Episode 49: A Premature Conclusion

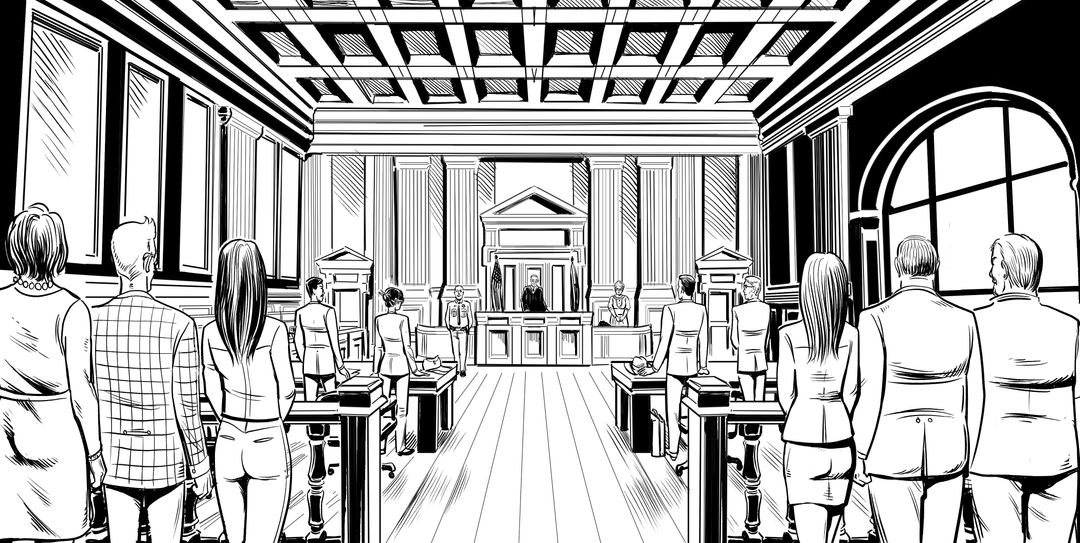

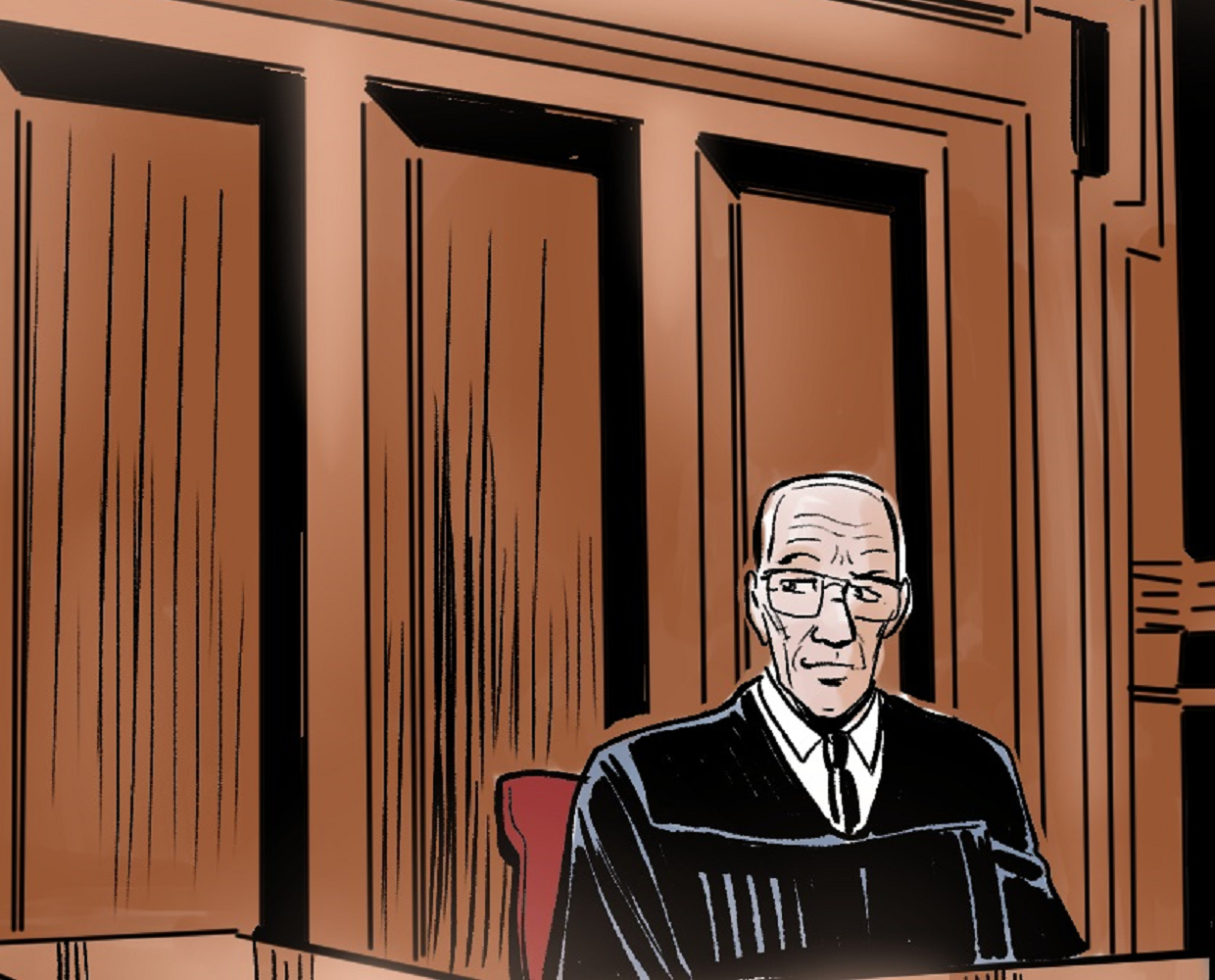

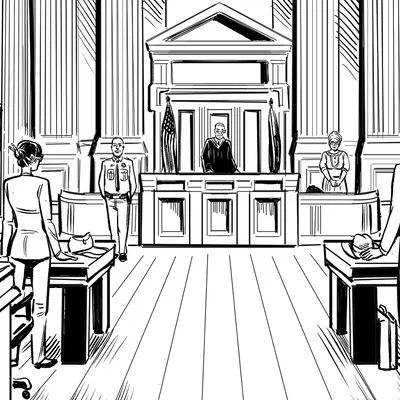

“Hear ye! Hear ye! All rise,” Deputy Martínez intoned as all stood within the courtroom. “The Fifth District Court in and for our great Commonwealth, the Honorable Jordan Connor presiding. God save this state and this honorable court. The case of the State versus Michael Philip Andrews. All those with business before this court draw near; you will be heard.”

