She took in the mass of buildings of aged white stone turned grayish blue in the twilight climbing up toward a palace at its center. Roads lit by torches branched out away from the gate, people still filling the spaces between shops and homes in the growing dark. Around it all rose the white walls, and on the western side she could still catch the silhouettes of ship masts peaking over the walls. She tried to guess how many people must fill the homes and roads within the walls, but she couldn’t conceive of a number that felt large enough. Finally giving up, she started toward one of the roads when a voice called out behind her and an armored hand came down on her shoulder.

Fear spilled back into her. She spun around and saw a pair of guards. Had she done something wrong? Had she made a mistake with the customs officer? Had they thought her a member of a minstrel guild instead of a lone traveler and wanted to see her papers? Had she seemed suspicious in some way?

When the guards started speaking, her panic rose. She couldn’t understand them. Words flew at her, but she couldn’t respond. After she said nothing for several moments, one of the guards changed his tone, and they started talking between themselves. The first guard turned back to Eibhlin and began slowly listing off countries as questions. When at last he said “Enbár,” Eibhlin nodded. A grin lit up his face, and he tossed a few more sentences to his part-ner before speaking to Eibhlin again. His accent was heavy and not one she could place, but comprehendible.

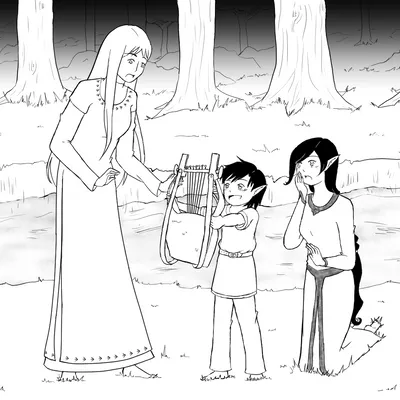

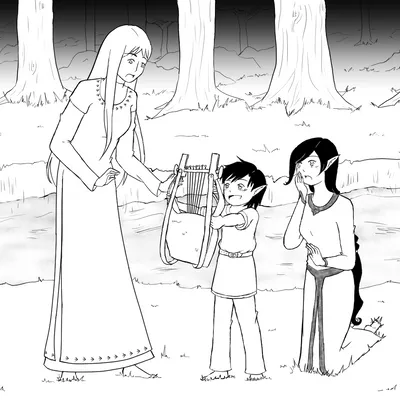

“You… you are music? No, how do you say? Bard! You are a traveling bard?”

The kithara warmed against her back, and Eibhlin felt obliged to nod. The guards appeared impressed, and another short exchange broke out between them. The second guard stepped around her and stared at the instrument on her back. He said, “Show us.”

Eibhlin tensed, and the first guard reprimanded his partner before saying to Eibhlin, “Sorry. Enbár’s words? Language? They are not… common here. He means… means… please play. Please?”

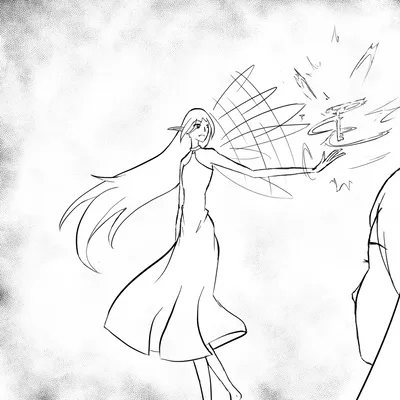

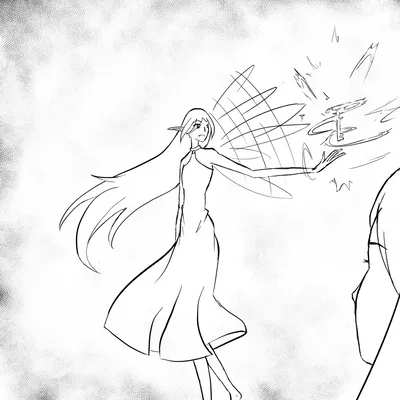

Eibhlin wanted to run, but if she did, what would the guards do? Would they chase her? Throw her out of the city? She didn’t even know how to play an instrument, but what could she do under such expectant eyes? Trembling, she took the kithara from her shoulders, hoping as she held the bulky instrument that she could just pass for a mediocre musician and move on into the torch-lit city. However, as she reached to pluck the strings, she suddenly felt calm, and her thoughts slowed. Her fingers slipped from one string to another, sending a soft ballad floating into the twilight. The notes filled her thoughts and flowed from thought to fingertip and back as she played. Once the last notes disappeared, Eibhlin’s thoughts returned to sharp clarity, and despite the delight of the guards, cold panic overshadowed her. Giving a curt farewell, she dashed into the city, the confused exclamations of the guards falling behind her.

