Episode 14: Ruling on the Motion to Quash

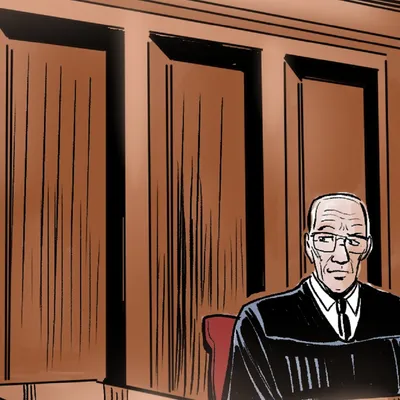

“All rise,” the bailiff proclaimed as the judge re-entered the courtroom, that afternoon. The courtroom was once again packed to overflowing with observers and the press.

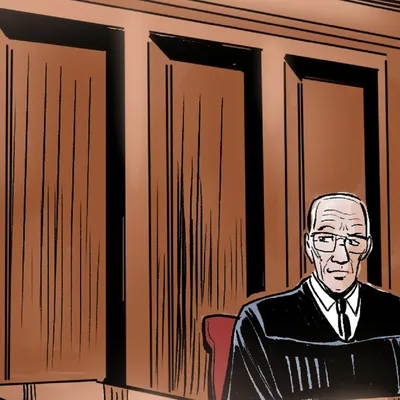

The judge took his seat at the bench. “Be seated.”

“Now, I am about to read a summary of my opinion on the motion to quash the indictment. I expect absolute order in the courtroom because people are entitled to hear this opinion.”

That announcement triggered a wave of murmuring and rustling as the journalists present prepared to report the outcome.

“Let us have order,” the judge again insisted.

The courtroom finally quieted.

“This case is now before me on a motion to quash the indictment,” he began.

“First, the defense argues that the caption and substance of the act violates Section 17, Article II of the State Constitution, origin and frame of bills.

“In my judgment, the caption of this act is sufficient to put any member of the legislature on notice as to what the nature of the proposed legislation is, and that really the caption is more comprehensive than the body of the act. Therefore, I am content to overrule this ground.

“Second, the defense argues that the act violates Section 13 Article II of the State Constitution, the legislature’s duty to cherish science.

“This section of the Constitution makes it the express duty of every general assembly, at all times, to foster, and cherish literature and science. As one of the chief means of accomplishing this most important purpose, the Constitution contemplated the establishment of a common school system, and provided the common school fund. But this provision of the Constitution is merely directory to the legislature and indicates the popular feeling and the public policy of the people of the state on this great question. The courts are not concerned in questions of public policy or the motive that prompts the passage or enactment of any particular legislation. The policy, motive, or wisdom of the statutes address themselves to the legislative department of the state, and not the judicial department. Therefore, this court has no concern and no jurisdiction to pass upon this question, and is contented to overrule on this ground.

“Third, the defense argues that the act which is the basis of the indictment, and under which the defendant is charged with violating, is unconstitutional and void in that it violates Section 19, Article I of the State Constitution, freedom of speech and of the press.

“I cannot conceive how the teachers' rights under this provision of the Constitution would be violated by the act in issue. There is no law in this state that undertakes to compel this defendant, or any other citizen, to accept employment in the public schools. The relations between the teacher and his employer are purely contractual, and if his conscience constrains him to teach the biological theory of sex, he can find opportunities elsewhere in other schools in the state, to follow the dictates of his conscience, and give full expression to his beliefs and convictions upon this and other subjects without any interference from the state or its authorities, so far as this act is concerned. The court is pleased to overrule these grounds.

“The defense’s fourth and fifth arguments pertain to the indefiniteness, lack of certainty, and vagueness of the act and the indictment.

“The requirement, as the court, understands, is this: The description of the offense charged in the indictment must be sufficient in definiteness, certainty and precision to enable the accused to know what offense he is charged with and to understand the special nature of the charge he is called upon to answer; to enable the court to see from the indictment a definite offense, so that the court may apply its judgment and determine the penalty or punishment prescribed by way, and also to enable the accused to protect himself from a second prosecution for the same offense.

