Chapter Four: Defectus Eclipsus V

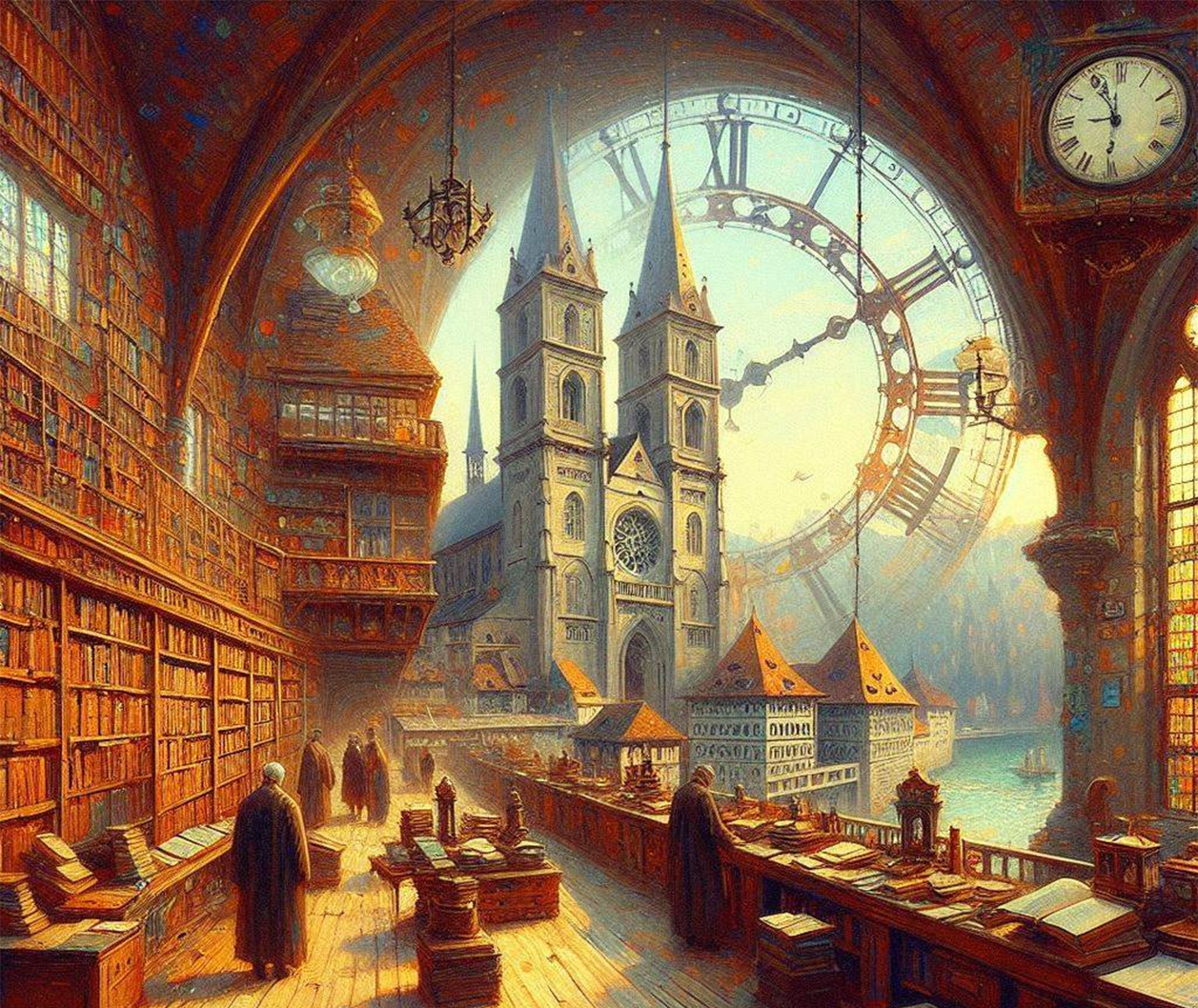

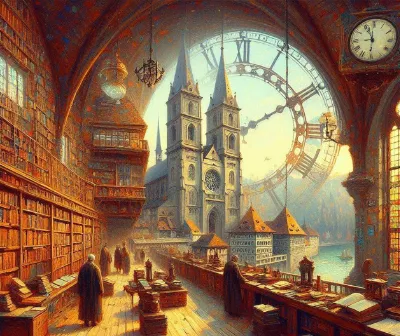

The library was abuzz with activity when we arrived. Several brothers clustered around a table where manuscripts were being carefully laid out, their parchment pages brittle with age. Father Umbertus stood over them, his expression a mixture of scholarly excitement and what looked suspiciously like fear.

And there, examining one of the manuscripts through a magnifying glass, was Doctor Visconti. He looked up as I entered, his dark eyes narrowing.

