Chapter Three: A Scolaris Gestos III

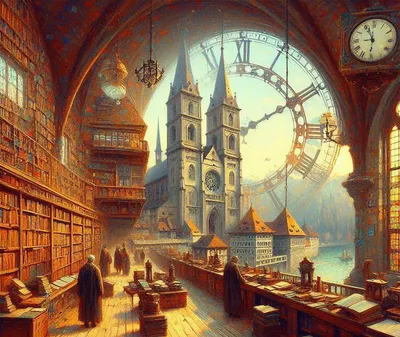

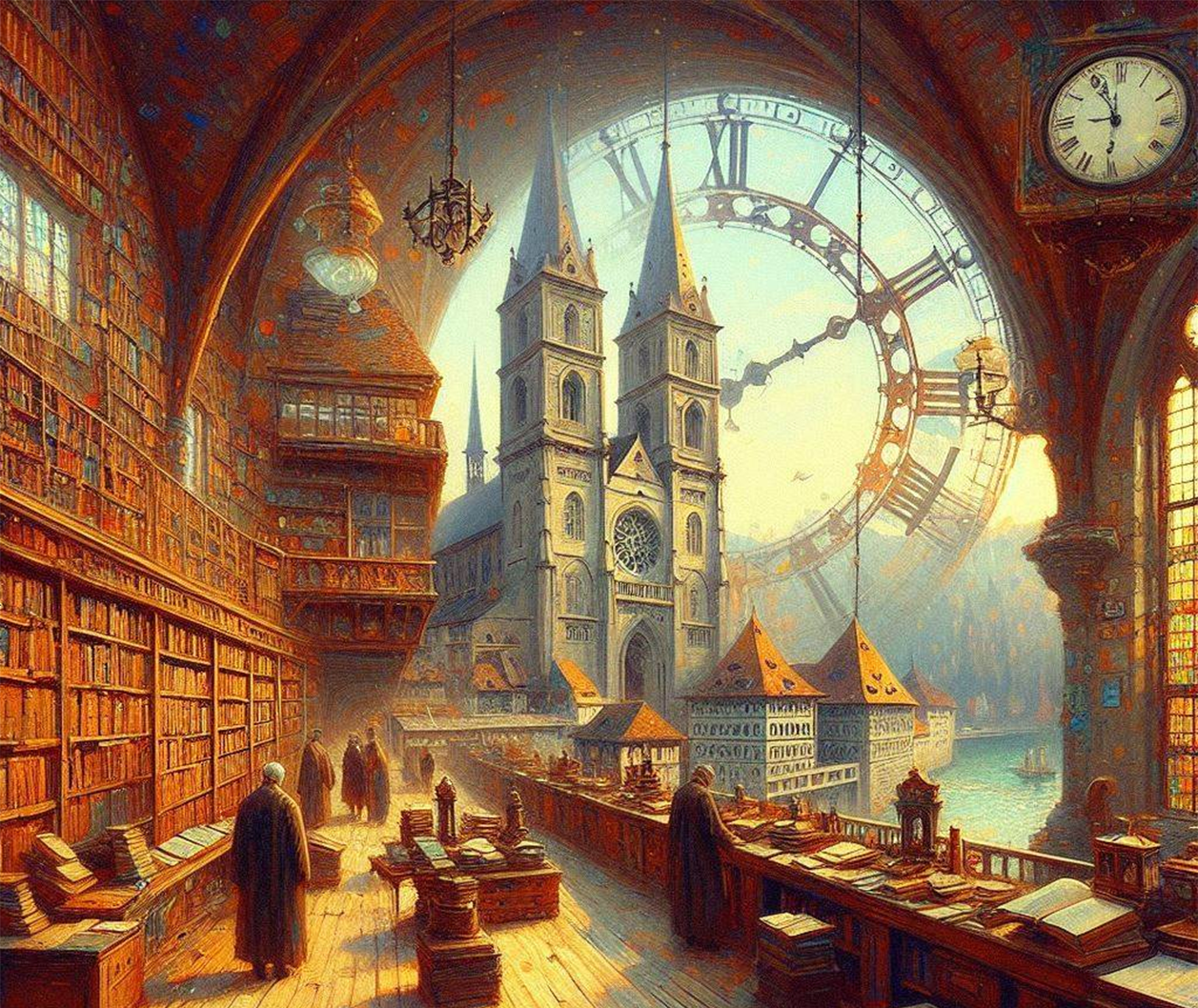

I returned to the scriptorium to find Brother Adelbert already there, unpacking another crate of manuscripts.

"The abbot spoke with you," he said, not looking up from his work.

"News travels quickly within these walls."

"Only certain kinds of news." He glanced at me, then away. "He is concerned for you. As are we all."

"And what exactly is it that concerns you, Brother Adelbert?" I asked, moving to help him with a particularly large codex. "What terrible fate do you imagine awaits me if I continue my research?"

