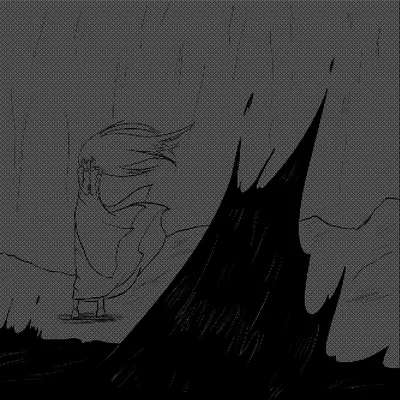

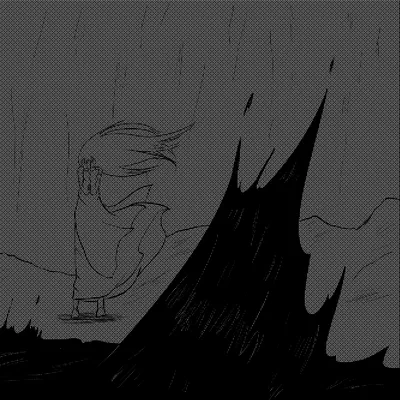

Fire and screams rose into the air on the other side of the door. The clash of metal on metal and stone echoed on the mountainside. Willow-like branches hung withered or burning under the dark sky. Figures darted here and there, some in robes and other, smaller ones leaping at them.

Something felt familiar about this place, but to Eibhlin’s fever-filled mind, it all looked alien. She could not even process enough to be afraid but only lay upon the dry earth, coughing and moaning for help. Her vision blurred; the smoke burned her nose and throat; the dry air parched her lips. A thought, distant enough to lack emotion, came into her mind.

She was going to die here. Whether by fire or sword or sickness, she was going to die.

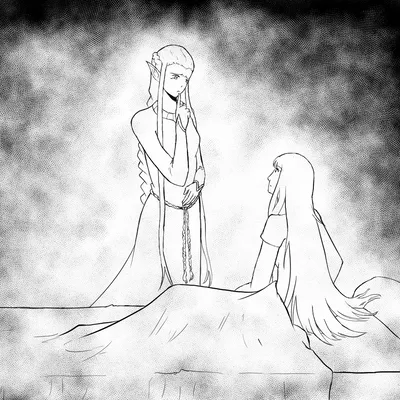

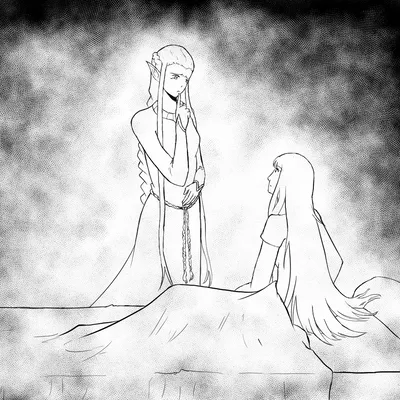

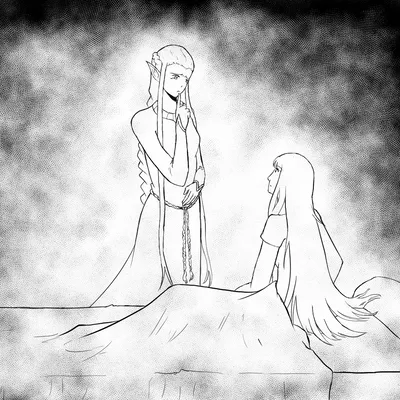

The thought had nearly reached full consciousness when she heard a voice call from behind her, or above her; she wasn’t sure. A few moments later, someone lifted her from the ground and turned her toward the sky. High above, the moon shone full from behind the worried face of a monk. He was of middle age, and on his worried brow was a sickening gash pouring blood down his face. He called out something, but between the chaos and her own head’s throbbing, she couldn’t make out the words. The voice behind her spoke again and struck up a conversation with the monk, of which she could only catch a few words and phrases.

Some sort of agreement was reached between the voices, for Eibhlin was soon lying across the monk’s shoulder, moving away from the noise and heat. The next thing she knew, he leaned her against wonderfully cool rock in some dark place, the sounds of fighting fainter but still present. The monk tried to tell her something, but she couldn’t tell what, and then he was gone.

For a few moments, or perhaps a few hours, Eibhlin swam along the shores between consciousness and darkness. Then she heard a sound like a horn and a powerful roar, like thunder mixed with terrible screams. After that, she fainted.

Her sleep was haunted by messes of people and places and she did not know what. She did not know who she was or what she was doing.

Then she saw a man, a man with a bushy beard and always smiling eyes. Except they were not smiling. They were red with grief, and dark circles and bags puffed out below them. He sat kneeling by his bed, holding the blanket to his face to muffle his sobs.

All alone. Nothing left. They had sold everything they could, but it still had not been enough. Now it was all gone. Everything of hers was gone… except one thing. That alone he had not been able to sell. Oh, but if only he had! But he had waited too long. If only he had not hesitated! If only he had sold it! Now it was all he had. Just that one thing. The only thing left that had been hers. Only that. Only that.

The man faded back into the murky mess of dreams.

