There is a strangeness that comes with awe. Namely that awe is a terribly humble state. The more one’s feelings move toward awe, the more complex they become till, in the purest of awe, there is a striking similarity to terror and grief and less of what one might call ‘happiness’. Happiness must then transform into joy if it is to survive more than a mere moment in awe’s presence.

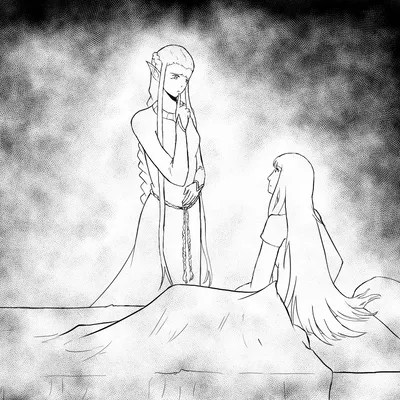

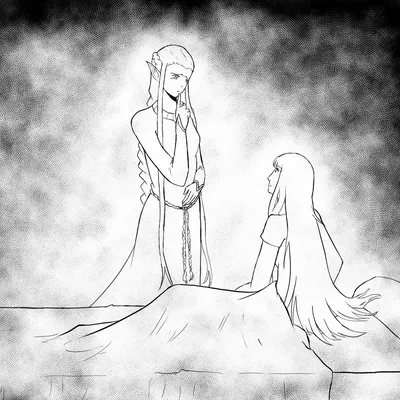

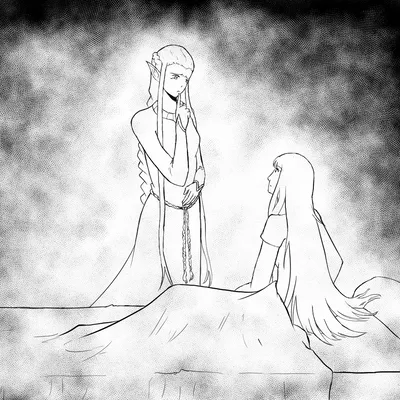

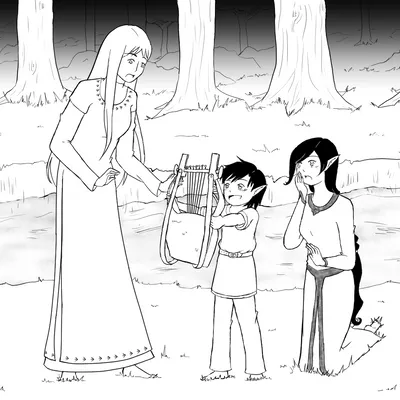

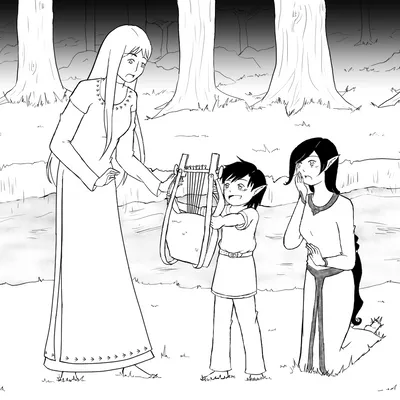

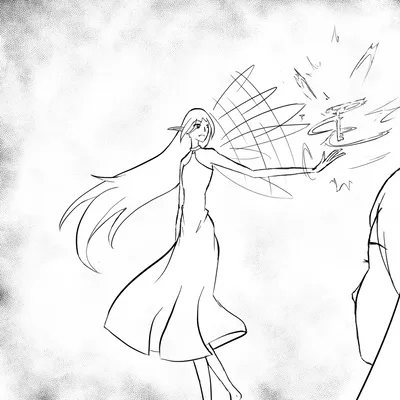

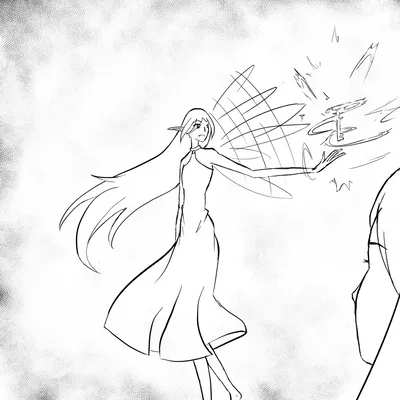

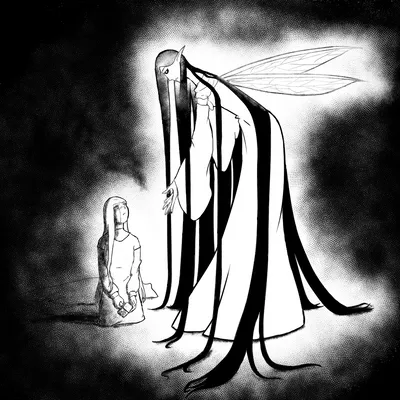

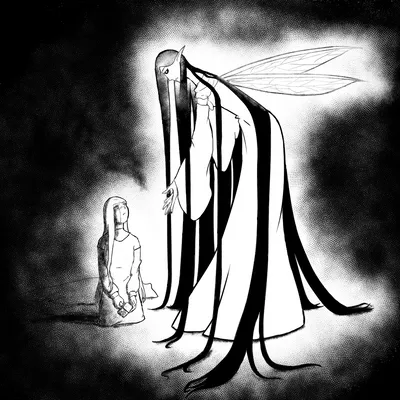

The emotion Eibhlin experienced now was somewhere between wonder and awe. When she had met Mealla that inciting night, she now realized, she had not really met the Fairy Lady, only a fairy far from home. Here, in her home, in the realm which she was meant to occupy, the girl saw the fairy for herself. The arms of the Fairy Lady, once so dainty and fragile, now spoke of health and strength, the fingers of crafts and skill and grace far beyond the capability of the thick, stubby sticks of human hands. Her legs were like the trunks of saplings, lifting her toward the sky. Large, bright eyes shone like the morning star in the early light of dawn, and sunlight glistened off her dark hair as though it were home to astral lights. The Lady gently plucked a prism from the tree and bit into the fruit, making Eibhlin think of elves and churches and bell towers and made anything Arianrhod, the Witch of Hours, could do, any spell or incantation or curse or magic, feel like a farce.

“Mealla,” she said.

“That is what your countrymen call me,” replied the fairy in a voice that sent Eibhlin quivering with some unknown emotion that brought tears to her eyes.

“Lady Mealla, great Fairy Lady of Doors and Crossroads, Noble Rebel to the Moon’s Rebellion,” came Melaioni’s voice, “My Lady Eibhlin requests an audience with you.”

Eibhlin, brought out from her stupor by Mel’s earthly, rustic voice, said, “Y-yes! I need to talk to you about—”

Her words died out when the fairy suddenly drew near and took the girl’s scarred hand within her own. Mealla held it as though it was a baby bird, and Eibhlin more felt than saw the tinge of sadness in the fairy’s face. “Take your hand and place it in the stream. Keep it there until it cools, and not a moment earlier. We can speak afterwards.”

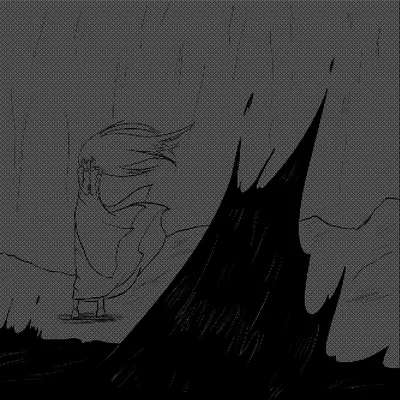

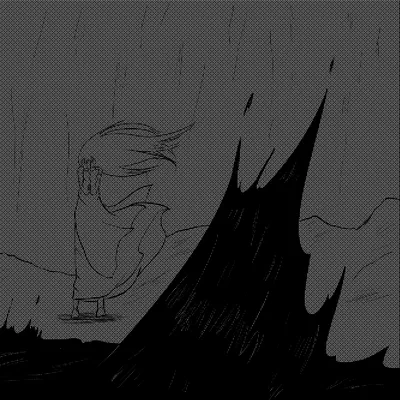

