Chapter Four: Defectus Eclipsus

"The heavens themselves, the planets, and this center, Observe degree, priority, and place... But when the planets, in evil mixture, to disorder wander, What plagues and what portents! What mutiny!"

—William Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida

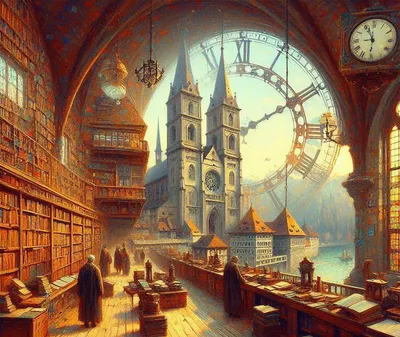

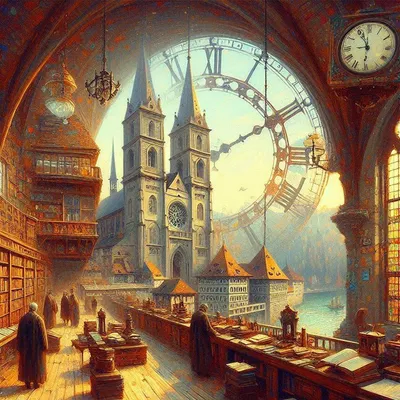

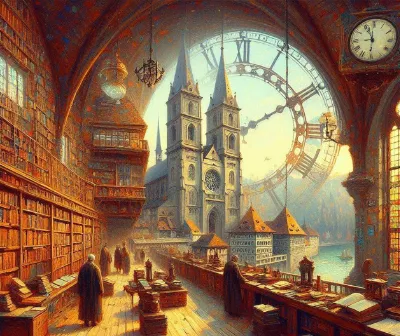

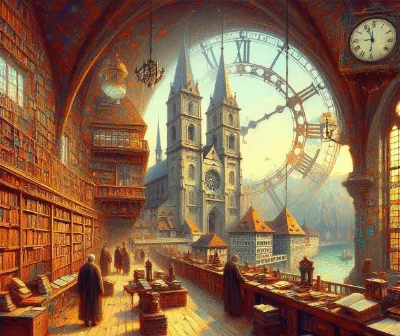

The abbot's study was illuminated by tall windows that admitted thin blades of afternoon light, slicing through dust motes that danced in their path. As I entered, I sensed the weight of authority in the room—not just ecclesiastical, but something older, more primal. Father Umbertus stood by the abbot's desk, his expression tense. Abbot Gerhardt sat behind it, fingers steepled, his face an impenetrable mask. And there, by the window, stood the stranger I had observed in the courtyard, now examining a celestial globe with affected interest.

"Brother Lukas," the abbot intoned, "may I present Doctor Alessandro Visconti, Chief Archivist of the Vatican Apostolic Library."

Visconti turned at the mention of his name, fixing me with eyes so dark they appeared almost black in the shadowed room. The ring with the quartered circle gleamed on his right hand as he offered a slight bow.

"Brother Lukas," he said, his Italian accent precise yet subtle. "I have heard much about your... scholarly endeavors."

"You honor our humble abbey with your presence, Doctor Visconti," I replied, bowing in return. "Though I confess I am surprised that my modest work cataloging manuscripts would attract the attention of the Vatican's Chief Archivist."

A smile flickered across his face, cold as winter sunlight. "The Church takes a keen interest in all scholarly pursuits, particularly those concerning the correct interpretation of historical documents."

Umbertus cleared his throat. "Doctor Visconti is conducting a survey of monastic libraries throughout Europe. He is particularly interested in any... anomalous texts that may have escaped proper cataloging."

The implication hung in the air between us. He was hunting for the forbidden manuscript—or perhaps for others like it.

"I see," I said carefully. "And how may I assist in this noble effort?"

Visconti began to pace slowly around the room, his hands clasped behind his back. "I understand you have been working with texts from the Carolingian period. Eighth and ninth-century documents from Reichenau, is that correct?"

"Yes, that is my current assignment."

"And have you noticed anything... unusual about these documents? Any inconsistencies or peculiarities that might suggest they are not what they appear to be?"

