Episode 10: The State's Rebuttal

“Order!” The judge banged his gavel. “Profesora Castillo, I will hear you now.”

“Thank you, your honor.” Senator Castillo put a hand on her hip and gestured with her pad toward the defense table. “Let me begin with the rule of construction in matters of caption and substance for the statute. These questions have all been settled in our state, and support the validity of the GAIA Act. All that is necessary under our law is that the caption of the act and the body of the act shall be germane, the one to the other. The caption of the act shall simply state enough to put the legislature on notice when the caption is read as to what they – the legislature – are passing upon. If the defense has any laws from deep in the heart of Texas that conflict with it, or will throw any light on it, we will be glad to hear about it. I am told they have many great lawyers and courts there from whom we might learn.

“The United States Supreme Court has also sustained our contention in this matter.

“As to the scientific proposition, the words employed in the constitution or a statute are to be taken in their natural and popular sense, unless they are technical legal terms, in which event they are to be taken in their technical sense. But this is not such a statute. This is not a statute that requires the outside assistance of Texas to define. Any high school student can understand the plain meaning of the title and text of the statute.”

“I object, your honor,” Senator Travis rose. “We are discussing the constitutionality of this indictment on a motion to quash. And I would like to say here, though I do not mean to interrupt the… Profesora, that I do not consider further allusion to geographical parts of the country as particularly necessary, such as references to Texas. I am here, rightfully, as an American citizen.”

“I am confident everything Profesora Castillo says is in good humor,” the judge assured Senator Travis. “I want you to always remember that you are our guest, and that we accord you the same privileges and rights and courtesies that we do any other lawyer.”

“Your honor,” Travis replied, “I want to have it understood I deeply appreciate the hospitality of the court and the people of this state, and the courtesies that are being extended to me at this time, but I also want it understood that while we are in this courtroom I am here, not as a guest, but as a lawyer.”

“Your honor,” Castillo rebutted, “I have the highest regard for the distinguished lawyer representing the defense. I have no respect, however, for his opinion as to the law. I do not believe he accurately represents the law, and I have a right to say so before the court. It is not my intent to insult or hurt the feelings of defense counsel. I will merely be sharing the opinions of our state supreme court and the U.S. supreme court – opinions that contradict his claims.

“Now, if your honor please, as I understand the defense position, they say the caption doesn't correspond with the body of the act. I want to call the court's attention to this.

“A general title to an act is one which is full and comprehensive and covers all legislation germane to the general subject stated. A title may cover more than the body but it must not cover less. It need not index the details of the act, nor give a synopsis thereof.

“You have the citation in our brief, your honor,” Castillo explained.

“If anything,” she continued, “the caption of the statute is broader than the act itself. The caption states that the act prohibits the teaching of the biological theory of sex. The act provides more specificity in forbidding the instruction of any theory that gender identity has a biological meaning independent of any person's chosen preference.”

“You are insisting,” the judge asked, “that if the caption is broader than the body of the act that it doesn't invalidate the act?”

“Our insistence,” Castillo clarified, “is that the only objection that could be made is that the caption is in fact broader than the act and it is well settled in our state that that would not invalidate it. The caption broadly prohibits ‘the teaching of the biological theory of sex.’ The act more narrowly prohibits teaching ‘that gender identity has a biological meaning independent of any person's chosen preference.’ We have a rule of construction in our state which prohibits the court from placing an absurd construction on the act. Any construction that somehow construes the biological theory of sex as being narrower in scope than a specific theory teaching that gender identity has a biological meaning independent of any person's chosen preference certainly would be an absurd construction.”

Castillo flipped her legal pad to the next page. “The next objection raised by the defense is Section 13, Article II of the state constitution, which admonishes our legislature to cherish literature and science. The controlling case, on the proposition, is the case of Leeper versus the State, where the uniform textbook law was attacked, and numerous questions raised. In a very lengthy opinion by the supreme court, they placed within the legislature the absolute power to control the public school system.”

Castillo retrieved a printout from the prosecution table. “In this case, if your honor please, I want to read from it.

“We are of the opinion that the legislature under the constitutional provisions, may as well establish a uniform system of schools and taxation and a uniform system of criminal law and, of course, to execute them.”

Castillo set down the printout and retrieved her pad.

“This dictum is to cherish literature and science. What else could it mean? And who, who in the last analysis, if the court pleases, has the right to say whether they have or not? It is merely directory to the legislature.”

