Episode 58

The Gurkha's Shovel

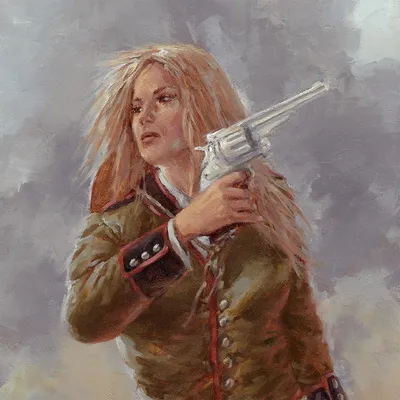

But young Emmett, a few years Arabella’s senior, died of a fever that also took his mother. Despondent over the loss, the earl took his own life and thus Archibald Paget-Thorpe assumed the earldom and his daughter became a lady.

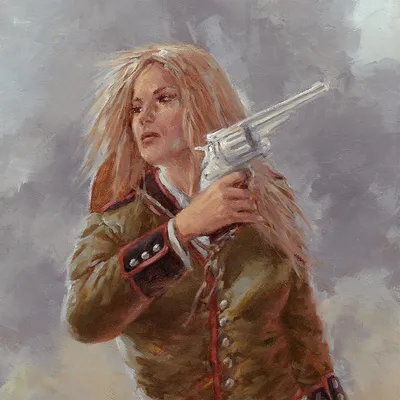

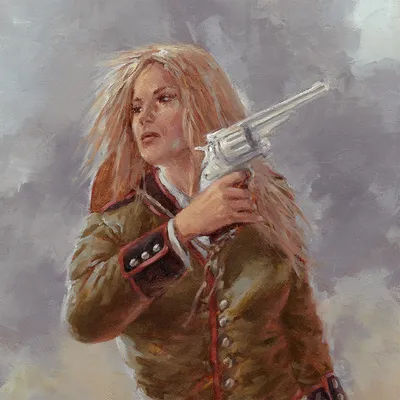

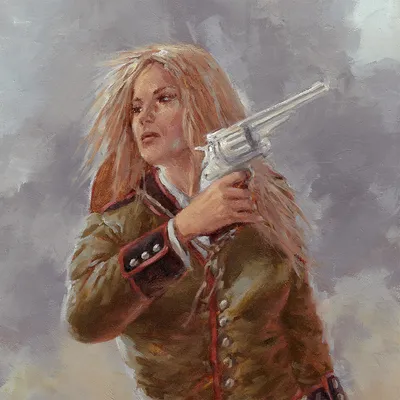

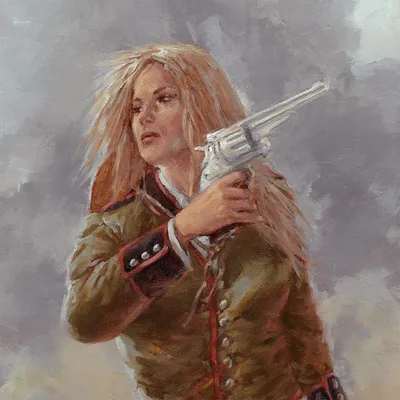

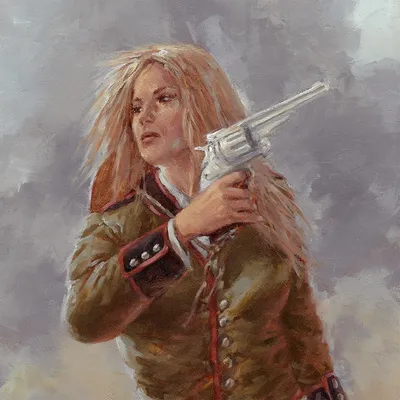

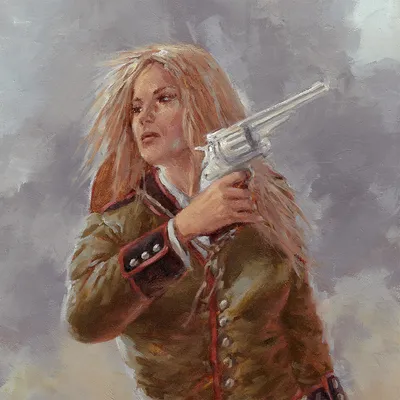

And, while it all seemed like something from a dream at first, father and daughter fell into their routines. The new earl pursued the science of xenobiology that had interested him in the Punjab and Arabella took to riding, hunting and improving her French as well as her fencing skills with the aid of tutors hired by her father.

It all became quite boring quite rapidly and Arabella grew to miss the exhilaration of the wild lands of her childhood that she left behind. Here, in the quiet shires and village greens, there was little promise of adventure.

Until the past few nights and the possibility of murderous poachers on the land.

A new sound rose out of the gloom below. A curious chirruping sound that came from the throat of no bird. Arabella strained her hearing to reach down the hill. It was part hoot and part bark. The sound of a ferret on the hunt.

But did it hunt alone?

