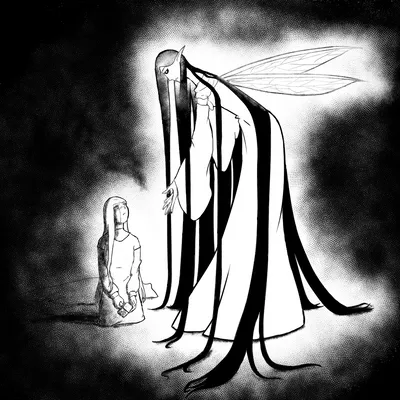

“I refuse,” said the Lady without hesitation.

Eibhlin gaped. “Wha… why? I promise, I really haven’t taken any of your treasure. I’ve barely even touched your purse. Why won’t you trade it back?”

“Because I don’t want that purse or my treasure as much as I want the hammer,” the fairy replied. “I’m sure your musical companion has figured out why. I find it unlikely that the Messenger would miss the reason why a fairy would desire a particular enchanted hammer.”

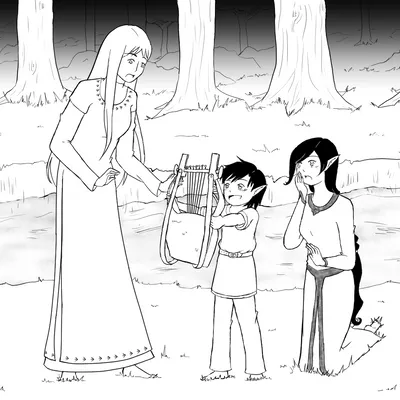

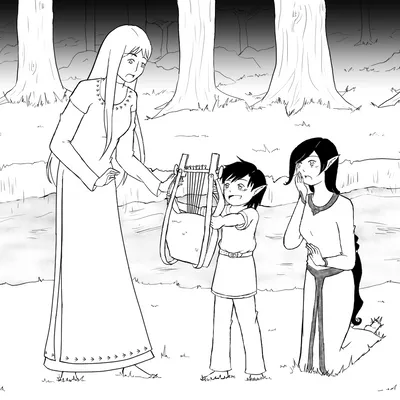

“Mel? Mel, what does she mean?”

Mel spoke slowly. “If my guess based on your description of the hammer is correct, then it is none other than that which forged the tools that carved me and, indeed, which fashioned my plating and metal: my master Chimelim’s first magical item, Chimelim’s Hammer by which he crafted all his remaining works. I knew my master had foolishly gambled it away after getting drunk, but I had never expected to accompany the last human hands to hold it on her quest to reclaim it. I could not be sure, however, so I did not speak of it, but now my suspicions are confirmed.”

Eibhlin’s eyes widened, and she stared at the fairy, speechless.

“Did I not say it was priceless?” said Mealla. “Something of that magnitude, there is little I would withhold to possess it. And as I said that night, humans have no use for it. If you were dying in a desert, would you not forsake diamonds for a cup of water? Likewise, the riches I offered were more valuable to you than the hammer, and the hammer more valuable to me. As such, even if your scale of value has changed, mine has not. I refuse to return the hammer.”

“B-but I’ve gone through so much to get here!”

“That was your choice.”

“And that hammer really is important to my father!”

“Changed circumstances do not invalidate our previous transaction. We laid out our terms, found an agreement, and exchanged our goods. Our deal is already made.”

“But it wasn’t mine to make! By selling it, I stole my father’s happiness. Now, he’ll be miserable forever. Please! I can’t do that to him. I just can’t!”

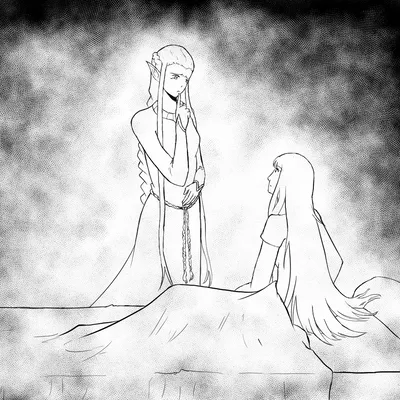

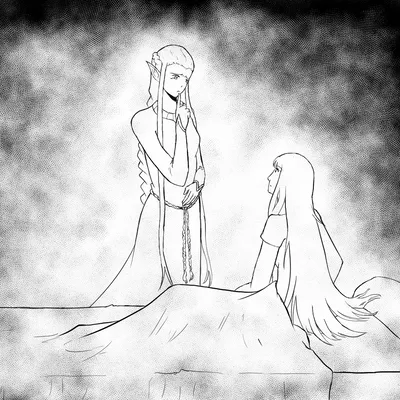

Eibhlin choked back sobs while the fairy watched her with an impassible expression. Several minutes passed. At last the Lady said, “Very well. I shall return Chimelim’s Hammer.”

“Then—”

“However!” the fairy said in a voice that slew the happiness that had entered Eibhlin. “However, if what you say is true, then you have not only betrayed and dishonored your father, but made me an accomplice in your actions. As such, you have forfeited the right to state your terms of recompense and so must agree with my demands of compensation for not only the item you are reclaiming but also the personal injury done to me. Do you understand?”

Hearing the commanding tone, indignation sprouted in Eibhlin’s chest. “Why are you doing this? After being so kind about the things I’ve gone through, now you’re being harsh about everything!”

