“You are traveling so much by yourself? That is dangerous work, dear daughter, and forgive my impudence, but you have barely entered womanhood,” said the abbot.

Eibhlin watched the licking flames and the occasional pop of dancing sparks. “I know. But I must.”

“And what business would drive you to such a dangerous journey? You mentioned a need to enter the Fae?” he asked.

Again, Eibhlin felt pressure to tell the truth clash with some sense of caution. “I… I’d rather not say. But please, believe me, Father; when I say I’m only passing through, I mean it. Tomorrow, I’ll be peacefully on my way.”

Eibhlin and the father faced each other. The girl saw the firelight reflect in the monk’s eyes, veiling his reactions and thoughts. At last the priest broke away and stood, saying, “Of course I believe you, my child. Now, the night deepens, and you must be in want of sleep. I shall show you to the guest room.”

The room in question was a quiet chamber furnished with a single bed and one small window letting in the moonlight. Once left alone, Eibhlin put Melaioni on the stone floor and flopped face-down on the bed.

“Well, that was a good performance, Milady. I had not thought you so capable at it, and I cannot say I much approve, but that was skilled lying,” said Mel.

Eibhlin kept her face to the mattress. Lying was easy. She knew it, had known it for years, and hated it. However, this time…. Turning toward the instrument, she said, “When I was being questioned, I kept feeling like I really wanted to answer, but another feeling kept holding me back. It was… weird. Almost like having two voices in my heard pushing against each other, trying to crush the other.”

The kithara took some time to respond. “We should leave here as soon as we can, Milady. It is too dark and cold now, but as soon as daylight breaks, we should be off. I am not surprised by your account, Milady. I do not like how this place feels. It is not right.”

Eibhlin frowned. “What do you mean? To me it feels just like anywhere else.”

“Exactly.”

“Mel, that doesn’t—”

“Pardon me, Milady, but monasteries are sup-posed to feel different. Monasteries, churches, ruins, all sorts of places like those, they have a different- what is a good word- a different ‘atmosphere,’ I sup-pose. Surely you realized this yourself, after the bell tower.”

“What has the bell tower to do with this?” Eibhlin asked, her fingers gripping the sheets.

“You see, Milady,” the instrument answered, “places, be it due to their age, events connected to them, or their uses all possess an unseen element to them, call it a ‘spirit’ or ‘atmosphere’ to the place, for lack of a better word. It cannot be seen, but it can be felt. Most humans can feel it when young, but many either allow their ability to perceive this spiritual reality atrophy as they grow older or fail to train the ability in the first place. I, however, have not. This monastery does not have the atmosphere of a monastery.”

“So there’s something wrong with this place?”

“Indeed, Milady. Something very wrong.”

Eibhlin turned over in silence. Dark elf attacks, a heart eating creature, darkness and cold and wind, and now a suspicious monastery, when would these trials end? She hadn’t even gotten to say goodbye to Shira and Elkir.

