Episode 55

The Death of Mercury Wells

It was near to a full week before the Rangers arrived in Mercury Wells. The company of Rangers numbered six men. It was a sign of the pressure placed upon the governor in Austin that so many of the state’s lawmen were assigned to site of the massacre.

They found the town much as it was the day following the night of the raid. The only structures that remained standing were the town’s three-story hotel and the jailhouse. The rest—stores, saloons, homes and train station—were only described by the blackened skeletal remains of their frames. All that was left of the many tents were broad areas of scorched ground.

Bodies still swung from ropes looped over the arms of telegraph poles. Vultures sat atop the cross braces until dispersed by rifle shots. The lynching victims were lowered to the ground with as much respect as could be had given that each man was either naked or in shit-stained britches.

The hanged men were identified by Hector Nostrand, boss man off a local ranch. He mostly claimed to recognize them by body shape since the buzzards had consumed the softer flesh of their faces. The town mayor, town banker and a railroad man who often had business in Mercury Wells were his best guess as the identities of the hanged. None of that three made any kind of appearance in the week that followed the destruction of Mercury Wells. There were a dozen or more men strung up along the telegraph lines leading to the west. These were assumed to be storeowners or other types of businessmen once prominent in the town.

The death toll was near fifty in town not counting Chinese and whores. All of the town’s acting law enforcement, six county constables in total, and an assortment of cowboys, pimps, private police employed by the saloons and others had been executed by the still-unknown raiders. More than a hundred had been spared including the manager of the Grand Prairie, the organist at the Majestic and a prisoner, a blind man, held in the town jail.

The station house had been set ablaze and along with it a half mile section of track. The ties were soaked in lamp oil and touched off. The heat consumed the ties and caused the rails to twist like licorice sticks. A long train of waiting cattle cars were destroyed as well in the fire.

Aside from wholesale murder, arson and vandalism, the raiders also made off with three thousand head of longhorns awaiting transport in the stockyards. No account of how many horses were driven away. The vault that once rested inside the bank had been hauled off as well. Every corpse had been stripped of all valuables even to the amputation of fingers and ears to facilitate the removal of jewelry.

