Before Eibhlin could ask his meaning, Chensil spoke to his son, and the boy released his father’s hand and sped down the stairs. “Where’s he going?” asked Eibhlin.

“To tell my wife and daughter of your coming,” Chensil replied. “Guests should receive a proper welcome.”

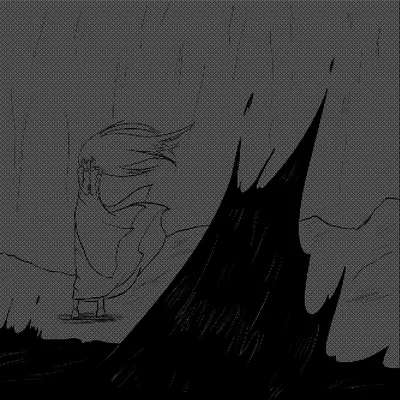

As they followed Elkir’s path, Eibhlin looked back to see the building they had left, and her steps stopped. Beyond a low, white building stretching for what seemed like miles, trees towered, their branches twisting together so tightly Eibhlin could barely tell one from another. They bridged the river, creating a green-tinted tunnel from which the water came. And beyond even that, far in the distance, stood mountains whose tips hid behind clouds. Eibhlin’s lungs felt too small for the air she needed, and she wondered how any could stand living between those encroaching giants and the overwhelmingly vast sky.

Chensil’s voice interrupted her silent wonder. “The Hall was here before we came. Its enchantments hold the forest at bay, though what craft could hold back such trees is lost to us now. The river then comes down from the peaks of the Northern Mountains, through the forest, and into open space, making this a place where boundaries meet. That’s probably why the Hall was built here, as a meeting place between the Mortal and the Fae.”

Eibhlin nodded. For the next few minutes, she walked backwards, taking in more of the long building standing like a wall between the prairie and the forest. It was unadorned, with a simple roof and plaster walls, yet even with its short stature, as Eibhlin continued looking at it, she began to imagine it standing defiantly against the trees and the mountains, and she felt her breath come easier again.

Chensil took her along a path by the river. After passing a few homes and children too distracted by play to pay them any heed, they came to a large house resting beside the water. Green grass and wild flowers bordered the path, and the red wood of the house’s door seemed to soak in the warmth of the air.

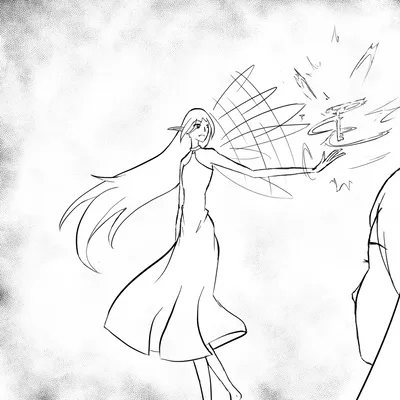

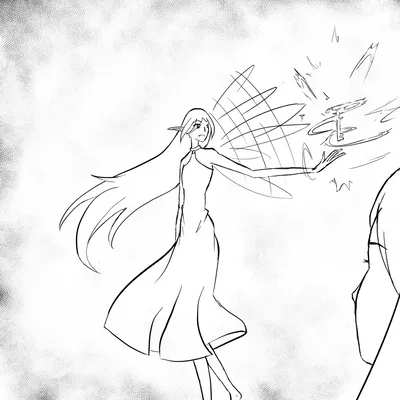

As that same warmth seeped into her, Eibhlin sensed something else filling her. Here, she could find comfort, it told her. Before the feeling overcame her, however, she recalled her father crying her name, chilling any kind of warmth in her. She could still sense the desire to listen to the place, though, to let her concerns go. And because she could sense it, she felt discomfort, like placing chilled fingers beneath warm water, a stinging warmth that also causes pain.

Inside, Chensil directed Eibhlin to a room off the entry hall where a beautiful elf woman placed plates around a table. From another room came a younger she-elf carrying a slender flask. Noticing her guest, the lady quickly beckoned Eibhlin to a seat. “Why didn’t you announce your arrival, dear husband?” she said, a playful laugh behind her chiding. “I’m too unkempt to receive such a guest. I would’ve changed had I known.”

“I sent Elkir,” said Chensil.

His wife almost smiled. “Yes, but when? As you reached the river? You mustn’t think five minutes enough difference to prepare both the table and the host.”

After a kiss to her forehead, Chensil replied, “Nonsense, Yashul. Both are lovely, as always.”