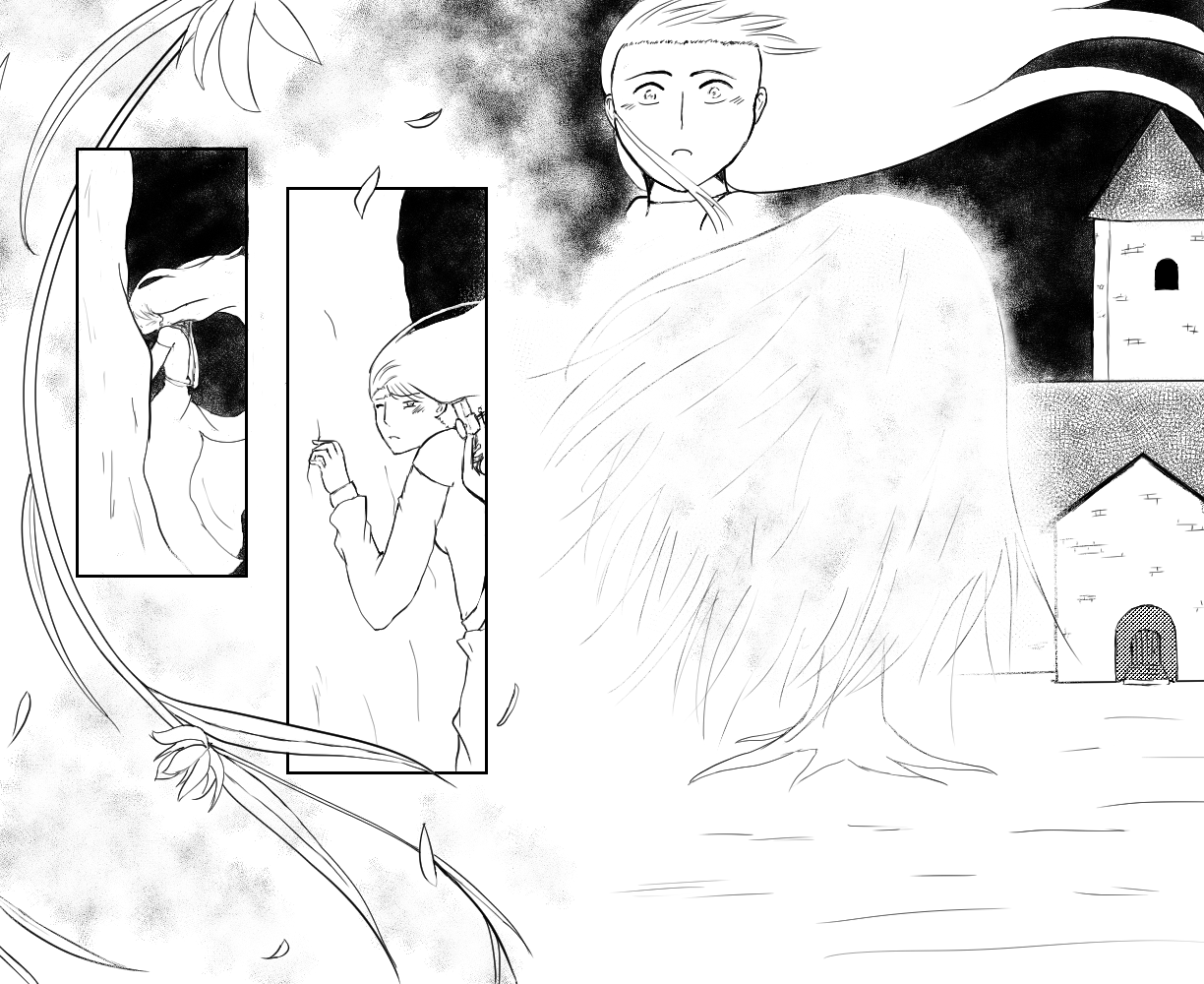

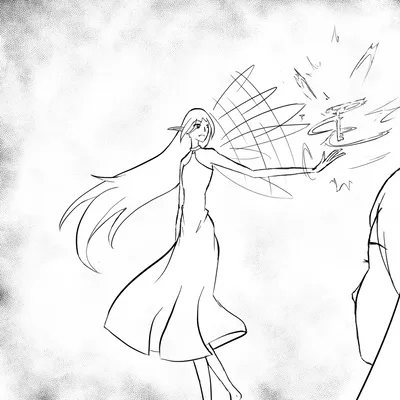

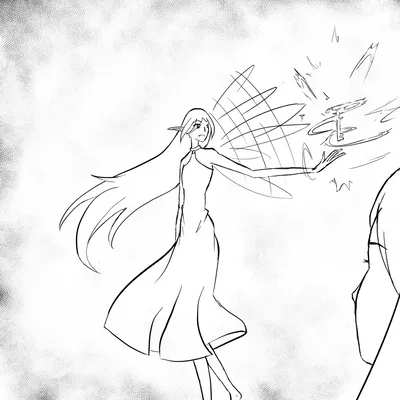

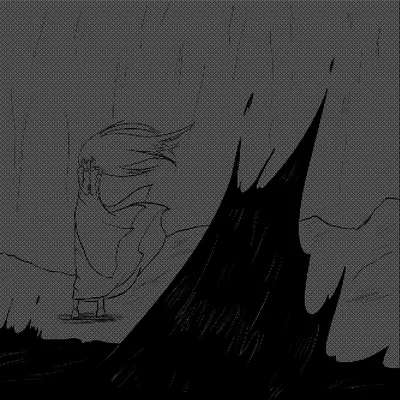

A pang of guilt hit her. Twice. Twice she hadn’t said goodbye. When she felt the guilt turning to tears, Eibhlin pushed away her thoughts and memories. This wasn’t a time to cry. She had to sleep. But try as she might, she could not summon that elusive thing. Thoughts and memories and Mel’s uneasiness swirled together in a storm of confusion and emotion. Even outside it sounded for a moment like the wind broke through the tree’s barrier, chilling her room, and she tossed and turned in the night. A couple hours later, the door to her room creaked open. Eibhlin stiffened. The soft pad of bare feet on stone approached her, but before she could decide what to do, Mel’s tenor struck her ears and made her tumble off the bed in fright.

