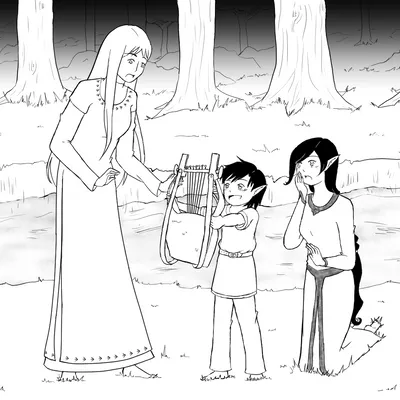

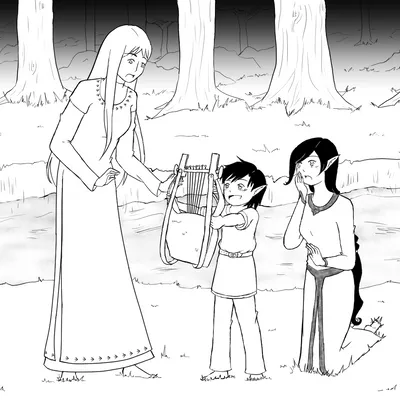

The sharp clatter of dishes came from the kitchen. Eibhlin sat in the main sitting room, the kithara lying on the table next to her. As soon as they had returned home, Shira told her mother of the events. Yashul left dinner preparations half-done, charging her children to watch the house while she and their father were gone. Since then, a couple hours had passed, and still no news had come.

Staring at the kitchen, Eibhlin murmured, “Even with the danger, they still leave their children alone.”

The kithara spoke, giving Eibhlin a shock. While lost in her own thoughts, she had forgotten about the instrument’s enchanted nature. “You need not worry,” it said. “There is strong magic within the walls and windows of this house. Only highly skilled sorcerers could break through, and the dark elves are not likely to waste such a scarce resource on a mere civilian’s home, not with armed warriors attacking their troops. Do not be so afraid.”

“I see. Thank you. I feel a bit better now,” said Eibhlin, though her face did not show it. After a moment, she said, “Kithara, what are you?”

“I am an instrument.”

“Instruments don’t talk.”

“No. Most of us do not.”

“Then why can you?”

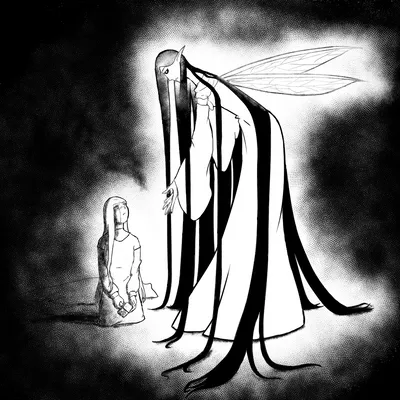

“Ah,” said the kithara, “now we reach a useful question. I possess speech because I am an instrument of priceless quality, the eldest instrument still played, crafted a mere thousand years after the Dawn of Time itself. My maker was Chimelim, greatest craftsman among all races and ages, and I am his fourth child. I am Melaioni, Protector of Understand-ing, Messenger of History.”

“Liar,” Eibhlin said flatly.

“My good lady,” cried the kithara, “you doubt my words?”

Eibhlin replied, “You can’t be telling the truth. To find someone… something as amazing as you claim to be, and in the way we did, it’s too crazy to believe. It would be too much of a coincidence.”

“Coincidence? You think our meeting just coincidence? Good lady, as said before, I am the Messenger of History. I have witnessed kingdoms rise and fall and ages pass from one to the next. If I have learned nothing else, it is that there is no such thing as mere coincidence,” said the kithara.

“But—”

“You think it coincidence that my master and I were waylaid by dark elves that likely now come to attack this town?” continued the kithara. “You think it coincidence that I fell into the river and so traveled here in time to give the elves warning? Do not call such threads coincidence. If you doubt in Divine Providence, call them fate or the work of Lady Fortune, if you must. Only do not call them coincidence. That is but a dream.” After Eibhlin gave no reply, the kithara asked, “Have I cleared your mind, good lady?”

“No,” she said.

“I see. I am sorry, then, if my words brought only confusion. Have I at least cleared my name? You still think me a liar?”

