Eibhlin stared at the tower.

“Maybe the trees grew restless knowing we were so close to their master’s home,” said Melaioni. “Or perhaps that it was taking us so long to reach it.”

“How could I have missed something so huge?” Eibhlin asked.

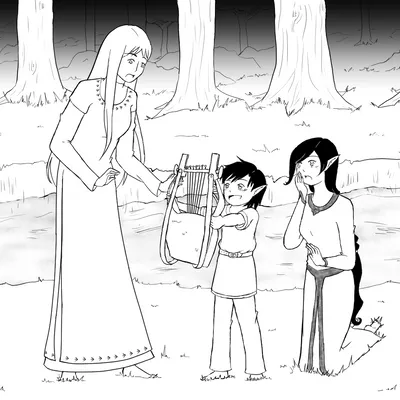

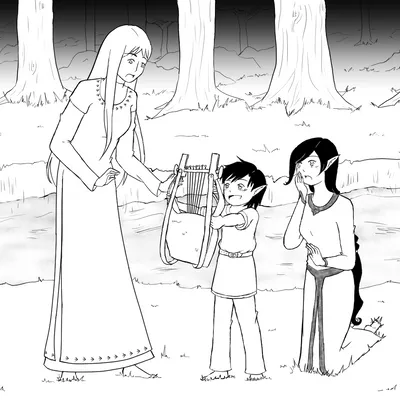

The kithara’s strings creaked with tension. “Because, Milady, this is an enchanted space. Look around the edge. Do you not see that all the trees are Tensilkir? They are forming a barrier around this place.”

“So we’re inside the barrier. But now what?”

“That is for you to decide, Milady.”

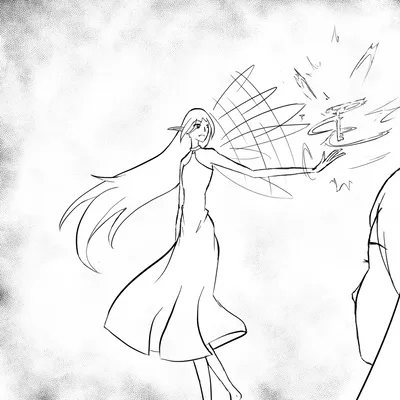

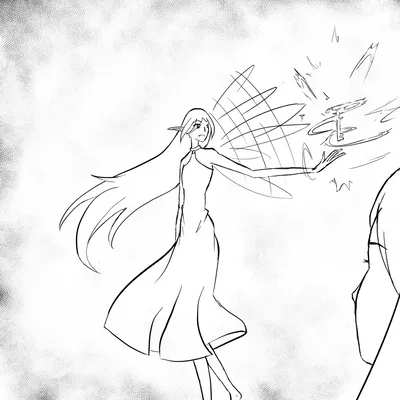

Eibhlin looked back at the forest. A shiver ran through the trees. The trees frightened her, but the tower terrified her. But what did that matter? What did any of it matter? Had she not come here for a reason? Had she not faced that swamp, those woods, and all her previous trials for some purpose, a purpose that had led her here?

“But for what?” Eibhlin whispered.

“Did you speak, Milady?”

“No. No, it’s nothing.” Or so she said. Inside, Eibhlin’s heart pounded. Why had she come here? Somehow, she couldn’t quite remember. There was something, something about her father. No, a key? Yes. It was a key. But what—

“Milady?”

“What? Oh, yes. Well, to go back now would be pointless, wouldn’t it? I can’t turn back now, Mel, not after everything I’ve been through.”

Eibhlin felt a pulsing sting in her right hand that hadn’t left since she had cut the branches and her hair. She looked down. Welts and blisters covered where the tree sap had landed on her hand, and the cuff of her sleeve looked burnt. Beneath the holes in her sleeve, more stinging red spots dotted her arm. The pain throbbed up her arm, much like the time she had burned herself in her father’s forge. Next, she reached up to where her hair had been. The tips crumbled to soot, and what remained of her hair was no more than chin-length, caked in mud and mire, and ragged as a cat after a rain storm. Her hair. Her hand. The scrapes and bruises. Dark elves and fae creatures and attempted kidnapping. The swamp and its clawing trees. No. Too much. She had endured too much to turn back now.

“We’ll go in. We’ll speak with Arianrhod,” she said, the pain in her hand strengthening her will.

“Very well, Milady. I am but an instrument. I go where you take me,” said Mel.

Eibhlin picked up and shouldered the kithara and her bag. She searched around till she found the iron penknife lying spotless in the grass save for some new burn marks on the bone handle. When she was sure she had everything, besides the cloak she had left be-hind at the tree, she turned toward the tower.