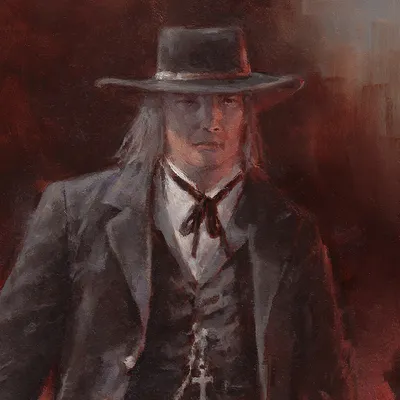

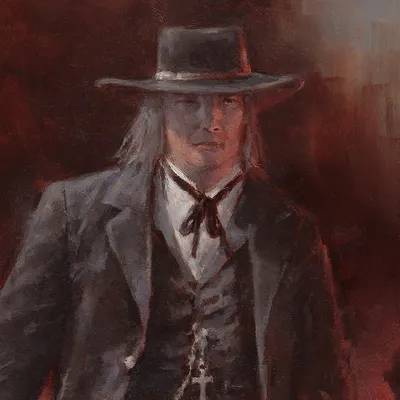

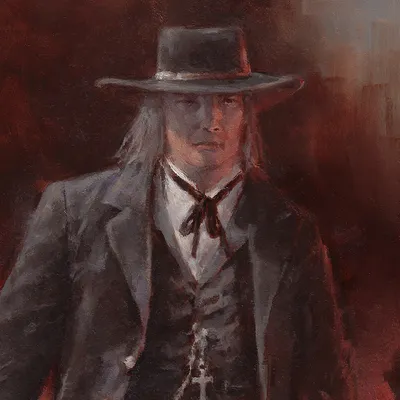

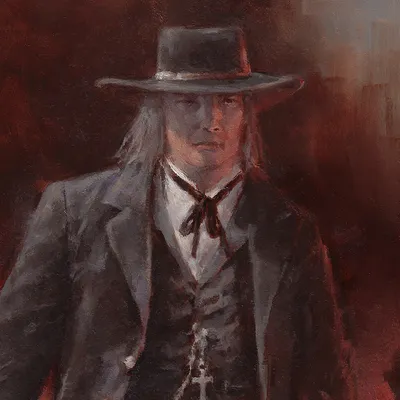

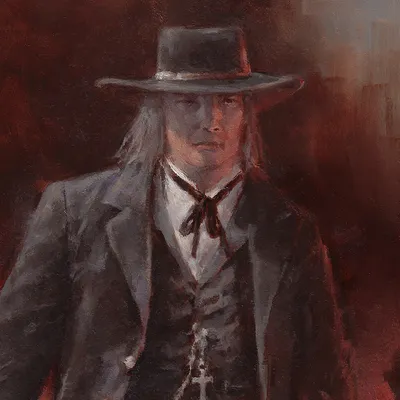

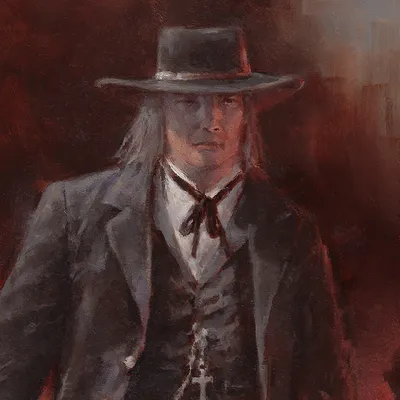

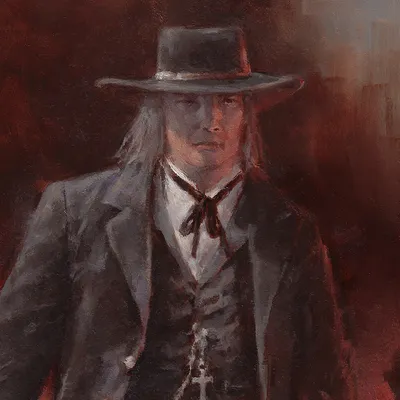

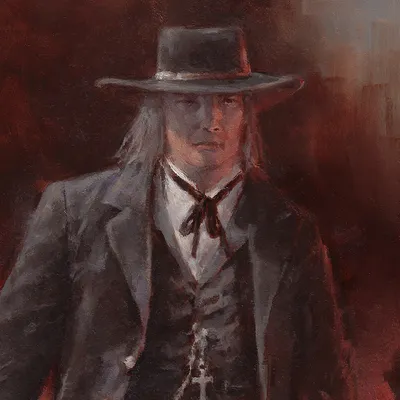

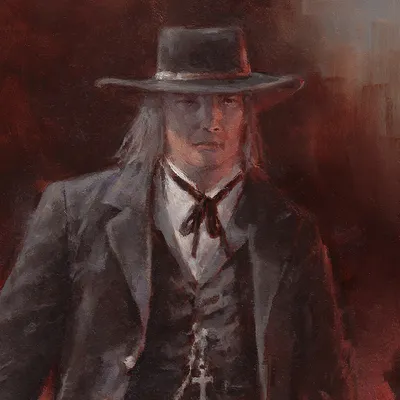

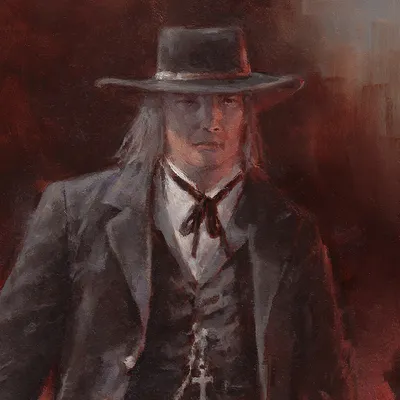

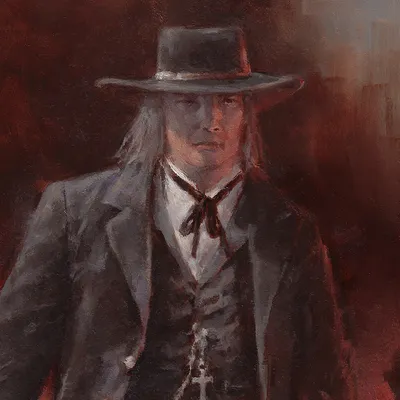

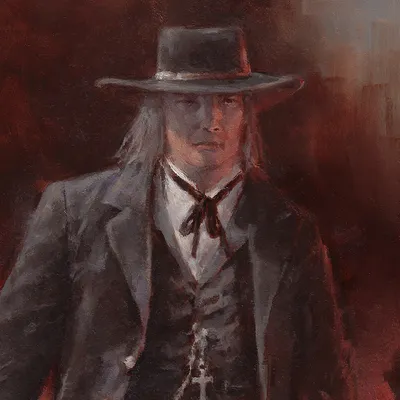

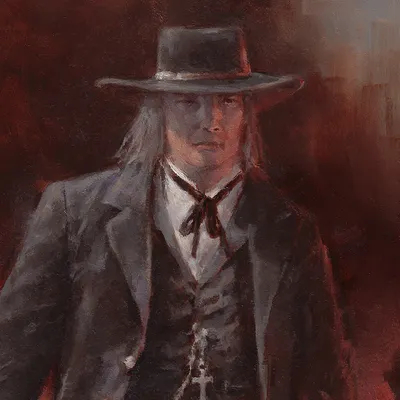

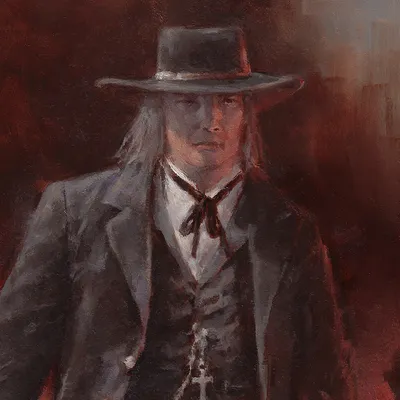

The most reliable witness to these horrors was a young half-breed boy who claimed to have seen “the whole thing” from a hiding place on the other side of the tracks. According to his claim, the raiders numbered in the thousands and were dressed as savages in war paint and feathers. The leader was a Mescalero or Comanche seven feet tall with a wolf’s head worn on his head and riding a horse black as a starless night.

The Rangers gave little credence to the boy’s story and even less to the testimony of the hotel manager and organist who swore to have seen nothing on the night of raid. There were no other witnesses worth a damn since most of the survivors had departed along the rail line to Barrow and destinations unknown.

The only worthwhile evidence that remained was the broad trail left by three thousand head of cattle still plain as ink on paper even after a week’s time. The Rangers followed the trail south until the sign split into two then four then six parties and more going off in as many different directions over the broken ground north of Big Bend country. To separate and chase after such small bands into the arroyos, washes, canyons and passes of the Chisos was folly even for as hardass a bunch as the Texas Rangers. Those beeves were in Mexico by now, far from the reach of any Lone Star authority. And the nameless men along with them.

All that was left was work for the railroad navvies. They would come to bury the dead and patch over the break in the rails. Along with its citizens, Mercury Wells had died as well. The ranches that could recover from their losses would have to drive the herds another hundred miles north. All that would remain of a once thriving town would be a water stop once the tank was rebuilt.