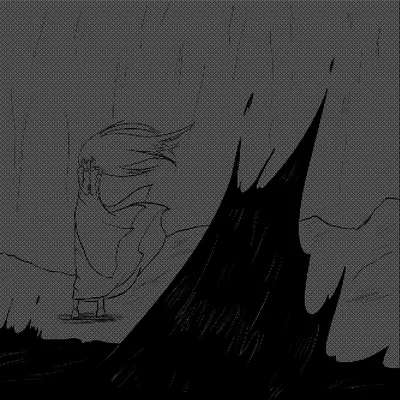

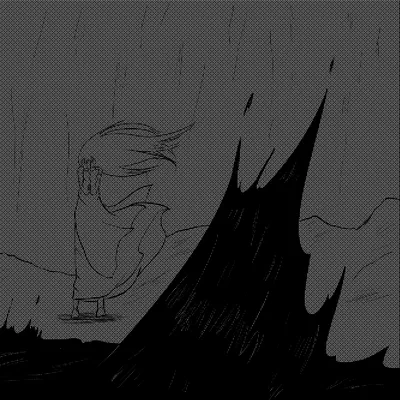

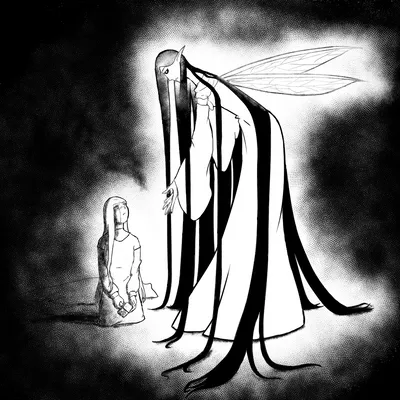

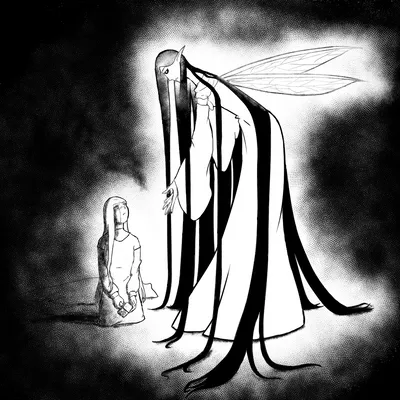

After a while, she turned from the now sparse road into an alleyway and collapsed against the wall, hugging the kithara to her chest as she caught her breath. She said, “What… what just happened. Harp, tell me right now!”

“Milady, please recall that I am not a harp but a noble kithara, and my name and vocation is Melaioni,” huffed the instrument. “As for what just happened, you need not fear anything. I guessed by your hesitation and how you held me that you did not know how to play me, so I guided you. Small magic like that is fully within my abilities.”

“You controlled me!”

“To a limited extent, yes. However, should you have wished to, you could have easily denied my guidance, and I cannot extend this magic beyond playing me. You see, I cannot play myself, so my craftsman gave me the ability to bestow skill upon my minstrel for the sake of performing my craft. I swear upon my honor as a true historian that I can do nothing else of this kind and cannot do so absolutely,” said Melaioni.

“Really?” said Eibhlin.

“I can give no greater oath than that,” it said. “Even should my conscience snap like an old string, I would never break such an oath. If you still do not trust me, I apologize. I did not think you would be so frightened. Most are not, after all, to learn they do not need skill to make money. I promise I shall not guide you again without your asking.”

“You really won’t?” said Eibhlin. “If you do, I’ll leave you sitting on the side of the road. Got it, Mel?”

“‘Mel’? It has been a while since I have worn that nickname. But, yes, Milady, I promise,” it said. “I do not want to be thrown away. It would be quite unproductive.”

Eibhlin almost smiled. She then glanced out to the nearly empty street. Dull blue lay over everything, broken only by orange orbs of torches lining the road at regular intervals. The cobblestone beneath her was cold and the air comfortable. She slumped forward with a sigh.

“Milady, are you unwell?” asked Mel. “Should we not find an inn? In a port city like this, we should be able to find some place that speaks your language, or I can reveal my nature and act as a translator. But we must be quick. The night darkens.”

Eibhlin frowned. “I was just going to sleep here.”

“What?” the kithara said. “Milady, for a young woman to sleep in an alleyway, what is more in a port city, is not safe!”

“But I don’t have money,” she said. “When I left home, I didn’t think to grab any.”

“You did not ask the elves?”

“Why would I ask them for money?”

“What about Mealla’s purse? You could withdraw some coins from there,” said Mel.

“No!” Eibhlin said. “I can’t do that. If I use it, if I take any money from her, she might not let me return the purse. I’ve seen that before from merchants, and I can’t risk it.”

Mel was silent for a time then said, “Very well. I see your concern. It is likely too dark to safely search out a convent, as well. If you really insist on sleeping outside, then you should go up the hill toward the palace or back nearer to the gates where there are more guards.”