"Ah, Brother Lukas," he said smoothly. "How fortunate that you have joined us. Your expertise may be valuable in assessing these... unusual documents."

I approached the table cautiously. The manuscripts were indeed unlike any I had seen before. The parchment was darkened with age, but the script remained legible—a strange hybrid of Greek uncial and some form of runic writing that I could not identify.

"Where exactly were these found?" I asked, addressing the question to Father Umbertus rather than Visconti.

"Behind a sealed wall in the eastern wing," Umbertus replied. "The stonemasons discovered a cavity while repairing water damage. Inside was a small chamber containing these documents and this."

He held up a metal object—a disk about the size of a man's palm, made of what appeared to be bronze. On its face was a familiar symbol: a circle quartered by a cross.

My breath caught. The same symbol that had adorned the forbidden manuscript, now appearing on an artifact found hidden within the abbey's walls. This could not be coincidence.

"Remarkable," said Visconti, though his tone suggested he found it anything but surprising. "A token of the Ordo Temporis, unless I miss my guess."

"The Order of Time?" I translated, feigning ignorance. "I am not familiar with such an organization."

"Few are," Visconti replied. "It was a monastic order that flourished briefly during the Carolingian period, dedicated to the study of chronology and astronomy. They were eventually absorbed into the Benedictines, I believe."

His explanation sounded plausible, even scholarly, but I recognized it for what it was: a carefully constructed fiction designed to deflect inquiry from the truth.

I picked up one of the manuscripts, examining the script more closely. Though I could not read it, certain patterns emerged—numbers, astronomical symbols, what appeared to be dates of some kind.

"Has anyone been able to translate any of this?" I asked.

"Not yet," said Father Umbertus. "We've only just begun our examination. Doctor Visconti has kindly offered his expertise in ancient scripts."

"Indeed," said Visconti. "The Vatican possesses extensive resources for such work. I suggest these documents be transported to Rome for proper study."

My heart sank. If these manuscripts left the abbey, I might never learn their contents. And if they did indeed contain evidence of the phantom centuries, they would surely disappear into the Vatican's secret archives, never to be seen again.

"Surely we have the expertise to at least attempt a preliminary translation here," I suggested. "Brother Oswald is skilled in ancient languages, and Brother Clemens might help with any astronomical references."

Father Umbertus hesitated, clearly torn between scholarly pride in the abbey's capabilities and deference to Vatican authority.

"I propose a compromise," said Visconti smoothly. "I will remain at Saint Gallen for a few more days to assist with initial assessments. If the documents prove to be of exceptional importance, we can then discuss their temporary relocation to Rome."

Relief flooded through me. A few days might be enough to discover what secrets these manuscripts held—if I could find a way to examine them without Visconti's watchful presence.

As the discussion continued around me, I studied the manuscripts more carefully, trying to commit as much as possible to memory. One page contained what appeared to be a star chart, with positions marked in the strange hybrid script. Another showed what might be eclipse calculations, with diagrams similar to those I had seen in Brother Clemens's books.

Most intriguing of all was a document that seemed to list a sequence of names or titles, each accompanied by dates. Though I could not read the script, the pattern was unmistakable—it resembled a chronicle or regnal list. If this was a record of rulers or events from the phantom centuries, it might provide crucial evidence of the chronological deception.

"These will require careful study," I said, looking up to find Visconti's eyes fixed on me with unsettling intensity.

"Indeed they will, Brother Lukas," he replied. "Indeed they will."

The examination continued until vespers, with each manuscript being carefully cataloged and described. I remained, watching, listening, gathering what information I could without revealing my suspicions. When the bell rang for the evening office, Father Umbertus instructed that the documents be secured in the abbey's strongest chest, with both he and Doctor Visconti holding keys.

As we filed out of the library, Visconti fell into step beside me. "Fascinating discoveries today, wouldn't you agree, Brother Lukas?"

"Most fascinating," I replied neutrally.

"It is remarkable how the past continually reveals new secrets," he continued. "Though sometimes, those secrets are best left undisturbed."

I inclined my head slightly in acknowledgment but said nothing.

"I understand you spent some time in Brother Clemens's observatory today," Visconti added casually. "Did you find my astronomical reference helpful?"

"Very," I lied. "Though I confess some of the calculations are beyond my mathematical abilities."

"Yes, celestial mechanics can be quite complex. Even the great Tycho Brahe occasionally found himself confounded by apparent contradictions in his observations. It took Kepler's genius to resolve these discrepancies within the framework of elliptical orbits."

"The pursuit of astronomical truth has often been fraught with difficulty," I observed cautiously. "One thinks of Galileo's unfortunate conflict with Pope Urban VIII."

Visconti's smile tightened. "A regrettable episode, though perhaps an instructive one. Galileo might have continued his work unimpeded had he shown more discretion in how he presented his findings."

The warning could not have been clearer. Proceed with caution, or suffer consequences.