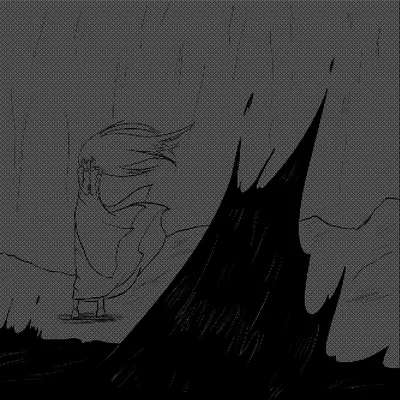

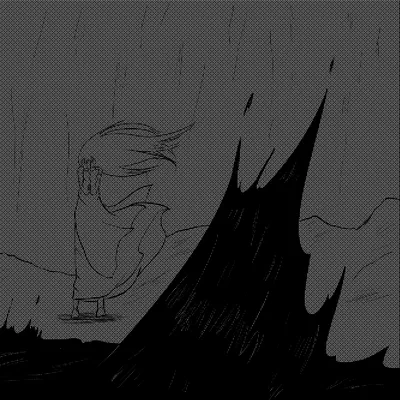

The fairy’s voice barely changed as she spoke, but the very hardness of it shook Eibhlin’s bravado. “Justice is not kind, human child. That is why humans demand mercy. Now will you accept or reject my terms? If you reject them, know that while you do rightfully own those keys, and so I cannot prevent your coming here, this is still my realm, and I can easily kick you back out.”

Whether it was courage or recklessness, Eibhlin did not look away from the fairy. Steeling her own voice, she said, “What do you want?”

“A price befitting the crime,” said the fairy. “You say that the hammer is a memento of your mother, a memory of her kept by your father. Therefore, by selling it against your father’s wishes, you betrayed your father, indirectly your mother, and your father’s memory of her. My price, then, is this: the memory of yourself as Lochlann the blacksmith’s daughter.”

“What?” came both Eibhlin and Mel’s voices.

“Lady Mealla, you can’t be serious!” cried the kithara.

“Melaioni, Protector of Understanding, Messenger of History, do your tales portray me as one who would make such a statement lightly?” said Mealla.

“But you can’t—Milady Eibhlin, you can’t really be considering this!” said Mel.

“I don’t even understand it,” said Eibhlin. “What do you mean by memory?”

“I mean,” replied the fairy, “that anyone, any living being at all, who knows you as Lochlann’s daughter shall forget you, shall forget the you that is his child and anything related.”

“I’m still not sure I understand. And why would you even want that? What good are memories to you?” asked Eibhlin.

“Memories are a far more potent force than you may think,” said the fairy. “I can find several uses for them. Now—”

“By ‘anyone,’ does that mean me, too? And Mel?”

“Yes, you, too, shall forget,” said the Lady. “As for Melaioni, I would not be so ignoble as to obstruct the honesty of the Messenger’s records. However, it shall not be able to share such knowledge with you. Not to the day you die. Are those all your questions?”

“Yes. I think so. I accept your offer,” said Eibhlin.

“Milady!” cried Mel in such a high pitch its strings nearly snapped. “Milady, please, give yourself time to consider! Think of the implications! You shall have no home, no family! You won’t remember anything about them! Think of the regret!”

“Mel, I must return Papa’s hammer to him,” Eibhlin said. “Lady Mealla is right. I did something horrible to him. I… I sold his memory of my mother, Mel. I have to make it right! I know it sounds terrible, but I have to return the hammer, no matter what!”

Mel gave no reply.

“Are you sure of your decision? Once the deal is finalized, there will be no chance to regret or reverse your choice,” said Mealla.

“Will I even remember this decision?” asked Eibhlin.

“No. You will not,” said the fairy.

“Then I’m sure. Lady Mealla, I accept your price,” Eibhlin said.

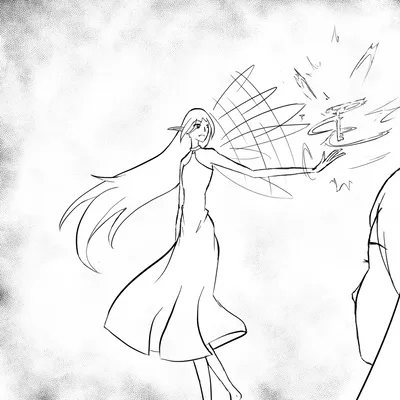

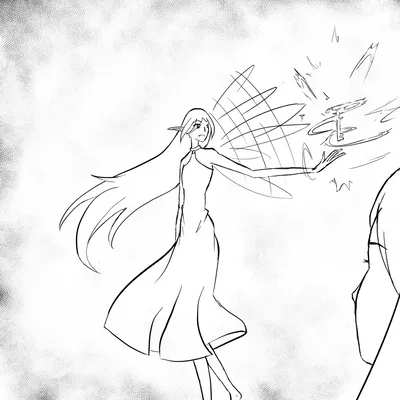

“Very well.” The fairy lifted her hand, and the hammer appeared in a flash of light. She held the item out to Eibhlin and said, “Take it. You shall not recall the price or the reason for your quest, but you shall remember enough to complete your mission. Bring this to your father, and return it to him. The moment he takes it, the deal shall be finalized. Do you understand?”

“I do,” said Eibhlin.

“Then I shall return you to the door through which you entered. May you find what you seek at your journey’s end.”

As the fairy spoke, light gathered around the hammer in her hand, and when the last of the words faded, the light shot out and wrapped around Eibhlin like a cocoon. Wood, water, fairy, all vanished as Eibhlin was swallowed by the light.