Chapter Four: Defectus Eclipsus II

Outside, in the relative safety of the corridor, I allowed myself a moment of trembling relief. The encounter had been a warning, clearly, but also a revelation. The "guardians of true time" were not some shadowy local conspiracy but reached to the highest levels of the Vatican itself. And they were concerned enough about what I might discover to send an emissary to monitor my progress.

I clutched Visconti's astronomical reference to my chest, wondering if it was a genuine resource or a carefully constructed tool of misdirection. Either way, it would be valuable—if the calculations were accurate, they would help me identify discrepancies; if falsified, they would reveal the very deception I sought to uncover.

Instead of returning to the scriptorium, I made my way to Brother Clemens's observatory. The old astronomer was not there, but I knew he would not mind my use of his sanctuary. I needed solitude, quiet, and access to his own astronomical calculations to compare with Visconti's gift.

I retrieved Brother Clemens's green manuscript from its hiding place and brought it to the observatory. There, with the dome's small windows admitting the late afternoon light, I spread both books before me and began my comparison.

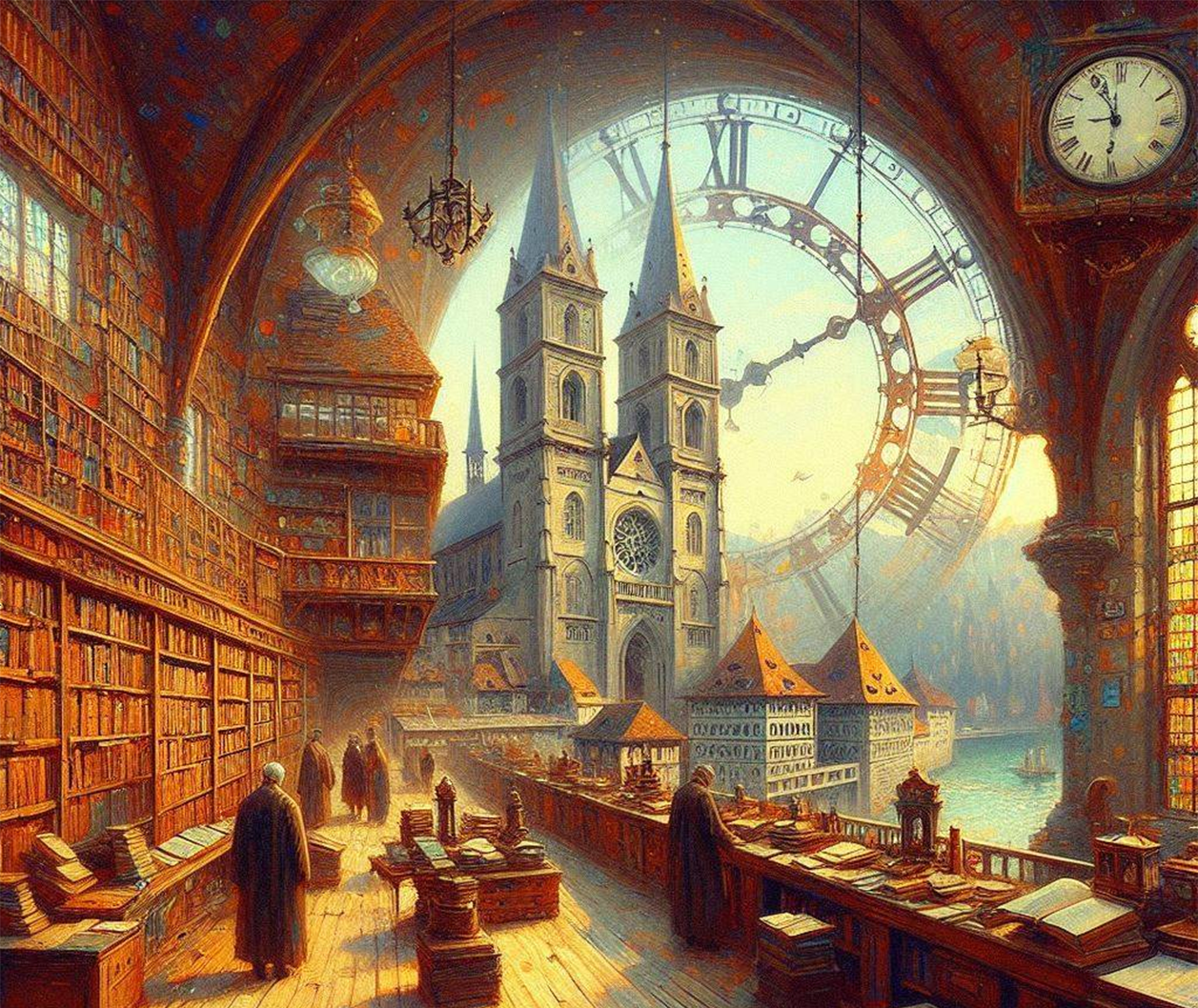

Visconti's volume was meticulous, showing not just the dates of celestial events but their visibility from various European locations, their duration, and their angular measurements in the sky. Brother Clemens's private calculations were less formal but contained detailed notes on his sources and methods, along with expressions of doubt where his calculations contradicted accepted historical accounts.

For the first hour, I found nothing immediately suspicious. The dates for lunar and solar eclipses matched between the two sources, as did records of comets and planetary conjunctions. But as I delved deeper, focusing on the period between 650 and 950 AD—the alleged phantom centuries—discrepancies began to emerge.

According to Clemens's calculations, a total solar eclipse should have been visible from Constantinople in July of 775 AD. The historical records indeed mentioned such an eclipse, with Byzantine chronicles describing how "the day was turned to night" during the reign of Emperor Constantine V. Yet Visconti's reference placed this eclipse in 774, not 775, and calculated it as only partial in Constantinople.

A minor discrepancy, perhaps—a year's difference might be attributed to calendar variations or recording errors. But as I continued my comparison, more anomalies emerged. A triple conjunction of Mars and Jupiter recorded in Frankish annals for the year 807 could not, according to Brother Clemens's calculations, have occurred as described. The planets would not have been in the correct positions.