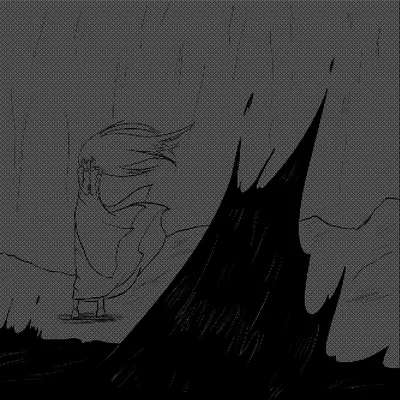

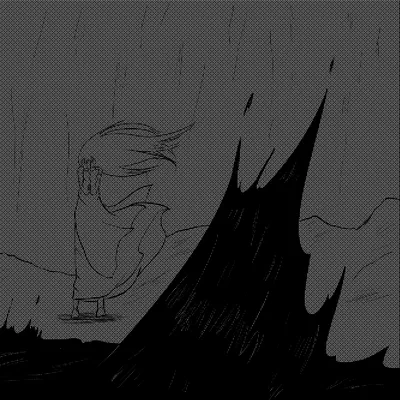

It stood like a slab of solid moonlight. Upon the clock face, neither of the hands moved; they remained forever frozen on a minute to twelve. Noon. Or perhaps midnight, the time of broken spells, a time never to come upon that tower. Just below the clock face, a walkway led from the tower down to a small gatehouse, forming a joint structure that reminded Eibhlin of a sundial. One without a shadow. A useless sundial.

There was no gate or doorway to the larger tower save the one beneath the clock face, so Eibhlin approached the gatehouse. To reach it, she had to cross the shallow stream circling the tower, water moving, she assumed, by magic. In any case, there was no choice but to cross it.

As she waded through the shin-deep moat, Mel said, “Milady, before you go farther, I need to tell you something.”

Eibhlin stopped, and the moving water chilled around her legs, giving her a strong desire to hurry across the rest of the way, but she stood still. “What is it, Mel?”

“I have told you of my last visit, or series of visits, to this place and the sorrowful end to my master at that time. There is something else I think you should know.

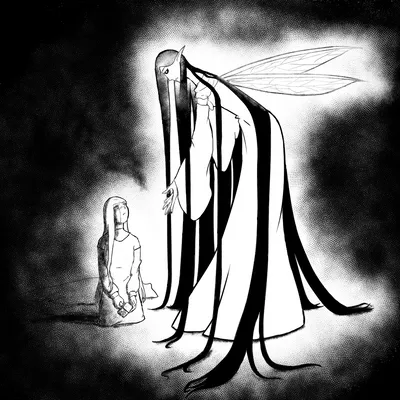

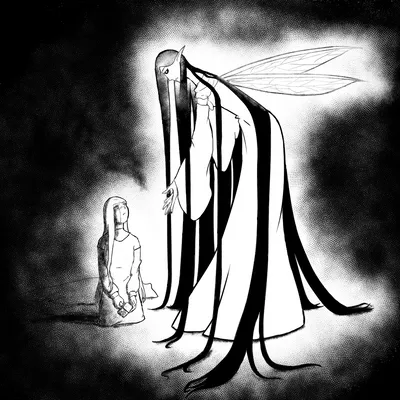

“As soon as one knocks upon that door, no, perhaps the moment one enters this swamp, the witch’s enchantments begin to work upon a person. It is an ancient, natural magic that crossing thresholds signifies crossing deeper into another’s domain, placing one’s self under another’s power, and the deeper we go, the stronger Arianrhod’s influence. This stream is one such threshold, for running water has been an especially strong boundary line since the beginning of time, and from here on, the more you cross the more you shall fall under Arianrhod’s hold. For instance, there is a dreadful spell in this place that makes your reason sluggish. For another, I might become unable to speak with you. Such occurred last time I was here. Enchanted I may be, and unable to be overcome with emotions, but magic is entirely different.

“And so, I shall tell you this now, before the spells become too thick: be wary of crossing thresholds, and do not, under any circumstances, cross the threshold into the room where the Witch is. So long as you stay outside that room, a layer of the Witch’s magic cannot reach you, and her control over you is weaker. Do you understand me, Eibhlin?”

“Yes, I’ll try to remember,” she said, though even as the words left her mouth, her currently muddy memory made her uneasy.

The kithara said, “No, no. You mustn’t ‘try.’ This is something you simply ‘must.’ Now promise me you shall remember.”

“Okay. I promise,” she said. By now, Eibhlin’s legs felt like ice as the water lashed against and around her legs, but she waited for Mel to continue.

“Good. Now one more thing, and this is another thing you must promise me. Promise me by the elven blessing upon your hands and brow, swear that you absolutely, no matter what the Witch tells you, will not attempt to change the past.”

“What?” Eibhlin asked. Until Mel mentioned the idea, Eibhlin hadn’t even considered it. “Why are you talking about that?”