Chapter Three: A Scolaris Gestos II

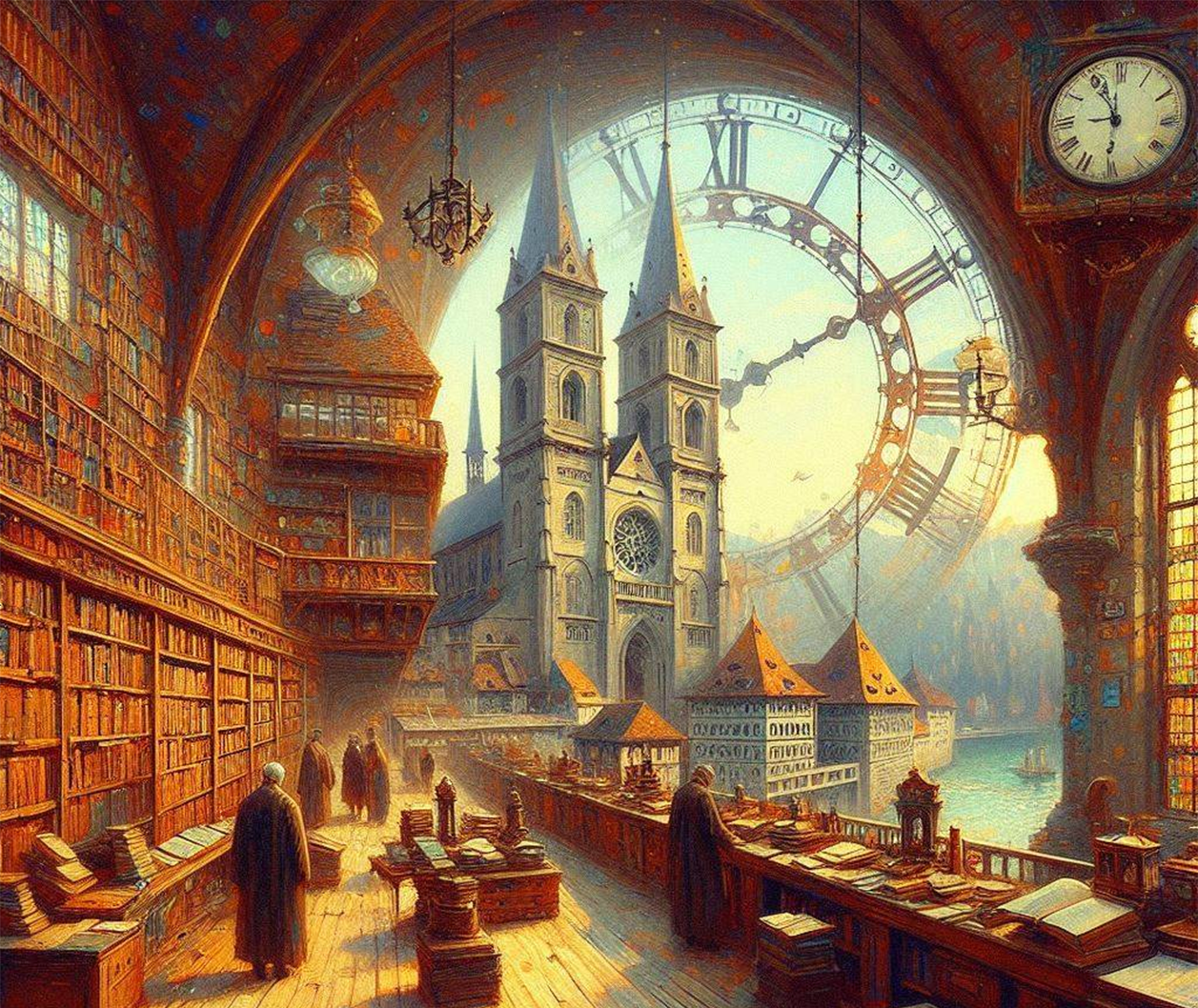

As soon as I was certain he was gone, I began my exploration in earnest, starting with a bundle of correspondence tied with faded red ribbon. The letters were addressed to Abbot Waldo of Reichenau, dated between 786 and 791—during the reign of Charlemagne, if the accepted chronology was to be believed. But what if those dates were fabrications? What clues might reveal the truth?