“A description distinguishing the offense from all other similar offenses is not required. That degree of precision in the descriptions of the particular offense cannot be given in the indictment so as to distinguish it per se from all other cases of a similar nature. Such discrimination amounting to identification must rest in averment by plea and in the proof, and its absence in description in indictment can be no test of the certainty required either for defense against the present prosecution or for protection against a future prosecution for the same matter.

“The description of a statutory offense in the words of the statute is sufficient; and renders the indictment sufficiently certain if it gives the defendant notice of the nature of the charge against him.

“The court is content that the act and indictment satisfy these criteria and is pleased to overrule on these grounds.

“Finally, defense argues that the act and the indictment violates Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States.

“To the extent the defense appeals to the protections under the United States Constitution for free speech, and for due process of the law with respect to indefiniteness or lack of certainty in the act or indictment, this court has already addressed those concerns.

“We find in the law and authorities submitted to us by the defense neither reason nor authority that suggests a doubt as to the power of the legislature to require a designated series of books to be used in school. Nor do we find reason to doubt the constitutionality of the legislature’s exercise of that power.

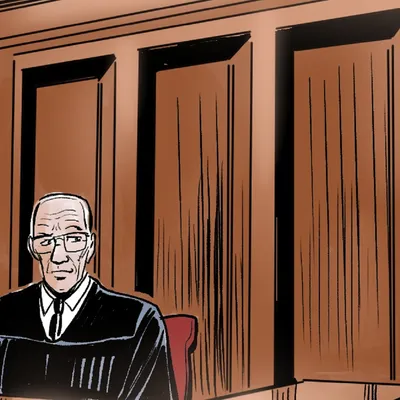

“The court, having passed on each ground chronologically, and given the reasons therefor, is now pleased to overrule the whole motion, and require the defendant to plead further.”

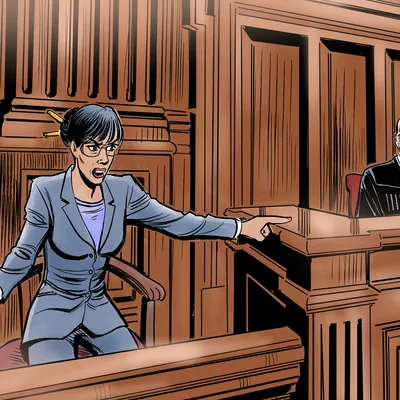

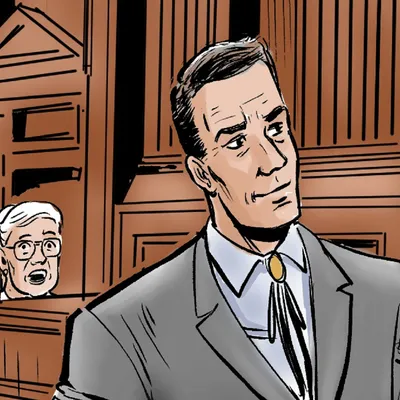

Senator Travis rose. “Your honor, we desire to enter an exception to your honor’s ruling in overruling our motion to quash the indictment and an exception to your honor’s holding the act under which Dr. Andrews is being prosecuted meets the requirements and is not in conflict with the Constitution of this state, or of the Constitution of the United States. We do this out of abundance of caution and to keep the record straight in event of an appeal.”

“So noted, Professor Travis,” the judge acknowledged.

“Are you ready to proceed now, Mr. District Attorney?”

The district attorney glanced over at Senator Castillo, who nodded her agreement. “I think so, your honor. We need a moment to call and assemble our witnesses.”

“Do so,” the judge instructed.

The district attorney stepped into the courtroom and ran through his witness list, confirming they were present in the courtroom.

“Professor Travis,” the judge asked, “do you require any time for a conference?”

“No, your honor,” he confirmed. “The defense is ready to proceed.”

The district attorney returned to his table.

“Are you ready to read the indictment?” the judge asked.

“The indictment has already been read, your honor,” the district attorney reminded the judge, but we can read it again.”

“Do so,” Judge Connor nodded his assent.