Evening came. Over the fire bubbled a pot of soup. Between facing sets of tableware sat a small jar of jam and leftover biscuits from lunch. Eibhlin pulled over the kitchenware chest as a makeshift bench and fell across it with a deep exhale. Outside, a growl of thunder threatened rain as moist wind pushed against and slipped through the window-sheet. Eibhlin smiled. If it stormed, construction would stop. No torchlight work. He would surely be home soon.

The first drops of rain struck against the roof. Time passed, and still she sat alone. But this was expected. Preparing the building sites for the storm and walking the road back home would take time, especially in the dark and rain. This delay couldn’t be helped. Soon, though, her father would burst through the door, perhaps soaked, and go to the bedroom to change. They would hang his clothes by the fire to dry, and he would have stories, of course, of the workers’ sudden rush to defend their sites and of the great works of men’s combined strength.

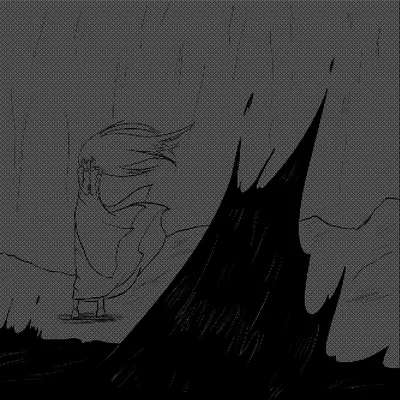

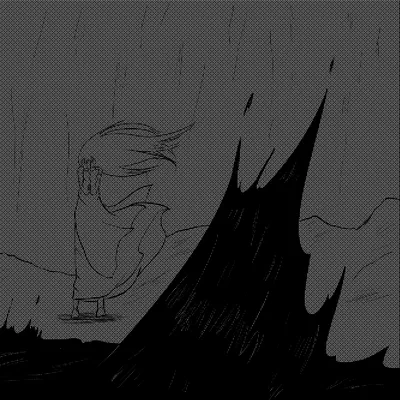

As Eibhlin thought this, the raindrops turned to sheets, and she clenched her sleeves.

The rain fell harder and harder. More than once, Eibhlin jumped up from her makeshift bench to pull out a pot for a new leak. By the time the rain slowed, she had used every spare pot, bowl, and cup, and the only thing to have burst open was the window-sheet, sending her near into panic as she struggled to put it back and stop the water pooling beneath her.

Wet hair stuck to her face as the girl shrank by the fire into a blanket’s folds. She looked to the door. Perhaps the sudden storm had kept him in town. Or had something happened to him? No, someone would have told her. Unless they didn’t know yet. She pulled the blanket over her head, stretched her cold toes toward the fire, and decided clean up had simply taken too long and he was waiting out the rain. Soon. Very soon. Just a little longer.

The rain passed.

Minutes slid away, then hours. Pain settled in her stomach. She removed the pot from the fire to keep the broth from boiling out and watched the steam gradually vanish. Water dripping through the roof reflected the light like drops of fire. Not one thump of boots. Not one creak of hinges. Just the sounds of crackling wood, drips of fire, and a hungry stomach. But not for long. Soon. Just a little longer. A little long—

“Aaaaaargh!”

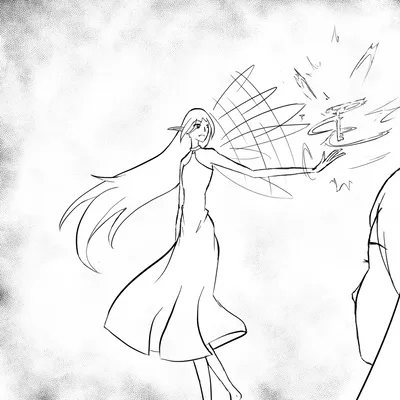

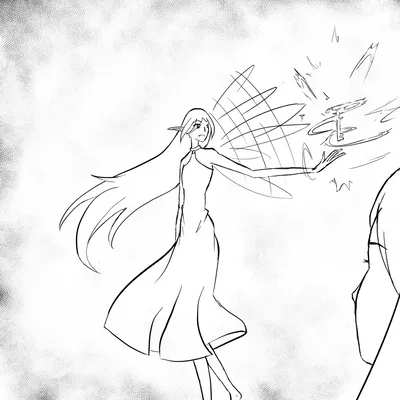

Eibhlin slammed her fist against the floor. She rose, took the broken chair, and struck it against the fireplace. Splinters sprayed across the floor and into the soup as she dashed wood against stone. She tossed the headrest into the fire and stomped to the bedroom.

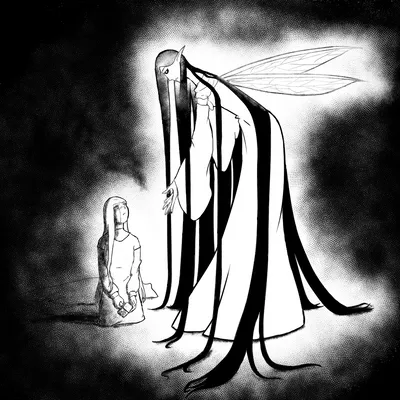

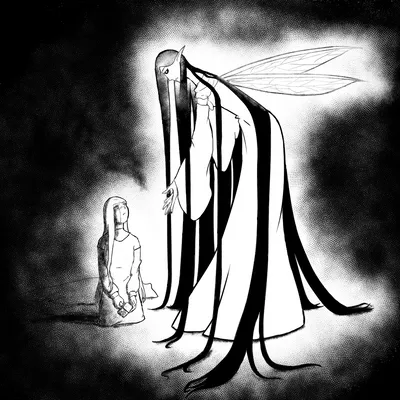

Heading to her father’s side, she turned out the trunk sitting at the foot of his bed. She tore the blanket from the bed, and with the last of her strength, she took the pillow and pounded it against walls, beds, and floor till it burst. She sank to the floor, burying her face in the pillow’s remains, goose feathers falling like downy rain.

Again! He had forgotten her again! He said he would be back. He had… he had….

Eibhlin lifted her face. Seeing the room, all evidence of that day’s cleaning gone, she felt a fresh set of tears forming and moved her gaze to the blanket on the floor, as if thinking to hide beneath it. Then she saw it, half-buried beneath the crumpled pile of clothes and blanket. She pulled the blanket up.

It was a small smithy hammer. Her father being a blacksmith, she wouldn’t have found it too strange to keep a spare hammer among his things but for the hammer’s appearance. It was forged of silver from head to handle’s end. Set into the pommel was an icy blue stone held in place by jagged, silver tendrils and two reptilian tails. The tails melted into the naked handle, crossing as they wound up to the head, where each joined a dragon’s body. From the dragons’ mouths, lighting shot toward the hammer’s face.

Taking up the item, Eibhlin thought how light it felt despite its material. Familiarity flittered across her mind. She had seen this hammer before, but she couldn’t remember when. Running her fingers across the dragon heads, she said, “It’s beautiful, but what good is a hammer made of silver?”

“None, it seems, to you, if it was stored is such a manner.”