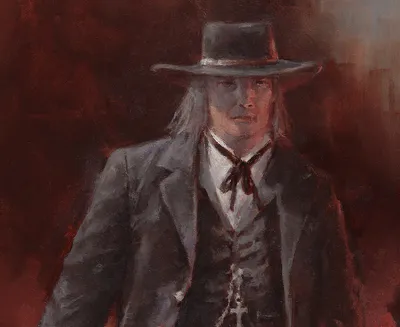

She looked over to where Rahul crouched nearly invisible, a darker shape against the shadows of the trees. She sensed the merest tensing of his form, knowing that he had heard the new sounds as well and was listening intently. Having only been in England less than two years, the Gurkha would have no idea what he was hearing.

A human voice making soft hushing noises silenced the ferret.

The poachers.

As Hugh Mathers had told her, these game thieves often used weasels in their work. By sending a jill, a female ferret, down into the burrow to chase rabbits into net traps staked over the other openings to the warren. The rabbits, thinking they were rushing to freedom, instead found themselves entrapped in net bags cunningly set atop their escape routes.

Arabella looked to Rahul who was already moving, as silent as a ghost, into the grass. She walked carefully, placing her feet so as not to cause the stalks beneath her boot heels to rustle. One eye on the advancing Gurkha and one eye ahead to look down the barrels of the punt gun.

The whispered sound of a pair of men speaking grew closer and louder. The chuckling tone told her they’d had some success in their hunt. She caught no accent or distinguishing features in their hissed dialogue, their voices kept low so as not to alarm the rabbits or risk discovery by the legal landholder’s men.

These might or might not be the men who ended the life of the poor gaffer down south county. She hoped it would not turn out to be any of the estate’s tenants or their offspring. Though she’d explored every corner of her father’s holdings, she was still not familiar with all the farmers or the residents of the village of Brigham-on-Dee. All subjects of the sixth earl and, by association, herself. It would not be in the best standard of noblesse oblige were she to engage in battle with some local youngsters. Particularly if one of them came to harm or worse.

She raised the barrel of the punt gun, holding it close with her finger resting outside the curved trigger guard as she’d been taught. Rahul was out of sight and she was more concerned with him not coming to harm than with the poachers escaping.

In searching the dark for the source of the voices, as well as for her father’s loyal retainer, she neglected the ground before her. Her booted foot sunk into a rabbit hole, unbalancing her.

Unceremoniously, she was dumped on her derriere with her lips pressed tight to contain a yip at the sudden pain lancing up from a twisted ankle. The sound of her fall brought the men below to abrupt silence. The grass swished below as the poachers climbed the hill to investigate. The silhouettes of two men took shape against the overcast sky. Shadows cast by the gibbous moon fell over her as she thumbed back the hammers of her piece.

“’allo, poppet,” said one of the men with an ugly chuckle.

“Lovely wee coney we’ve snared, eh?” the other said, the leer plain in his speech though his face lay in shadow beneath the bill of a filthy cap.

The light of the moon waxed as the winds thinned the clouds above to gossamer. The men were dressed in black with burnt cork smeared on their faces and caps pulled low over their brows. One of them had a thatch of blond hair poking from beneath his cap. Each had a shotgun cradled in their arms. One of them raised a double-barrel trained on her.

“That’s too big a gun for you, lass,” the blond cooed. “Best you be laying it down before you do me or me brother an injury.”

The dark behind them stirred with movement.

Rahul emerged from the gloom to kick a boot toe into the back of the blond’s leg, dropping the man to a kneeling position. The younger poacher, brought to his knees and taken by surprise, allowed Rahul to get his powerful arm around the man’s neck. The gleaming blade of a curved Khukuri dagger held across the blond’s throat.

The other poacher, a stouter, older man, had no idea who or what the subedar was or the significance of the unusual blade held to his mate’s windpipe. He raised his shotgun to his shoulder and trained the sights on the Gurkha with shaking hands.

“Don’t be movin’ a hair, lad,” he said. “I got this nigger dead in me sights.”

The blond under the knife let out a strangled mewl.

“Tapā’īṁ sārnuhōs. Ū marcha,” the subedar said, his voice low and even. His meaning was clear despite slipping into his native Nepali.

Arabella saw the older man’s shoulders tense as he leaned forward to aim at what he could see of Rahul behind his mate. From her seat on the ground she discharged one of the punting gun’s barrels. The cascade of lead balls that erupted from the gun, a charge meant to bring down winged fowl by the dozens, and lifted the poacher from the ground bodily. Arabella was knocked flat on her back by the massive recoil of the weapon.

Simultaneously, with a move as smooth as a casual gesture, Rahul slid the razor-sharp blade across the throat of the younger man.

“Your father will be most cross,” Rahul said.

“What are we to do now?” Arabella said, standing up with the support of the punt gun set butt-first on the earth. She smoothed her skirts, dismayed at the blood shining black on the cloth of her pinafore.

“We bury them,” the Gurkha shrugged.

“I suppose that’s why you brought a shovel,” she sighed. A Gurkha always seemed to have a shovel handy.