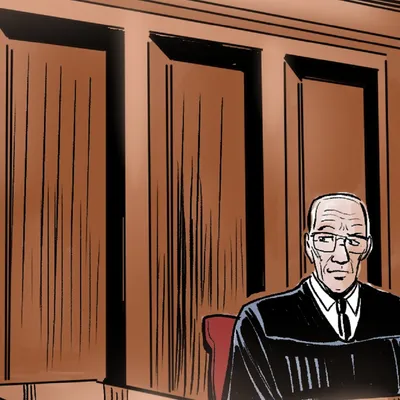

The judge walked into the courtroom and took his seat at the bench.

“Is the defense ready to offer a closing statement?” Judge Connor asked.

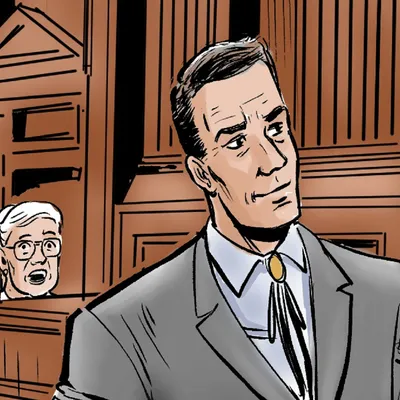

“Your honor,” Senator Travis rose, “Today is Friday. It’s been a long week, and I think to save time we will ask that the court instruct the jury to find the defendant guilty. We make no objection to that, and we think that should be done.”