I examined the parchment itself first, noting its thickness, the quality of the preparation, the type of ink used. Nothing immediately struck me as anachronistic, but then, if this deception had been carried out with care, one would expect the material details to be consistent with the purported era.

Next, I scrutinized the script—a Carolingian minuscule, as would be expected for documents of this period. But here, I noticed something curious. The letter forms were almost too perfect, too consistent with what one would expect from a scribe of the late eighth century. There was none of the hesitation, the experimentation one might expect during a period when this script was still evolving.

It was as if the scribe knew exactly what Carolingian minuscule was supposed to look like, rather than participating in its natural development.

I made a note of this observation in a small journal I kept concealed within my habit, then turned to the content of the letters. They concerned mundane matters—the transport of religious texts, disputes over vineyard boundaries, arrangements for the visit of a papal legate. Yet even here, I found myself noticing peculiarities.

References to events and persons seemed oddly disconnected, as if the writer were constructing a narrative rather than living within it. There was a letter mentioning "the recent synod at Frankfurt," but with no elaboration on what had been discussed there—as if the sender knew the recipient would understand the reference not from shared experience, but from a common script.

More telling still were the absences. No mention of weather unusual enough to remark upon, no references to local events not already documented in the official histories, no personal details that might anchor these people in a lived reality.

By midday, I had filled several pages of my hidden journal with observations, each insignificant on its own, but together forming a pattern that made my skin prickle with excitement and unease. The documents read like performances of history rather than artifacts of it.

I attended the midday office as promised, standing among my brothers in the abbey church, reciting the familiar psalms with my lips while my mind continued to race with implications. If these documents from the supposed eighth century were forgeries, then who had created them? And why maintain such an elaborate fiction across all of Christendom?

The forbidden manuscript had named someone called "Gregorius, who forged time." But which Gregorius? Pope Gregory the Great had died in 604, before the phantom centuries supposedly began. Gregory II reigned from 715 to 731, well within the contested period. But Gregory VII, the great reformer, had ruled from 1073 to 1085, after the alleged insertion of false years.

As we chanted the Deus in Adiutorium, I found myself counting the popes named Gregory, trying to determine which might have had the motive and opportunity to perpetrate such a fraud.

"Brother Lukas."

I snapped back to awareness, realizing that the office had ended and the brothers were filing out of the church. Abbot Gerhardt stood before me, his heavy brows drawn together in concern.

"Forgive me, Father Abbot," I said, bowing my head. "I was lost in prayer."

"Indeed." His tone suggested he did not believe me. "Father Umbertus tells me you have been... distracted of late."

"I have been absorbed in my work on the Reichenau manuscripts," I said carefully. "They present certain challenges of interpretation."

"So I understand." He studied me, his eyes sharp beneath their bushy brows. "Remember, Brother Lukas, that our purpose here is not merely scholarship, but the greater glory of God. Do not let yourself become so entangled in the minutiae of texts that you lose sight of their ultimate purpose."

"Yes, Father Abbot."

He placed a hand on my shoulder, the gesture both paternal and warning. "Father Umbertus speaks highly of your intellect, but he also expresses concern about your... curiosity. It is good for a monk to ask questions, but better still to accept that some questions have no answers in this life."

I recognized the echo of Umbertus's warning in his words. How much had the old librarian told him? Did the abbot know about the forbidden manuscript? Was he, too, part of whatever conspiracy had hidden it away?

"I will reflect on your wisdom, Father Abbot," I said, keeping my voice humble.

"See that you do." He removed his hand and stepped back. "I would not wish to see your considerable talents directed elsewhere. The abbey of Saint Gallen has been your home for many years now. It would be a shame if that were to change."

Another threat, more explicit than Adelbert's but less so than Umbertus's. I was being warned from all sides, it seemed. Yet these warnings only served to convince me further that I was on the trail of something significant. If the phantom centuries were merely the fantasy of some deluded scribe, why such concerted efforts to dissuade me from investigating?