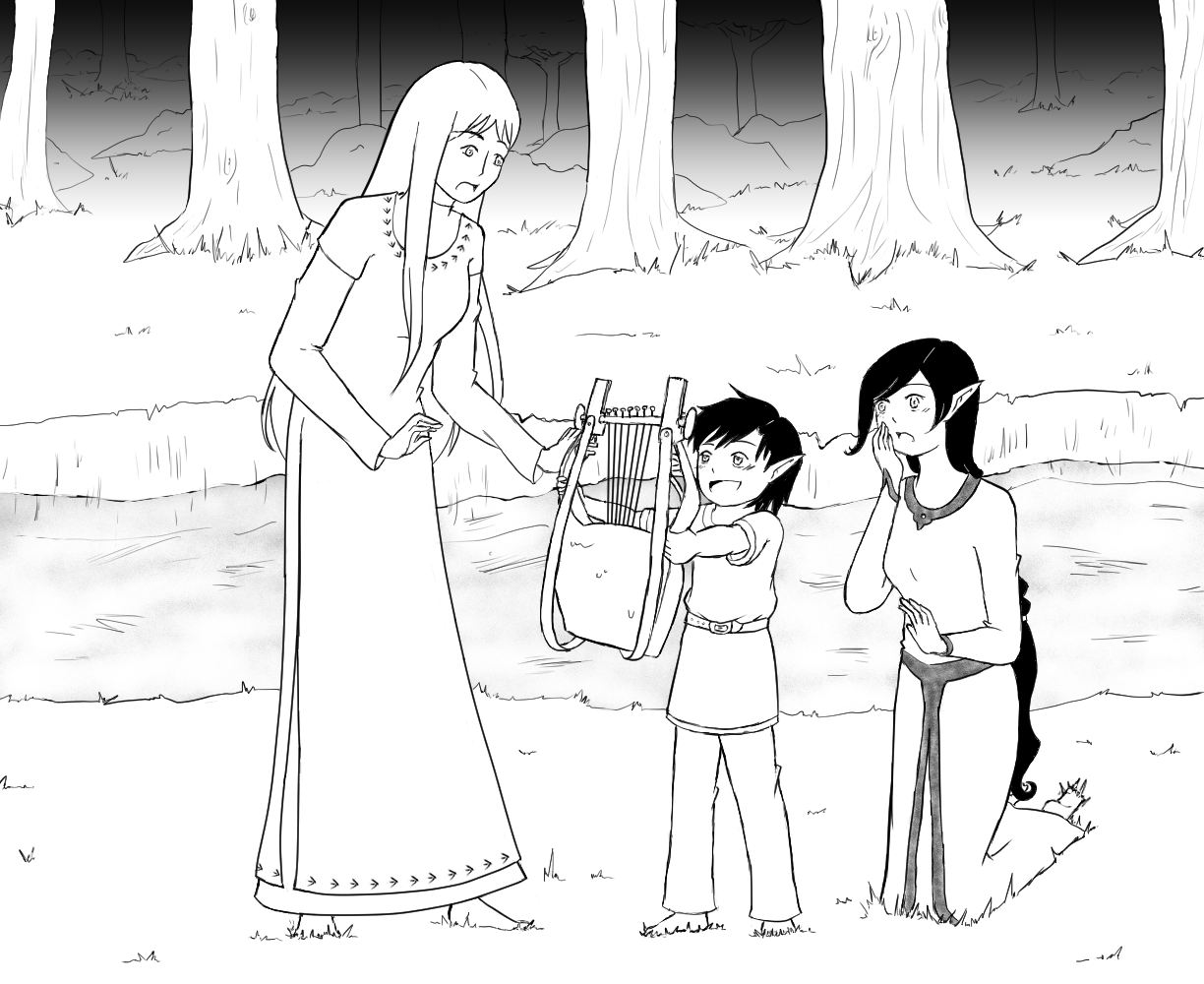

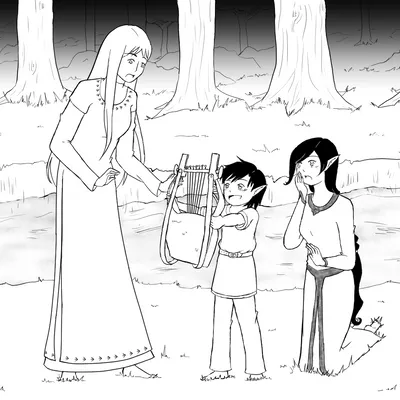

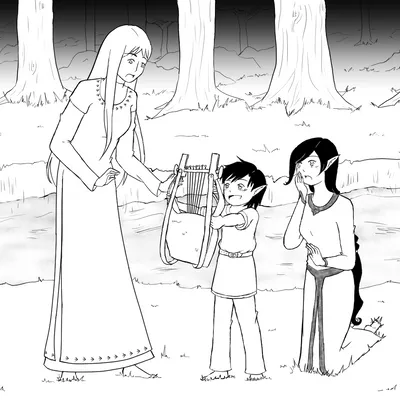

As they spoke, Elkir entered carrying a plate of sliced bread, which the other young elf helped put on the table. Yashul offered Eibhlin a drink as the others sat. The drink smelled crisp as fresh snow and tasted sweet. They passed around the bread and a bowl of fruit as Chensil made introductions. “Eibhlin, this is my wife, Yashul, and our daughter, Elshiran. You have already met Elkir. Yashul, Shira, this is Eibhlin, a human who just arrived through Mealla’s road.”

“Really?” said Yashul. “If I may inquire, Miss Eibh-lin, how did this come about?”

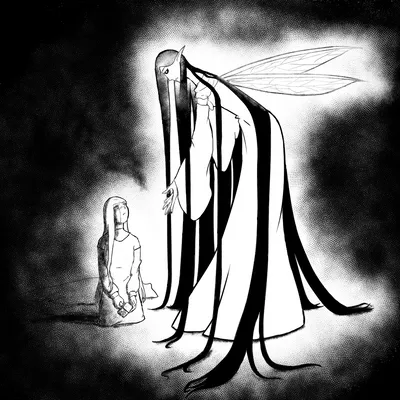

“I’m looking for Mealla, and a fairy I met told me I needed to come here first,” said Eibhlin. “But why do you call it ‘Mealla’s road’? The fairy that sent me here said it was just a normal fairy road.”

“It is, and it isn’t, in a way,” said Chensil. “It is an ordinary door and road and functions as such, but it’s also a road Mealla herself made. I don’t know that many fairies remember that. They often forget who made which door, but they can feel it, which is probably why there are so few fairy doors in the area. But we remember, and we have kept watch over the door and kept it in good condition precisely because Mealla made it millennia ago. Anything she leaves in the Mortal Realm mustn’t be treated lightly.”

“Why do you wish to meet this fairy?” asked Yashul.

“I need to speak with her.”