His directness startled me. I had expected circumlocution, hints, veiled threats—not this frontal assault.

"The documents appear consistent with others from the same period," I answered, choosing my words with care. "Though of course, dating manuscripts precisely is always a challenge for even the most experienced paleographer."

"Indeed." Visconti stopped his pacing directly in front of me. "Yet I am told you have been consulting with Brother Clemens about astronomical references in these texts. Might I ask what prompted this specific line of inquiry?"

My mind raced. How much did he know? How closely had I been watched?

"Several of the documents refer to celestial events—an eclipse, a comet's appearance. I thought comparing these accounts with astronomical records might help confirm their dates of composition."

"A sound methodology," Visconti conceded. "Though astronomy itself is not without its... complexities, is it? Even the great Tycho Brahe, with all his meticulous observations, found himself confounded by apparent discrepancies in the heavenly motions."

The mention of Brahe was deliberate, I was certain. The Danish astronomer's work in the 16th century had revolutionized observational astronomy, providing the data that Kepler would later use to formulate his laws of planetary motion. But what was Visconti suggesting?

"Brahe had the advantage of precise instruments," I replied. "Medieval observers were more limited in their capabilities."

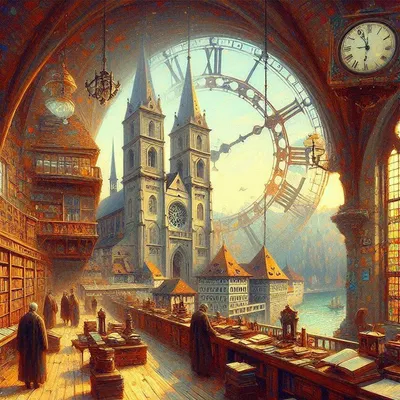

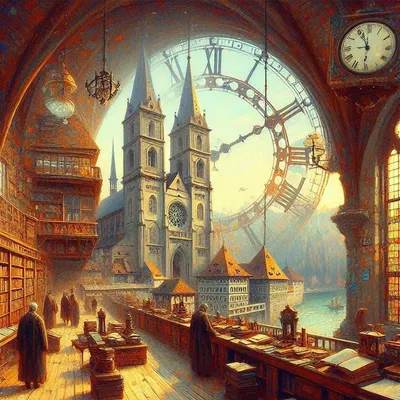

"And yet," Visconti said, "medieval astronomers left records of eclipses, planetary conjunctions, comets—records that modern science can verify or disprove with mathematical certainty." He moved back to the celestial globe, spinning it idly with one finger. "Such records are like anchors in the sea of time, Brother Lukas. They tether historical events to the immutable mathematics of celestial mechanics."

The abbot shifted uncomfortably in his chair. "I'm sure Brother Lukas understands the importance of accurate dating, Doctor Visconti. He is one of our most meticulous scholars."

"No doubt." Visconti's smile did not reach his eyes. "Which is why I am confident he would report any significant discrepancies he might discover. The Church values accuracy in all things, after all."

The threat was clear, though veiled in courtesy.

"Of course," I said, meeting his gaze steadily. "Truth is the highest aim of all scholarly endeavor."

"Truth," Visconti repeated, as if tasting the word. "A noble pursuit. Yet as our Lord himself asked, 'What is truth?' Sometimes, Brother Lukas, what appears to be truth from one perspective may be revealed as error from another."

He reached into his robe and withdrew a small leather-bound book. "I have brought something that might assist in your research—a copy of the Vatican Observatory's calculations of all major astronomical events visible from Europe between the years 500 and 1000 AD. A reference work of considerable precision."

I accepted the book, noting with interest that it bore no library markings, no indication of provenance. "You are most generous, Doctor Visconti."

"The Church supports proper scholarship," he replied. "And proper conclusions based on that scholarship."

Our audience concluded shortly thereafter, with assurances from the abbot that I would continue my work with all due diligence and report any findings of significance. As I turned to leave, Visconti called after me.

"One more thing, Brother Lukas. Should you encounter any texts bearing a certain symbol—a circle quartered by a cross—I would be most interested to examine them. Such works often contain... theological errors that require correction."

I bowed again, my face carefully neutral. "I will keep that in mind, Doctor Visconti."