Chapter Three: A Scolaris Gestos IV

Dawn found me still wakeful, my mind churning with possibilities. I rose and prepared for the day, moving through the familiar routine of washing, dressing, and proceeding to the church for matins. This time, I was careful to appear attentive throughout the office, aware now that several pairs of eyes might be monitoring my behavior.

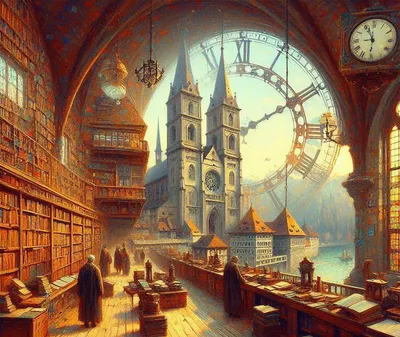

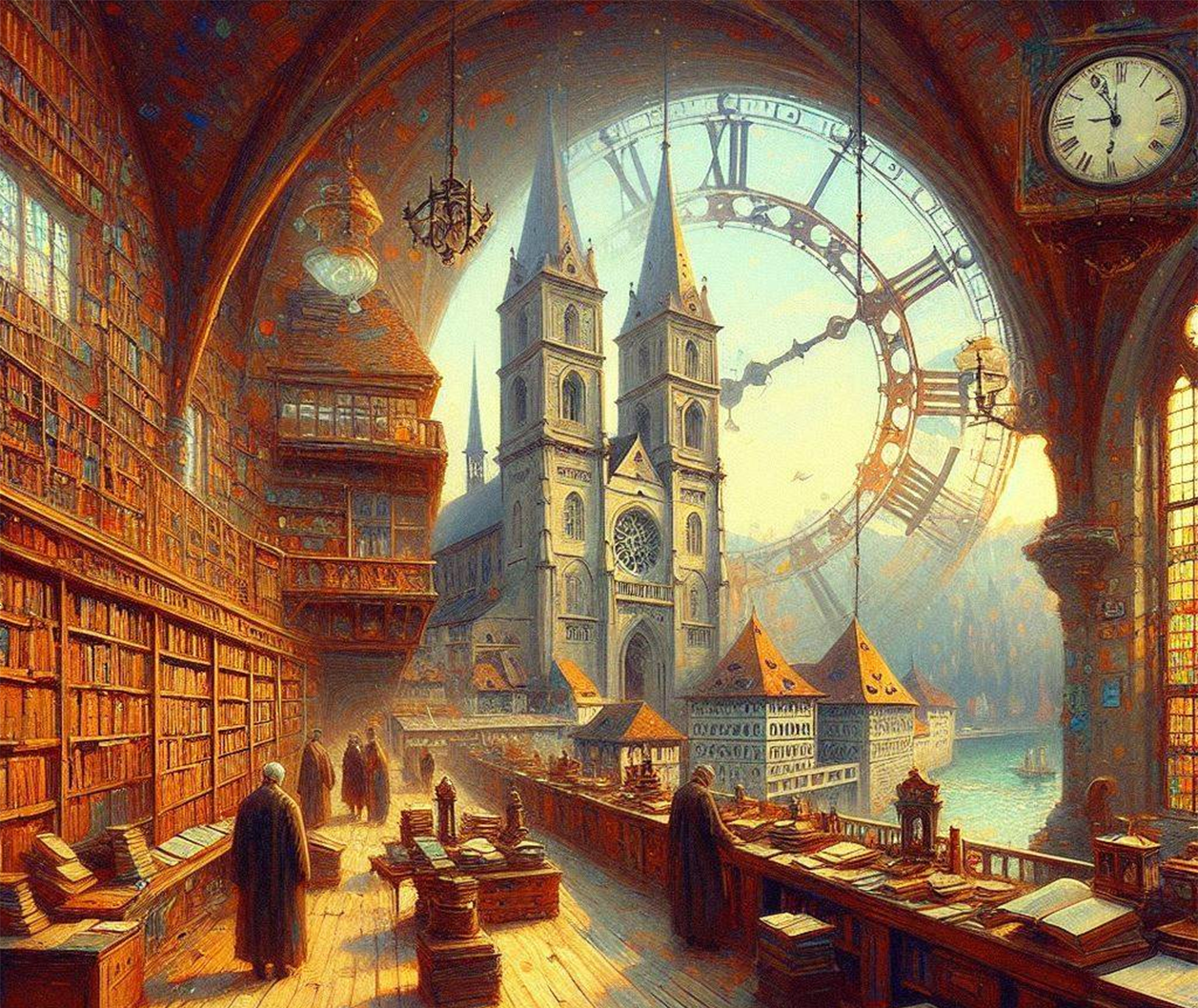

After breakfast—a simple affair of bread, cheese, and weak ale—I made my way to Brother Clemens's observatory, a small stone structure perched on the abbey's western wall, offering an unobstructed view of the heavens. He was already there, amid his astrolabes, armillary spheres, and carefully drawn charts.