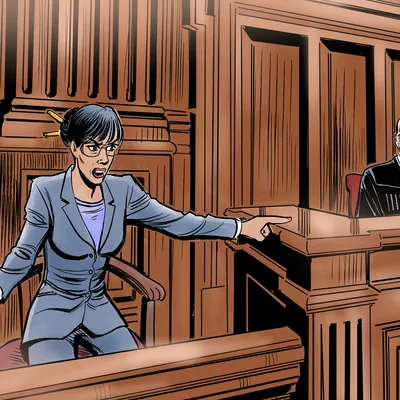

“Your honor,” Senator Castillo rose, “the state calls Professor Travis to the witness stand.”

Senator Travis turned to look at Senator Castillo. “I respectfully decline. I think we’ve had more than enough cross-examination.”

“Your honor,” Senator Castillo declared, “I agreed to be cross-examined on condition that I would get to call… Professor Travis to the stand.”

“If it pleases the court,” Senator Travis replied, “I am informed that stipulations must be in writing to be enforceable under your state’s procedure. The state has no business interpreting the silence of the defense as consent.”

“Objection!” Senator Castillo protested.

“On what grounds?” Judge Connor asked.

Senator Castillo paused. “That’s not fair!”

“Overruled,” Judge Connor declared. “Professor Travis,” he continued, “is your client changing his plea?”

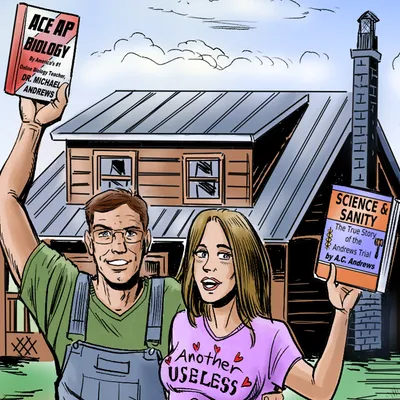

“No, your honor,” Senator Travis confirmed. “We maintain that the defendant is not guilty, but as the court has excluded our preferred testimony on the definition of gender affirmation and on the harmful consequences thereof, we cannot contradict or rebut the state’s testimony. There is no other logical outcome except that the jury find a verdict that we may carry to the higher court, purely as a matter of proper procedure. We do not think it is fair to the court or counsel on the other side or any of the many witnesses, journalists, and audience members here to waste a lot more of their time when we know this is not only the inevitable result, but also the best result for the case.”

“Your honor,” Senator Castillo interjected, “the state has no objection to a directed verdict of guilty, provided we be allowed to make our closing statement and place it on the record.”

“Your honor,” Senator Travis countered, “the defense is content to waive rights to closing statements and proceed to a directed verdict of guilt. Let us both stop wasting the time of this court, proceed to a directed verdict of guilt, and be done.”

“That does appear to be the best, the most efficient outcome,” the judge acknowledged, “and since the defense is waiving their closing statement, we shall skip the state’s closing statement as well.”

“Objection!” Senator Castillo insisted. “The state has invested considerable time and energy in preparing a closing statement, and we respectfully request leave of the court to present it and have it on the record.”

“Overruled,” Judge Connor stated. “I cannot very well allow you to present a closing statement unless the defense does as well.”

“I take exception!” Senator Castillo demanded. “My statement is important and deserves to be on the record and heard in court.”

“Noted,” Judge Connor pointed out, “but there is no provision to allow the state to introduce a summation, if the defense has waived its right to a summation. If you wish to present your summation, Profesora, you will have to wait until after the court stands adjourned.”

Senator Castillo slowly sank back into her seat, and Senator Travis took his as well. Judge Connor turned to face the jury box.

“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury,” he began his charge. “This is the case of the State versus Michael Philip Andrews where it is charged that the accused violated what is commonly known as the GAIA Act, that it shall be unlawful for any teacher in any of the Universities, and all other public schools of the State which are supported in whole or in part by the public school funds of the State, to teach any theory that denies the gender definition adopted by any person, and to teach instead that gender identity has a biological meaning independent of any person’s chosen preference.