“I’m not sure,” replied Eibhlin. “I think I want to believe you, though.”

“If you need sure evidence, the elf daughter can confirm the truth of my claim,” it said.

“No. I’ll believe you.”

“You no longer think me a liar?”

“I don’t,” said Eibhlin.

A soft sigh, like the lightest thrum of its strings, came from the kithara. “Thank you, my most gracious lady. As the Messenger, to be accused of twisting truth, such a charge near splintered me.”

Eibhlin blushed. “I-I didn’t—”

“No, no, my good lady. Do not hesitate to speak your mind to me. Honest thoughts matter more to me than kindness, even when painful,” said the kithara.

Eibhlin said nothing, but she felt a bit relieved and let her shoulders relax.

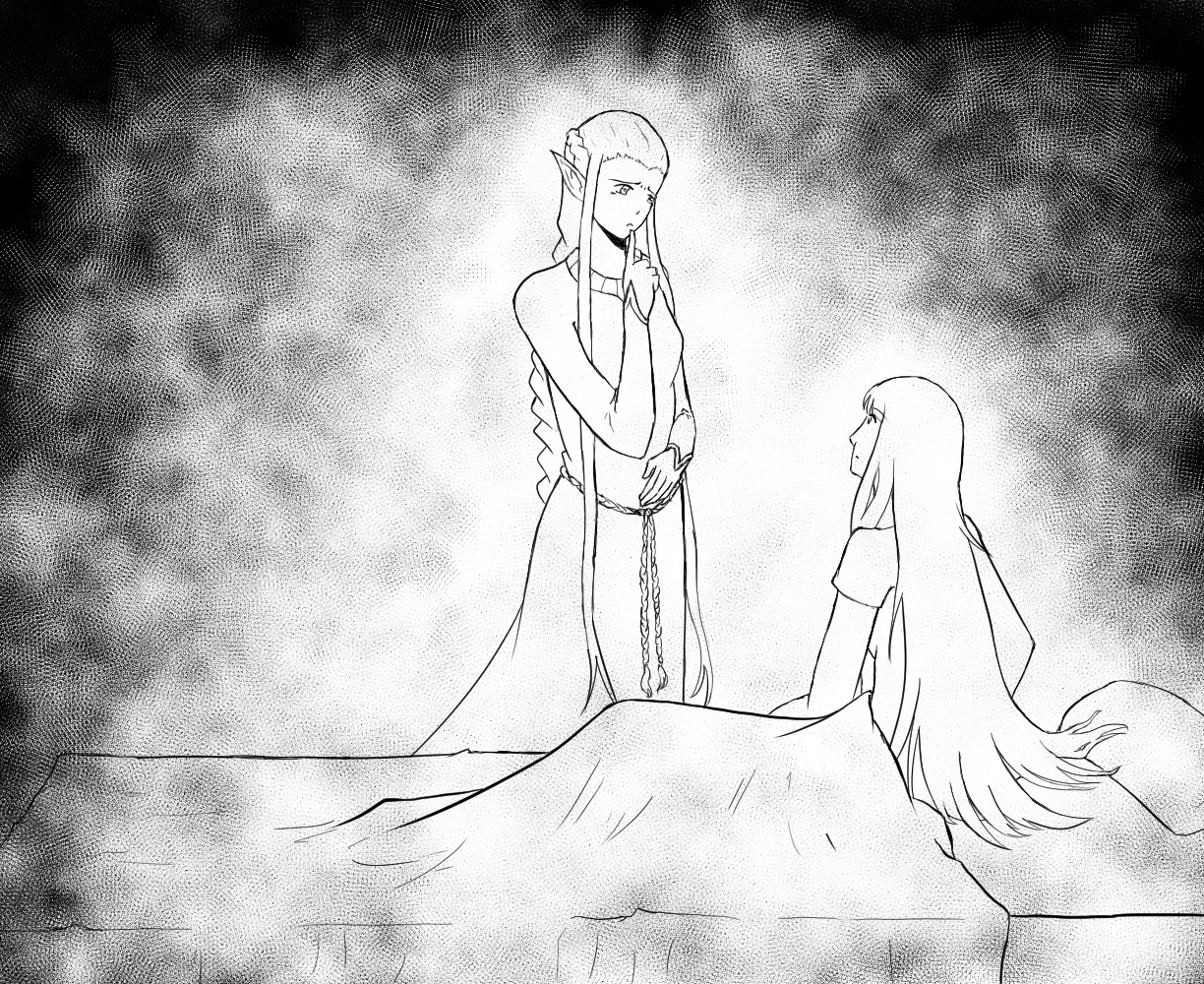

Late afternoon shifted to evening, and evening to night. There was no moon. During that time, Elkir had come into the sitting room, shooed from the kitchen by his sister, and sat down next to Eibhlin. He turned through a book, but Eibhlin could tell his mind didn’t really process a single word. The kitchen had long gone quiet, but there was no peace in that quiet.

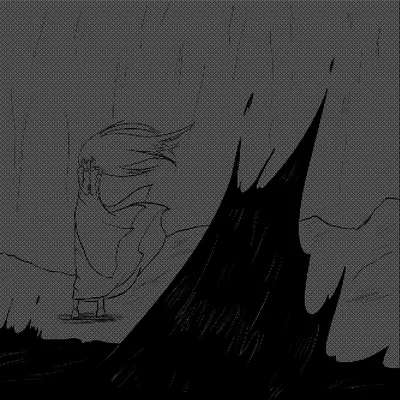

Everything shattered with the crashing of glass. The sound filled the house, swallowing all others. It had come from the bath.