With that, the fairy let down Eibhlin’s hand and watched. Eibhlin knelt beside the giggling brook. She glanced back over her shoulder, but the fairy only looked back with expectant eyes. Gingerly, Eibhlin lowered her hand beneath the water’s surface. All at once, intense, burning pain shot up her arm and to the rest of her body. Reflexively, she started to yank her hand back as from a flame, but the fairy’s voice cut through the pain straight to her thoughts.

“Don’t remove your hand! You must keep it there until it cools!”

Gritting her teeth and fighting all instinct, Eibhlin braced her right arm with her left and forced her burning hand deeper into the water. Time seems to slow in moments of great physical suffering, so Eibhlin couldn’t know how long she endured the pain, only that she did so because any time she faltered, the Lady’s voice broke through again to remind her of her task. Finally, her hand began to cool until the water felt not like fire or even a sun-heated pool but like the chill valley river from the northern mountains. Her body relaxed as the last of the feverish pain faded away, and once it was gone, she lifted out her hand. There it was, as though it had never faced hardship, without callous or scar or burn. It was a hand the likes of which could not be found even on a noble lady of a king’s court. Eibhlin stared in wordless wonder.

The fairy knelt beside the girl and dipped her own slender finger into the water. In a voice that harmonized with the water’s speech, the Lady said, “The sap of the Tensilkir is acidic, and the burns it causes do not heal quickly, nor often very well. However, this water heals and restores in proportion to the great-ness of the injury or distortion. It must be done all at once, however, and so is very painful.”

“What would have happened if I’d taken out my hand?” asked Eibhlin.

“That is hard explain in full, but one thing is certain: your hand would have remained half-healed for the rest of your life, beyond the skill of any doctor—human, elf, or any other—to cure. Furthermore, for each injury, the water only works once, so there would be no second chances. Nor can it cure just any distortion.” The Fairy Lady softly lifted a lock of Eibhlin’s hair that, even in this fullness of sunlight, remained dull. “There are some things beyond this streams power, and beyond my own.”

Eibhlin, too, reached up to her hair. “So I really will have this sickness the rest of my life?”

“I, too, am but a creature, human child,” said the fairy. “There are ancient magics and sacred contracts I dare not try to break. But come. You wished to speak, and I shall listen. And do not think I have forgotten you, Eibhlin of the Border Town of Enbár. I knew you sought out my keys from the moment you obtained the first. What I wish to hear, and what I believe you wish to tell me, are your reasons why.”