“WHO ARE YOU, AND WHAT BUSINESS HAVE YOU WITH MY LADY?”

The intruder yelped, and Eibhlin heard a sharp clang and another cry of distress as whoever it was scrambled to gather whatever had been dropped. There was nothing for Eibhlin to use as a weapon in the room, and her satchel was on the other side of the bed, but she crept around the foot of the bed. She made out bare feet and a habit that looked black in the lack of light, and as she came around the last corner, there was a monk cleaning what looked like liquid off the floor with his habit. Beside him, Eibhlin could just make out a dented lamp.

Taking a breath, Eibhlin stood and hissed, “Who are you? What do you think you’re doing, sneaking into my room? If you don’t answer immediately, I’ll call Father Ormulf and—”

“No! No, miss, you mustn’t call him! Kick me or beat me or curse me, but for your own sake, don’t yell or call for anyone!”

“Who are you?” Eibhlin demanded, though she kept her voice quiet.

“It’s Brother Callum, miss,” came the answer. “We passed each other earlier, but with the abbot present, I couldn’t speak with you.”

“So you snuck into a young woman’s room? Not exactly proper for a monk.”

“Who’s that?” the monk whispered, looking around the room.

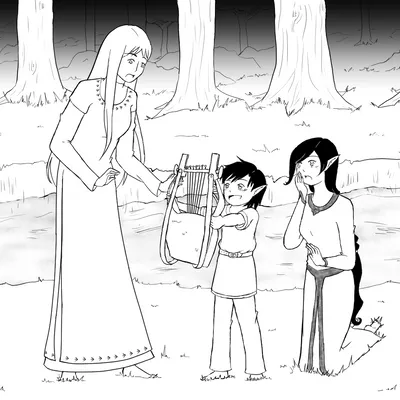

Eibhlin said, “That’s my kithara, Mel. It’s enchanted.”

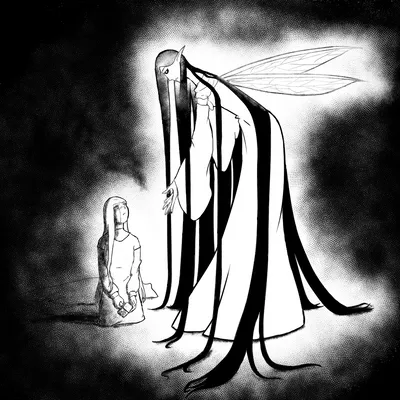

Callum moved toward the instrument and stared. “You mean this strange harp speaks?”

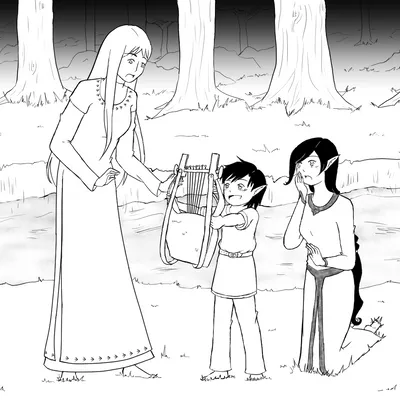

“Kithara, sir monk, but yes, I do speak,” said Mel. “I am an instrument of immeasurable quality, the eldest existing instrument, crafted a mere thousand years after the Dawn of Time. My maker was Chimelim, greatest craftsman among all races, all nations, and all ages, and I am his fourth child. I am Melaioni, Carrier and Protector of Understanding, Messenger of History.”

The monk’s tone turned respectful. “Ah! A work of Chimelim! I apologize; I didn’t recognize you. Oh dear! Now you really must leave immediately. If he realized you’re enchanted, good instrument, he’ll sell you for sure to some horrible master.”