He hesitated, his hands stilling on the manuscript. "There are stories," he said finally, his voice barely above a whisper, "of scholars who delved too deeply into certain matters. Men who asked questions that... disturbed the order of things."

"And what happened to these men?"

Adelbert shrugged, a small, nervous gesture. "They disappeared. Or they went mad. Or they recanted suddenly, becoming the most ardent defenders of the very ideas they had questioned."

"These sound like tales meant to frighten novices," I said, though a chill ran through me at his words.

"Perhaps." He turned his attention back to the crate. "But Father Umbertus is not a man given to superstition or idle threats. If he warns you away from a path, Brother Lukas, it is because he has seen where it leads."

I considered pressing him further, but we were interrupted by the arrival of two novices, sent to assist with the heavier work of moving and arranging the manuscripts. The moment for confidences had passed.

Throughout the afternoon, I continued my examination of the Reichenau documents, now with Brother Adelbert as my ever-present shadow. His presence limited my ability to take notes on my observations, but it could not prevent me from seeing what was increasingly obvious: the documents from the contested centuries had a quality of artifice about them, a consistency that spoke not of organic historical development but of careful, retrospective construction.

By vespers, I had formulated a plan. I would need access to astronomical records—calculations of eclipses, planetary conjunctions, and other celestial events that could be verified against modern observations. If the chronology had indeed been manipulated, such calculations would reveal the discrepancies.

After the evening meal, taken in silence as was our custom, I approached Brother Clemens, the abbey's astronomer and mathematician.

"Brother Clemens," I began, as we walked together toward the dormitory, "I find myself in need of your expertise."

The old monk raised his bushy eyebrows. "Indeed? How might I assist you, Brother Lukas?"

"I am examining some documents from Reichenau that make reference to astronomical events—eclipses, comets, unusual conjunctions. I wonder if you might have records that would help me date these phenomena precisely."

"Ah," he nodded, his eyes brightening with scholarly interest. "Yes, of course. Astronomy is the clockwork of history, is it not? Coeli enarrant gloriam Dei, as the Psalmist says."

"The heavens declare the glory of God," I translated automatically. "And in this case, perhaps they might declare something about our understanding of the past as well."

He gave me a curious look. "An intriguing way to phrase it. What period are you researching?"

"The eighth and ninth centuries," I said, watching his reaction carefully. "Particularly the reigns of the later Merovingians and early Carolingians."

Something flickered in his eyes—recognition? concern?—but he merely nodded. "I have some tables that might be of use to you. Calculations of eclipses visible from this region, recorded appearances of Halley's Comet, and so forth. They are in my observatory. Shall we say tomorrow, after the morning office?"

"That would be most helpful," I said, trying to contain my excitement. "Thank you, Brother Clemens."

"It is my pleasure to assist a fellow scholar." He paused, then added, seemingly as an afterthought, "Father Umbertus mentioned you have been... pursuing some unusual lines of inquiry of late."

So, Umbertus had spoken to Clemens as well. How many other brothers had been enlisted to monitor me?

"I follow where the documents lead," I said simply. "Is that not our duty as custodians of knowledge?"

"Indeed." He nodded slowly. "But sometimes, Brother Lukas, the documents lead us into territories best left unexplored. As Aristotle warned in his Metaphysics, 'The investigation of truth is in one way hard, in another easy.' The difficulty lies not in finding paths but in choosing wisely among them."

"I will remember your counsel," I said, bowing slightly as we reached the dormitory door.

"See that you do." His tone was gentler than Umbertus's had been, but the warning was no less clear. "Good night, Brother Lukas."

"Good night, Brother Clemens. Lux in tenebris lucet."

"Et tenebrae eam non comprehenderunt," he finished the quotation automatically. "The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not comprehended it."

I watched him shuffle away, wondering if he understood the significance of the exchange. If the accepted chronology was indeed a fabrication—a darkness imposed upon the light of truth—then my investigation might be the first gleam of illumination in centuries.

That night, in the secrecy of my cell, I added the day's observations to my hidden journal. I noted Brother Clemens's reaction, subtle though it had been, to my mention of the eighth and ninth centuries. I recorded the peculiarities I had observed in the Reichenau documents—the too-perfect script, the odd disconnection in the correspondence, the absence of authenticating details.

And I posed questions that now haunted me: If three centuries had been inserted into history, how had the deception been maintained? Who had orchestrated it, and to what end? And most troubling of all, who were "those who claim to be the guardians of true time," as Father Umbertus had called them?

Sleep eluded me, as it had for nights now. I lay on my pallet, staring up at the rough-hewn beams of the ceiling, tracing patterns in the wood that seemed, in my fatigued imagination, to form the quartered circle I had seen on the forbidden book.

"Historia est magistra vitae," I whispered into the darkness, quoting Cicero. "History is the teacher of life." But what if the history we knew was a lie? What lessons then could we draw from it?