"Ah, Brother Lukas," he greeted me, setting aside the instrument he had been adjusting. "Come in, come in."

I entered, noting with interest the complex mechanisms that surrounded us—some of Brother Clemens's own design, others reproductions of devices described in ancient texts. The walls were covered with calculations, star charts, and tables of celestial movements.

"You have a remarkable collection," I said, genuine admiration in my voice.

"The fruits of a lifetime's study," he acknowledged. "Now, you were interested in astronomical events of the eighth and ninth centuries, were you not?"

"Yes." I moved closer, examining a detailed chart of lunar eclipses. "Particularly any events that might help corroborate or date certain documents from Reichenau."

He nodded and pulled a large folio from a shelf. "This contains my calculations of all significant celestial events visible from this region, from the time of Christ to the present day. Eclipses, comets, planetary conjunctions—all plotted according to the best mathematical models."

He opened the volume, revealing page after page of meticulous calculations, diagrams, and tables. "What specific period interests you most?"

"Let us say, from 650 to 950," I replied, deliberately encompassing the entire span of the alleged phantom centuries and some time on either side.

Brother Clemens ran a finger down an index, then turned to a section near the middle of the book. "Here we are. You'll note that observations become somewhat sparse during the seventh and eighth centuries—the so-called Dark Ages were dark for astronomy as well as other sciences."

I leaned closer, studying the entries. Indeed, between approximately 650 and 750, the records were less detailed, with many events marked as "calculated" rather than "observed." This in itself was not suspicious—the political and social upheavals of the period could easily explain a gap in systematic observation.

But then I noticed something odd. Starting around 750, coinciding with the rise of Charlemagne according to conventional history, the records became suddenly more complete and precise. Too complete, perhaps, given the supposed technological and scholarly limitations of the time.

"These observations from the late eighth century," I said, trying to keep my voice casual, "they seem remarkably detailed. Were there particularly skilled astronomers active at that time?"

Brother Clemens hesitated, his finger hovering over a diagram of a solar eclipse supposedly observed in 787. "That... is an interesting question, Brother Lukas. The traditional narrative attributes these observations to the scholars gathered at Charlemagne's court—men like Alcuin of York and Rabanus Maurus."

"But?"

He glanced at me, then back at the chart. "But there are certain... inconsistencies in the data. Discrepancies between what these observations claim and what modern calculations suggest should have been visible."

My heart quickened. "What kind of discrepancies?"

Brother Clemens closed the book suddenly, his expression troubled. "I misspoke. The records are consistent with what we would expect, given the instruments available at the time."

But I had seen the doubt in his eyes, the momentary crack in his scholarly composure. "Brother Clemens," I said softly, "if you have noticed anomalies in the astronomical record, surely that is a matter worthy of investigation?"

"Some anomalies," he replied, not meeting my gaze, "are best left unexplained, Brother Lukas. As the ancient philosopher Empedocles wrote, 'Blessed is he who has acquired a wealth of divine wisdom, but miserable he in whom there is a dim opinion concerning the gods.' Some questions lead us not toward divine wisdom, but into miserable uncertainty."

"Or toward uncomfortable truths," I suggested.

He looked at me then, his eyes sharp despite his age. "I have heard that Father Umbertus discovered you with a certain book. A book bearing a quartered circle on its binding."

I stiffened. "You know of this symbol?"

"I know that it represents danger, Brother Lukas. Not physical danger—though that may come as well—but the danger of knowledge that unmoors us from our place in God's creation."

"Veritas nunquam perit," I quoted. "Truth never perishes."

"No," he agreed, "but those who pursue it too ardently might." He sighed, suddenly looking every one of his seventy-some years. "I was like you once, you know. Full of questions, unwilling to accept limitations on my inquiry. I, too, noticed certain... peculiarities in the historical record."

"What did you find?" I asked, holding my breath.

He was silent for a long moment, as if weighing decades of caution against the relief of finally speaking openly. "Enough to understand that some doors should remain closed," he said finally. "Enough to recognize that the order of our world—our faith, our institutions, our very understanding of who we are—rests upon foundations that might not bear too close an examination."

"But if those foundations are false—"

"What would you put in their place?" he challenged. "Chaos? Uncertainty? A world where nothing can be trusted, where three centuries might vanish at the stroke of a scholar's pen?" He placed a gnarled hand on my arm. "Listen to me, Brother Lukas. I have walked the path you are now treading. It leads to a precipice, not a revelation."

"Or perhaps beyond the precipice lies a truth we have been afraid to face," I countered.

He shook his head sadly. "You will not be dissuaded, I see. Very well."