Eibhlin woke as someone picked her up. With a groan, she opened her eyes. She was in a narrow cleft of rock, sunlight shining upon the wall from around the corner. Weakly turning her head, she saw a familiar face. “Brother Callum.”

The monk looked down at her with sad, concerned eyes, a bandage wrapped around his head and a small, strained smile on his lips. The look of the man reminded her of the man from her dreams, and Eibhlin’s chest hurt. He said, “Good morning, and welcome back, Miss Eibhlin.”

“Whe…re….”

“Hush. Don’t waste your energy. You’re dreadfully sick. We must give you medical attention immediately.”

“S… sick?”

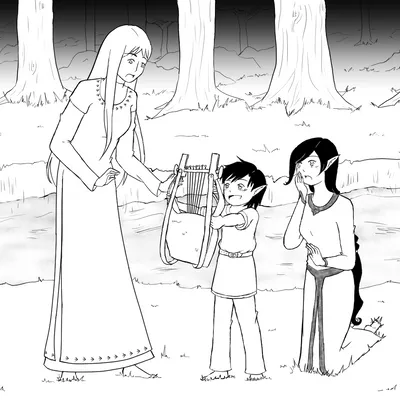

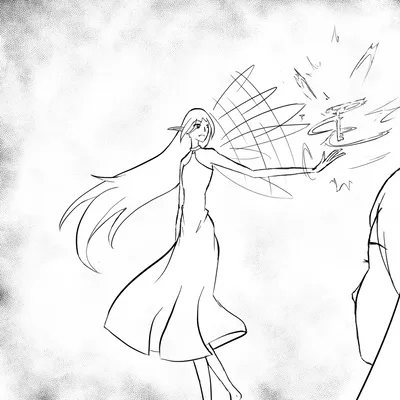

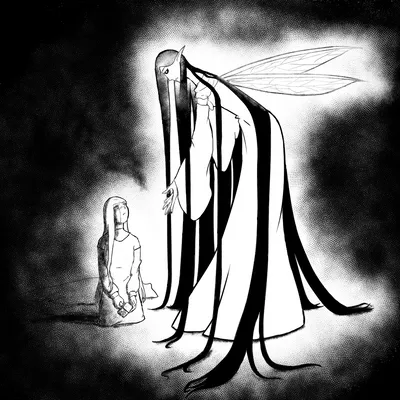

The voice behind her, which she now recognized as Melaioni, answered, “The light of the Fae Moon is poisonous to those of the Mortal Realm and makes them ill, moonstricken. With continual exposure, it can even lead to death.”

“Death….”

“Do not fear, Milady. Natural sunlight from the Mortal Realm weakens and eventually purges the poi-son, and there are other treatments that help. Although… no. No, we will speak of that later, when you are better. Till then, rest, Milady. You are in safe hands.”

Eibhlin tried to nod, but the nod turned into sleep. The next week was much like her time with the elves, except less comfortable and a lot less peaceful. She lay on a cot in a medical tent, her burned hand bandaged, drifting in and out of sleep, sometimes waking for a few hours or for only a moment. On the first day, she saw a cart piled with the corpses of small, terrible creatures pass the opened tent flap. Her horror banished sleep until someone gave her a sedative. The rest of the time, she would wake to hear the sounds of shovels and solemn chanting. Always chanting. Singing the buried’s departure. Every time she woke, there was always singing.

Gradually, her strength returned, but when she tried to get up, those working among the infirmary would insist she rest a bit longer. Even after a few more days, when she felt completely cured, except for the occasional throbbing in her burned hand, those caring for her would keep her in bed and give her medication to help her rest. She tried to do as they said, but after so long in bed, she was restless.

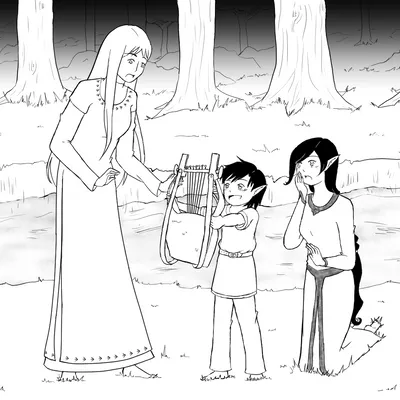

At first, she occupied her time with observation, but there wasn’t much to look at. There was no decoration, only those still injured for whom there had been no room in the nearest village or whom no one dared try to transport down the mountain. She had already noticed by now that most of those assisting her and the injured were not monks but laity. There were even a few women. The assistants came regularly, but neither side could understand the other’s words to the level of decent conversation. She did manage to learn, though, that Mel and Callum were away somewhere.

This last point especially irritated her, as she had something she wished to ask the kithara about. She had noticed it a few days before out of the corner of her eye when turning in bed. Her hair was not white as when in the Fae. Instead it was dark, dull, stormy gray, nearly black, the color of moonlit clouds. Or at least, most of the time. Over those days of examining her hair, she had noticed that the color actually shifted, starting out dark earlier in the day and growing lighter as the hours passed. She didn’t know if the color ever returned to white, as the infirmary workers always gave her medicine when it had faded to about half the darkness, but Eibhlin wondered, and the long days lying awake without company bored her. So, finally, she snuck out of the tent.