Chapter Two: Bibliothecarius Scriptor Timoris

"For whoso speaketh of Time's lie, seeketh his own destruction, wherein the keepers of chronology shall pursue him like water pursues the lowlands."

— Anonymous marginalia, Codex Sangallensis 193

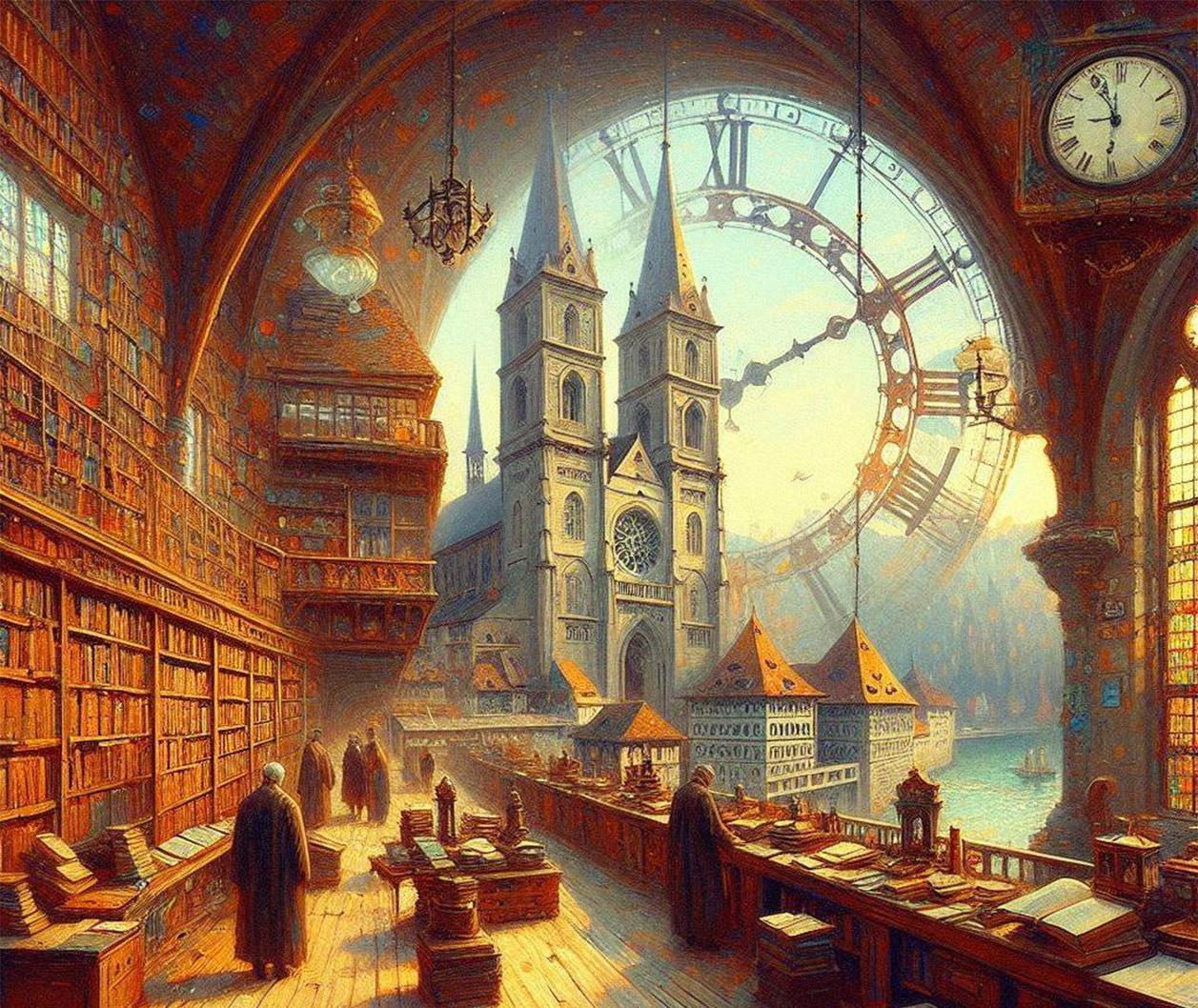

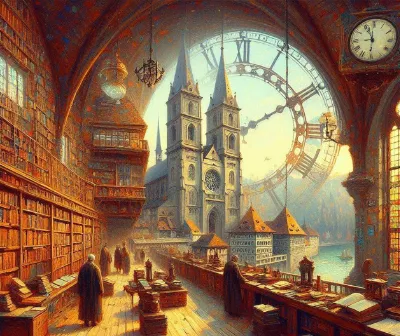

I could still feel the weight of the mysterious tome in my hands as I made my way to Father Umbertus's private study. The symbols on its cover—a circle quartered by a cross—seemed to burn in my mind's eye. What had I stumbled upon in that forgotten corner of our library? And why had the sight of it transformed our normally impassive librarian into a man seized by fear?