“To this charge, the defendant has pleaded not guilty and thus is made up the issue for your determination. Before there can be a conviction, the state must make out its case beyond a reasonable doubt as to every essential and necessary element of the case.

“By the phrase ‘beyond a reasonable doubt,’ I do not mean any possible doubt that might arise, or such a doubt as an ingenuous mind might conjure up, but by reasonable doubt in legal parlance is meant such a doubt as would prevent your mind resting easy as to the guilt of the defendant.”

Senator Travis rose, “Your honor, may I say a few words to the jury about the directed verdict the defense has requested?”

“Very well,” the judge agreed.

“Ladies and gentlemen of the jury,” Senator Travis began, “we are sorry we did not have the opportunity we desired to present all the evidence we wished to lay before you, and that much of the evidence we did present, you have been instructed to ignore.

“The court has held under the law that much of the evidence we had is not admissible, so all we can do is to take an exception and carry it to a higher court to see whether the evidence is admissible or not. As far as this case stands before the jury, the court has told you very plainly that if you think my client taught the biology of sex determination, and you think that conflicts with gender definition, then you should find him guilty, and you heard the testimony of his students on that question. This case and this law will never be decided until or unless it gets to a higher court, and it cannot get to a higher court unless you bring in a verdict of guilty.

"So, I do not want any of you to think we are going to find any fault with you as to a verdict of guilt. I am frank to say, while we think it is wrong, and we ought to have been permitted to put in all our evidence, the court felt otherwise, as his honor had a right to hold.

“We cannot argue to you under the instructions given by the court. We cannot even explain to you why we think you should return a verdict of not guilty. We do not see how you could.

“We do not ask it.

“We think we will save our point and take it to the higher court and settle whether the law is good, and also whether his honor should have permitted the evidence.

“I guess that’s plain enough.”

Senator Travis took his seat.

“Mr. District Attorney?” the judge asked. “Any comment?”

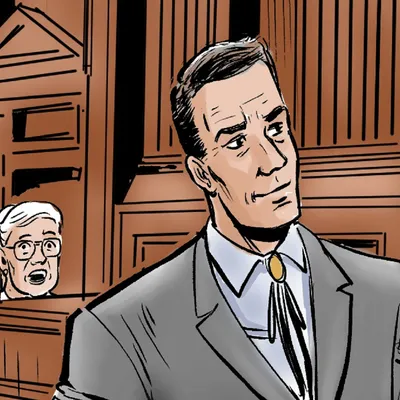

“I don’t think,” the district attorney rose, “that there is anything that can be said to the jury other than what Senator Travis said. Of course, this case will be thrashed out by the appellate courts. That is what both the defense and the state want. What Senator Travis wanted to say to you was that he wanted you to find his client guilty, but did not want to be in the position of pleading guilty, because it would destroy his rights in the appellate court.”

Judge Connor nodded. “Bailiff? Please escort the jury to the conference room for deliberation.”

The jury returned ten minutes later.

“Mr. Foreman,” the judge asked once court was back in session. Have you agreed on a verdict?”

“Yes, your honor,” the foreman declared. “We find the defendant, Michael Philip Andrews, guilty of violating the GAIA Act.”

“Did you fix the fine?” Judge Connor asked.

“No, your honor,” the foreman replied.

“Then, the court assesses the fine of $1,000, and suspends the sentence pending the inevitable appeal.”

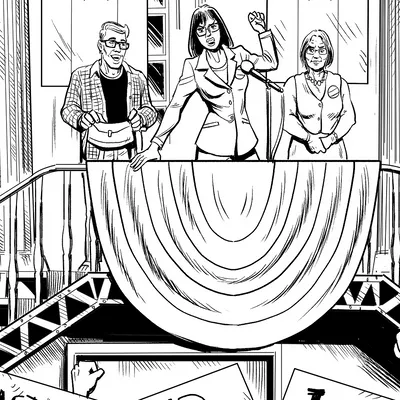

“The case of the State versus Michael Philip Andrews is now concluded,” the judge declared. “This court stands adjourned. Profesora, you may come forward to make your statement once I have departed.”