In her fright, Eibhlin couldn’t even scream. Beside her, Elkir whimpered. He seemed about to cry when Melaioni hissed, “Quiet!” Just that one word, but with it came terror. Elkir grabbed Eibhlin’s kirtle. Eibhlin’s own hands locked into fists on her lap. Both stared, unmoving, in the direction of the bath.

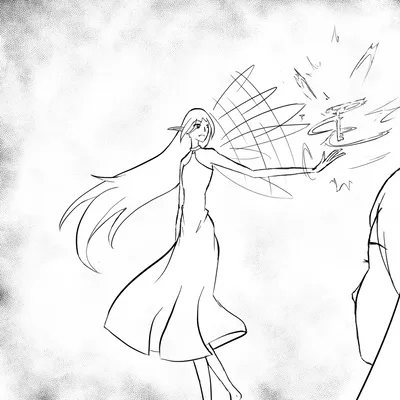

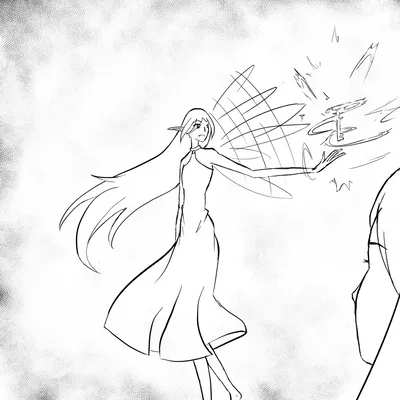

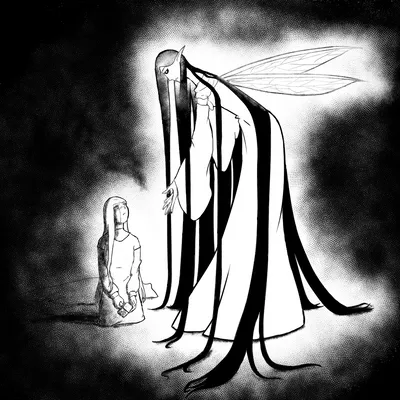

So focused and tense was she that Eibhlin barely bit back a cry when Shira appeared and touched her shoulder. Eibhlin almost spoke, but the elf’s trembling hand motioned for silence. Shira lifted the kithara from the table and snuck into the hall toward the guest room, beckoning for the others to follow. Slipping off the couch, Eibhlin followed as quickly as she dared, Elkir still gripping her kirtle. The group slid into the guest room. Shira took out a key and locked the door, muttering a few words. A dim glow spread over the door before fading into the wood.

“That should give us some protection,” she said.

“What’s going on?” asked Eibhlin.

“Dark elves,” said the kithara with a voice like a dissonant chord. “I would know this feeling anywhere, sends my strings trembling.”

“I thought you said they can’t get in here!” said Eibhlin.

“They shouldn’t have. I don’t know how—” Melaioni broke off.