Castillo pulled out another printout. “We also have the Meyer case in which the Supreme Court of the United States affirmed ‘the state’s power to prescribe a curriculum for institutions which it supports.’ Our state has a right to prescribe the curriculum in those schools supported and maintained by the money that is paid into the public treasury from the pockets of the taxpayers of this county and state.”

She retrieved her pad. “This brings us to the defense’s third objection, that the GAIA Act violates the freedom of speech protected by both the state constitution and, through the fourteenth amendment, by the U.S. constitution as well.

“Suppose our state employs a teacher of mathematics. Under the defense argument, that teacher could exercise his freedom of speech to teach literature, or architecture, or history, or whatever he might please without the state having any recourse. If that teacher wants to expound upon literature, he may do so in some other place. When you take the sovereign’s coin, you must do the sovereign’s bidding. If you have been hired by the state to teach mathematics, you must do as the state bids, or exercise your freedom of speech elsewhere.

“The defense’s fourth and fifth arguments claim that the act and indictment are void for vagueness. Dr. Andrews is before this court because he taught that gender identity has a biological meaning independent of any person's chosen preference. What is there vague and indefinite and uncertain about that?”

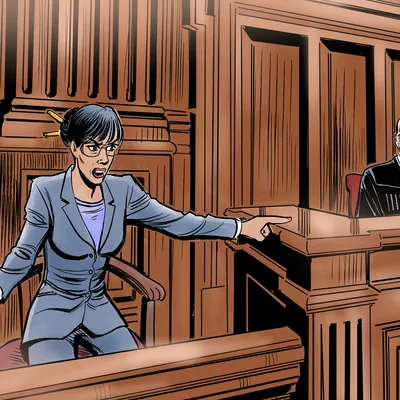

Castillo turned to face Travis. “You didn’t prepare a brief here to defend him on a charge of arson, did you?” she asked rhetorically.

“Dr. Andrews is not here for shoplifting… or jaywalking… or forgery, and he knows it. And counsel for the defense knows it. Dr. Andrews is here for teaching a theory that denies the gender definition adopted by one of his students. And that, if your honor please, is sufficient. The act is sufficient to notify him what he is charged with, and therefore the indictment is sufficient, and it complies with the requirements of the law.

“Finally, the defense argues that the act and the indictment violates Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States. Here again, we return to the Meyer case: the state has the power to prescribe a curriculum for institutions which it supports.

“Might I ask a question?” Travis rose to his feet.

“I do not object, your honor,” Castillo confirmed.

“Go ahead, Professor,” the judge consented.

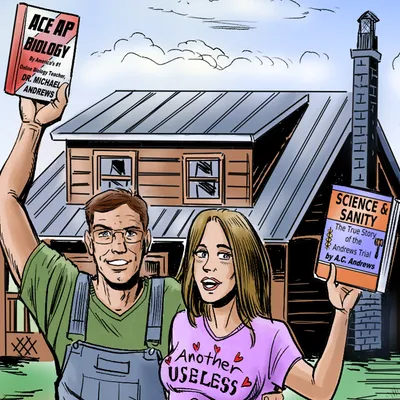

“Did the state, under the power you have referred to, prescribe the book which Dr. Andrews taught in the schools?”

Castillo was taken aback. “Did they do what?”

“Did the state,” Travis repeated more slowly and with greater emphasis, “under the power you have referred to, prescribe the book from which Dr. Andrews taught?

“There is,” Castillo paused, “no act on that as I understand it.”

“I thought you just stated,” Travis tried to pin her down, “that the state prescribed the curriculum, and I assume, school books; did they prescribe the school book that Dr. Andrews was using?”

“I said they had a right to,” Castillo clarified.

“Did the state exercise that right?” Travis asked. “How did Dr. Andrews get the book? Was it given to him by the state?”

“That is not relevant at this time. Why?” Castillo put a hand on her hip. “Do you want to put ME on the witness stand?”

“We will take a few minutes recess,” the judge banged his gavel, interrupting the line of questioning.

“Nice line of questions,” Andrews quietly complimented Travis. “You had her cornered. You’ll go after her again after the recess?”

“Saved by the bell,” Travis acknowledged, “or more specifically, by the judge. No, I made the point. No need to press it further. For now. We’ll get back to it. Eventually.”

Andrews frowned. After having been made a punching bag for so long, he was eager to see more blows landed on the other side.