More troubling still was an account of Halley's Comet in 684 AD. The comet's appearance is reliably periodic, returning approximately every 76 years. Brother Clemens had calculated its appearances backward through time from known modern observations. According to his work, Halley's Comet should have been visible in 684, and historical records did indeed mention a "great star with a tail" in that year.

But Clemens had added a disturbing note in the margin: "If 684 observation correct, then previous return in 608, not in documented year of 530 as claimed in Cassiodorus's chronicle. Impossible discrepancy of 78 years."

I sat back, my mind racing. If Halley's Comet had appeared in 530 and again in 684, with only 154 years between appearances instead of the expected 228, then one of two things must be true: either the comet's orbital period had changed dramatically (a physical impossibility), or the chronology between those dates had been somehow compressed or falsified.

I turned to Visconti's book, searching for his treatment of these cometary appearances. His entry for 684 acknowledged the historical record of a comet but dismissed it as "likely a misidentification of atmospheric phenomena or a different, non-periodic comet." For the year 530, he confidently identified the described celestial object as Halley's Comet.

The contradiction could not be accidental. Either Brother Clemens's calculations were wrong, or Visconti's reference contained deliberate falsifications.

I needed more evidence, and fortunately, astronomical records provided it in abundance. Solar eclipses, in particular, followed patterns that could be calculated with precision. If there had been a systematic distortion of chronology, eclipse records would reveal it.

I turned to Brother Clemens's notes on an eclipse reportedly observed in Rome in 840 AD during the papacy of Gregory IV. According to historical accounts, this eclipse had been total, causing momentary darkness at midday. But Clemens's calculations showed that no total eclipse would have been visible from Rome in that year—the nearest total eclipse visible from that location would have occurred in 829.

Again, I checked Visconti's reference. His entry confidently listed a total eclipse visible from Rome in 840, with precise details of its duration and path.

My hands were trembling now. The evidence was mounting that someone had deliberately falsified astronomical records to support a chronology that could not have existed. And if the chronology was false, then what of the events supposedly anchored to those dates? The coronation of Charlemagne in 800? The Synod of Whitby in 664? The entire sequence of Merovingian and Carolingian rulers?