The room was circular. Along one wall stood bookshelves packed with tomes of all sizes, most gilded with gold and gems and bearing writing Eibhlin couldn’t read. Around the other walls stood tables and shelves cluttered with jewels and flasks and bottles and boxes and talismans and charms. From the ceiling, on chains of braided silver several dozens of feet long, hung bells and amulets and plants and beads, all of which shimmered along with their chains in the moonlight weaving though the shadows from round windows on the walls and circular skylights in the ceiling far above her. In the center of the room, within a circle of moonlight, stood a round table, upon which sat a book and a single, shallow dish filled to the brim with water that rippled all on its own without spilling over the side. The atmosphere swirled around the room: ancient, powerful, terrifying. Eibhlin shivered.

Suddenly, the voice came again. “Didn’t I say to come in?”

The voice came from directly above her, right where she knew the clock face to be, and she nearly stepped over the threshold, but the rein tugged at her soul, stronger now than ever. Eibhlin replied, “I would prefer to stay out here.”

“Is that so. How sad, but very well.”

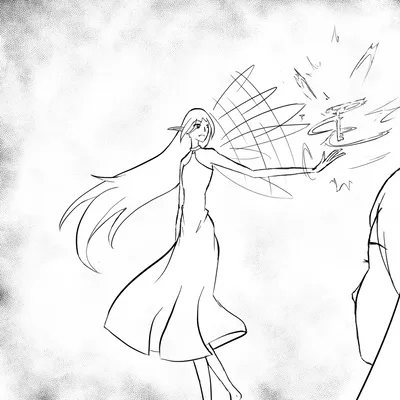

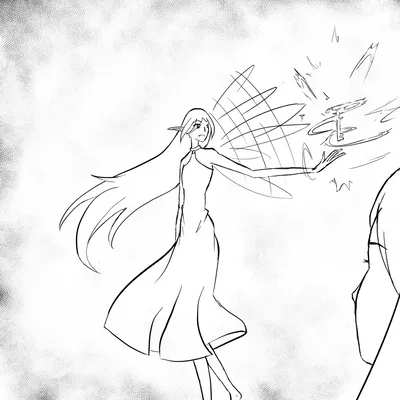

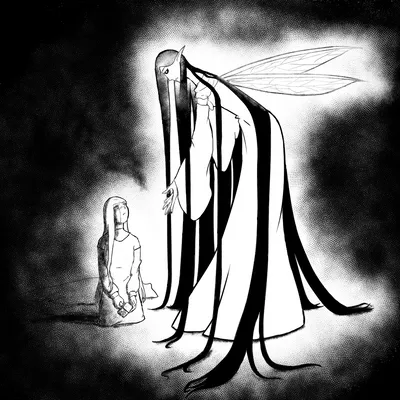

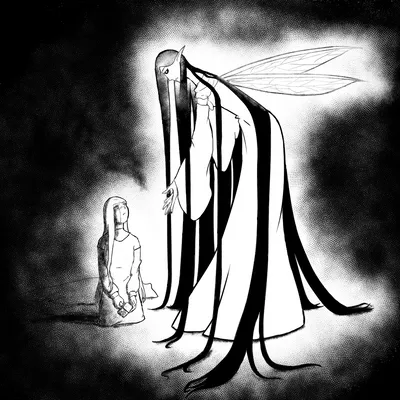

Eibhlin heard the rustle of cloth, and it seemed as though the Moon herself descended before her. The figure stood tall and slender, her arms and fingers so thin and pale they seemed as though made of the moonbeams from the gatehouse. Her hair poured down in silver threads that faded to the soft violet of the Moon above, and when she moved those colors shifted and flowed like rippling water reflecting the Celestial Queen. Nearly transparent wings peaked out from beneath the hair, twitching as though with a mind of their own. Her dress was black, like the Fae sky, but rather than generate any morbid thoughts, the color seemed to bring out the glow in her complexion. The lady’s face seemed like the missing face of the Moon, pale but not unhealthy, with large, dark eyes and a thin smile playing upon dainty lips.

Eibhlin felt as though she had never seen a more extraordinary woman. All memories of beauty fled in shame. All, that is, save one, a memory so distant it felt as though a cloud drifting somewhere in an empty sky. A gentle smile and comforting touch. Someone, no, perhaps a few people? Where had she—

“Why do you ignore me, human child? Did you not come here to speak with me?”