“And for that you, a human, entered a fairy road?” said Yashul. “This conversation must hold great importance to you. But you said coming here was your first step. Do you know your next?”

Eibhlin nodded. “Yes, I think so, but I don’t know how to go about it. Chensil, sir, you said you were the ‘caretaker’ for the wardrobe, right? Have you heard anything about a key?”

“Key?” he said.

“Yes. A special fairy key. The fairy I met said I need to find a fairy key Mealla made. Have you heard anything about it in your work?” said Eibhlin.

“No, I haven’t. I’m sorry. If there is such a key in the area, though, I should guess it is somewhere near the door. Fairies usually prefer keeping their treas-ures within reach, so she wouldn’t want it far from the wardrobe, as that is one of the few fairy doors here. I cannot say anything with certainty, though.”

“I see. Thank you,” said Eibhlin. “I’ll just have to look around, then.”

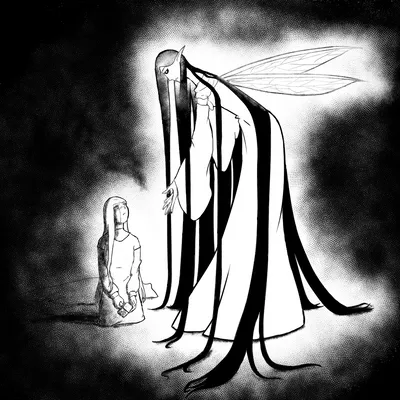

For the first time since Eibhlin’s arrival, Elshiran spoke. “Shall Elkir and I help you look, Miss Eibh-lin?”

“No, I’m fine,” replied Eibhlin. “I don’t want to trouble you. I can do it myself.”

“I advise against that, Miss Eibhlin,” said Chensil. “Can you speak any language besides your own? No? Well, there’re many here who are the same, many who don’t speak your human tongue, many who don’t need to. Shira and Elkir know the language, and they know the settlement and people. You, on the other hand, are far from home, child of man. Act with that in mind.”

Eibhlin wanted to object, but she couldn’t think of a response. “Okay. Thank you,” she said.