Episode 11

Devil's Freight

Ryderdale was one of the last to go and grabbed at Joe’s arm with desperate strength.

“I done terrible deeds, boy. Terrible things I can’t stop seeing,” Ryderdale said. A man not much older than twenty years, his face was the face of an old man, wasted by illness, gray and drawn.

Joe tried to pull away, but the man clung to him, drawing him closer to the bed, his voice a dry croaking whisper.

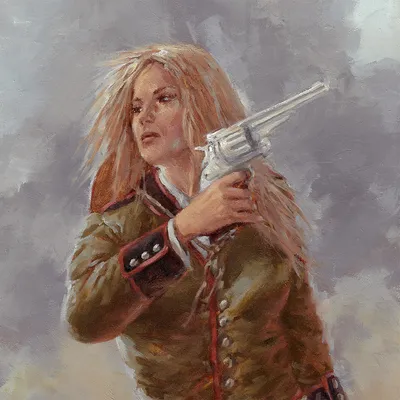

“There was a girl, a real pretty girl, back in Rio Blanco. Her folks and mine went to the same meetings, the preacher’s tent down by the river. She was awful pretty. Hair like…” The Texican was lost for the words to describe her further.

Joe tried to pry the man’s hand from his arm but could not.

“She made sport of me. Called me a dumb turd and thought it was funny. She was so pretty, and I wanted her to like me real bad. I caught her on the river path once, all alone. I taught her not to make sport of me. Taught her I was damn sure good enough for the likes of her.”

Joe surrendered to Ryderdale’s grip, listening in silence to the man’s confession.

“Couldn’t have her telling no one so I bashed in her brain with rock. Dragged her into the rushes and left her there. Waded the Blanco and never came back. Never saw no one I ever knowed ever again. I done things. Terrible things. But that was most terrible of all.”

His voice trailed away, mouth slack.

Joe sat on the edge of the bed until the hand gripping his arm relaxed and fell away. Joe hauled him from the bed and dragged the Texican out to drop him onto the growing pile of sinners who’d ridden the trail ahead of him to Perdition.

“Lo, we will go up unto the place which the Lord hath promised for we have sinned,” he said to himself, walking from the stinking pile and back to the cabins where the remaining men groaned aloud for the only deliverance he could grant them.

The clearing was getting grazed out. It was never meant to provide feed for so many mounts. Their own ponies, along with the mules and the horses they’d stolen, were chewing the grass down to bare dirt. Joe penned up Ben’s pinto mare along with a couple of other ponies. He mounted his roan and fired three rounds from the Walker into the air. The blasts had the horses up and milling. Waving a blanket in his hand, he herded the horses out through the trees and into the pass. Most of the mules trotted after. He rode drag, whooping and swinging the blanket over his head until the bulk of the herd was out through the pass and back into open country where they’d be free to find feed and water on their own.

He reined in the roan atop a shelf of rock and watched the mounts and drays canter away over a rise and out of sight in a smoke of yellow dust. Joe closed his eyes and raised his head to take in what felt like the first clean breath of air he’d had in a month. It smelled of cedar and sage. The sun warmed his face. For a fleeting second, he felt a rush, an urge to spur the roan down to follow the now renegade herd to the north and leave the pesthole of death and despair and low men far behind him.

Then he remembered that Ben Temple was still alive. Joe wheeled the roan around and headed back into the shadows of the pass at a walk. He meant to enjoy the ride as long as it lasted.

The following day saw the last of the raiders pass away. Joe left them where they lay in their sick beds and stepped from the cabin to see Ben Temple walking away in the sunshine in an unsteady gait, his Enfield rifle in his hands. Joe rushed to him and steadied him, helping Ben to a seat on a fallen log set by the cook fire for that purpose. He spoke low to Ben as he guided him to the fire.

“Get me a drink of water, son,” Ben said in reply and Joe rushed to the spring with a bucket.

Ben drank long and greedy from the bucket and handed it back and made a sweeping gesture.

Joe fetched a second bucket. Ben took it and upended it over his head. The ice-cold water splashed over his naked body, sluicing away weeks of accumulated filth.

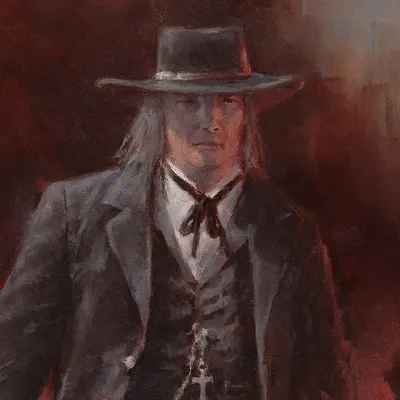

“Who’s left?” Ben said, blowing water out of his mustache and beard as he spoke. He was gaunt now from the ravages of the illness and loss of weight. But his voice was regaining its commanding timbre.

“You and me, Ben. That’s all. I just let most of the horses go free,” Joe said, and Ben nodded.

“It was the blankets or maybe the liquor,” Ben said. A shaking hand found Joe’s shoulder; the fingers squeezed.

“What are you saying?”

“I’ve heard of it before. Blankets full of pox. Whiskey tainted with poison. Those wagons might as well as had the Grim Reaper sitting on the drivers’ boxes.”

“You said they were part of a treaty, Ben.”

“I said I thought as much. And they may well have been. Only no treaty the government ever meant to keep. This devil’s freight was meant for the Kiowas, sure. Meant to kill them every buck, squaw and child,” he said and dropped his hand from Joe’s shoulder.

“Damnation,” Joe breathed.

“Didn’t drink as much of that brew as the others. Never been a souse. Glad of it now, I guess,” Ben said, head lowered, hand to his face.

“You guess? Well, you’re alive, ain’t you?” Joe said, laughing.

“That I am that, Snakehand,” Ben said and turned his face to Joe, a grim smile showing through his beard, eyes glassy.

“And blind as a bat on a moonless midnight.”