The Witch’s voice cut through the faint memories, scattering the forming faces. With flushed cheeks, Eibhlin focused back on the fairy. “So, you’re the Witch of Hours, Arianrhod?”

“Would you have come here if I wasn’t?” the Witch replied with laughter light as raindrops.

Drowsiness settled on Eibhlin’s eyes, much like on a cloudy or rainy day, but she shook it off. She said, “I have business with you.”

“Of course you do. No one visits me unless on business. I make sure of it.” The fairy turned and began walking around the room, her bare feet hardly making a sound. She passed among her shelves, fiddling with one thing and then another as she spoke. “And? What might you desire? What is your wish? Do you need a curse or a blight?”

“No. I need you to—”

“Or perhaps a talisman or potion? You won’t find a better sorceress in that field than I. I made sure of it.”

“No. I want—”

“Or…” said the Witch, striding over to her center table and running her fingers around the rim of the bowl, “perhaps you wish to see the future? I can show you a future with absolute certainty, bind you to it even, unlike those ‘provisional’ prophecies of those weak elves and my fellow fae. Or perhaps a love divination? Young girls like you, always searching and hoping for romance.”

“I’m not here for a love divination. I—”

“No. No, not the future. You seek a deeper, more powerful magic.” Here the lady’s voice sank into a tone so sweet Eibhlin could not speak. “No,” whispered the Witch, drawing her finger across the water in the bowl. “No. You seek something else. Distant and ever growing farther. A distant happiness long lost. If only. If only. Echoes of days and joy and love, all gone, all lost.”

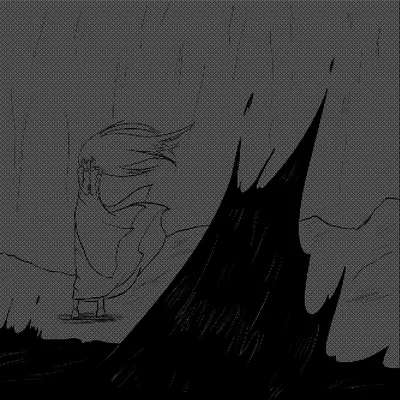

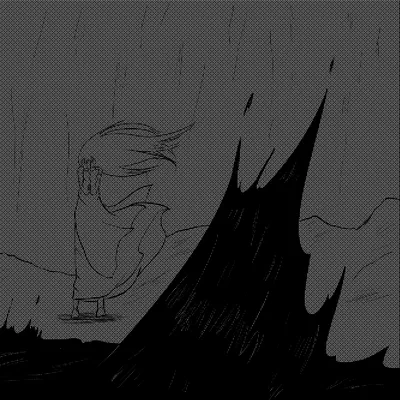

At those words, Arianrhod lifted her fingers, letting the water drip back into the dish like sand in an hourglass. Then she turned and began gliding toward Eibhlin, her voice gentle, soft as snowflakes. “Yes. All lost. All gone. Such happiness you could have had, such sorrow you have endured. Looking at you, I almost weep. To think, if not for one event or one choice or one moment, you would never have had to suffer. It would never have happened; you would have been so happy. Poor child. Pitiful child. Poor, pitiful Eibhlin.”

Now, the fairy stood before Eibhlin, arms outstretched as though to cup the girl’s face in her hands, and Eibhlin stood frozen until that last word made her twitch. “My name,” murmured Eibhlin, some of her awareness returning, her mind slowly trudging through its sluggishness as she spoke. “My name. How do you know my name?”

The fairy’s hands stiffened and then drew back as she gave a slight laugh. “‘How’ you ask? Poor child, pitiful Eibhlin, of course I know. I know all about you. I know about the struggles you’ve faced in coming to me, and the dangers you’ve met since you left home. I know of your kind but absent father, and your anger and sadness and guilt. Oh yes, guilt. Guilt at being angry. Guilt over your jealousy for his kindness. And I know the reason for all of it. I know about the lovely woman with sun-kissed hair and warm hands and smiles. I know about the love she gave to you and your father, and the devotion and adoration he held for her. And I know the anguish he felt as he watched her slowly die. Such a dreadful illness. Yet unnamed, without known cure. Treatment after treatment. Much too expensive for a small-town blacksmith, even when the village pools its money. Too expensive. No hope. Yes, Eibhlin, poor child, I know all about you, even about that tragedy that you forgot.”