These questions churned within me as I approached his door. I had been summoned, as I knew I would be. Father Umbertus von Kreuzlingen had been the keeper of Saint Gallen's literary treasures for longer than I had been alive—thirty-seven years of vigilance that had etched deep lines into his face and turned his beard the color of aged vellum. He was not a man easily disturbed. Yet when he had seen the book in my hands, his face had drained of color as if he beheld not parchment and leather, but the very gates of Hell.

I knocked, my knuckles against the ancient oak sounding unnaturally loud in the hushed corridor.

"Enter," came his voice, taut as a bowstring.

I opened the door to find him seated behind his desk, hands folded atop its polished surface. His eyes followed me as I entered, but I noticed his gaze dart momentarily to a drawer on his right side. The book, I surmised, had been secured there.

"You wished to see me, Father Umbertus?" I kept my voice respectful, neutral, though my heart raced with anticipation.

"Yes." He gestured to the chair across from his desk. "Sit."

I obeyed, perching on the edge of the hard wooden seat, my back straight, my hands folded in my lap as befitted a dutiful monk. But my eyes, I fear, betrayed me—straying to the drawer where I suspected the mysterious manuscript lay hidden.

"Brother Lukas, do you know the sin of Curiositas?"

The question caught me off guard. I had expected a reprimand, perhaps even a penance, but not a theological inquiry.

"Saint Augustine spoke of it as the disease of curiosity," I answered carefully, "an appetite for knowledge beyond what is proper."

"Precisely." He nodded, his expression grave. "There is knowledge intended for men, and knowledge reserved for God alone. The manuscript you found today belongs to the latter category."

I could not help myself. "But Father, if what it says is true—"

"Truth?" He cut me off, his voice sharp as a blade. "What truth? The ravings of some anonymous scribe? The delusions of a man who would rewrite the very flow of time itself?"

"There were calculations," I pressed, leaning forward. "And astronomical observations. They could be checked—"

"They were fabricated! Mad delusions of a disordered mind!" His fist came down on the desk with such force that the candlestick jumped, sending shadows dancing across the stone walls.

I fell silent, though my mind raced. It was true. Even in modern times, there were the likes of Daniel Rohr, who questioned the accepted Egyptian chronology, which was itself known as the New Chronology on the basis of its correction of the previous one constructed by 19th century Egyptologists.

And yet, there was something unusual about Father Umbertus’s uncharacteristic passion. It was not as if he was merely dismissing the book as nonsense, more that he was warning me away from it with the desperation of a man who stands between an ignorant innocent and an abyss.

"Brother Lukas," he continued, his tone softening, "I have watched you grow from a novice into a most promising scholar. Your dedication to our library, to the preservation of knowledge, has been exemplary. But you must know there are paths of inquiry that lead not to enlightenment, but rather, to ruin."

His eyes, pale blue behind networks of fine wrinkles, fixed on me with an intensity that made me want to shrink back into my seat.

"Have you forgotten Man’s very first lesson about knowledge, and what the cost of its pursuit may be?"

I considered his words. "Are you suggesting that this manuscript contains... divinely forbidden knowledge?"

He hesitated, and in that pause, I read volumes. Father Umbertus, scholar and theologian, was not inclined to declare the book heretical or demonic—which meant its contents troubled him on a different, more material level.

"I am suggesting," he said at last, choosing his words with evident care, "that there are questions we are not equipped to answer, mysteries we cannot unravel without unraveling ourselves in the process."

He opened a different drawer and withdrew a small key, which he pushed across the desk toward me.

"This opens the cabinet in the southwestern corner of the restricted collection. Place these documents there—" he handed me a stack of unremarkable parchments, routine correspondence regarding the monastery's finances, "—and forget what you saw yesterday. That is both an instruction and my heartfelt advice."

I took the key, feeling its cold weight in my palm. "And the manuscript?"

"I will see to it personally."

Our eyes met across the desk—his pleading, mine burning with questions I dared not voice. For a moment, I saw something unexpected in those aged eyes: recognition. As if he looked not at me, but at a younger version of himself.

"Brother Lukas," he said, his voice barely above a whisper, "I speak not as your superior, but as one who cares deeply for your soul. Some doors, once opened, cannot be closed. Some knowledge, once gained, cannot be unlearned. For your own peace, I beg you: let this matter rest."

I rose, clutching the key and documents, sensing our interview was at an end. "As you wish, Father." I bowed and turned to leave, but at the door, I paused. One question burned hotter than all others, and I could not depart without asking it.

"One question, if I may?"

He tensed visibly. "Yes?"

"The symbol on the binding. What does it represent?"

He closed his eyes briefly, and I watched his internal struggle play across his features. When he answered, his voice was low, as if he feared being overheard.

"It is the sigil of those who claim to be the guardians of true time. Now go, and speak of this to no one."

I bowed again and left, my mind reeling. Guardians of true time? If time could have guardians, that implied it could be threatened, altered, perhaps even falsified—just as the manuscript asserted.