Episode 3

Man and Boy

Young Joe Wiley’s first memories were of fights. He sometimes thought he was born fighting.

He was one of a rabble of bastards living in the camps that came and went outside Bent’s Fort. They lived like dogs on the scraps and leavings of traders, trappers, hunters, Indians and soldiers. Sometimes they even fought with the stray dogs for a sliver of meat or a buffalo joint. Mostly they fought each other and often to the amusement of the men who made rendezvous around the collection of adobe buildings. They lived in lean-tos, tents and wickiups.

Joe was remarkable for being purebred white. Most of the other unwanted children were from one of the tribes or of mixed blood. They were left behind by squaws who either died or abandoned them to live or die. They were the unwanted product of laying with soldiers or trappers in exchange for a strip of cloth, a length of copper wire or a drink of company rum. Girls died soonest. Only the toughest of the boys made it to adulthood.

And Joe was a tough one, an untamed cub who could snatch a greasy handful of meat and be away before the others could catch him. Or, failing to escape with his prize, would attack with teeth, fists and feet until he was either beaten down or left in peace to chew his slice of gristly steak.

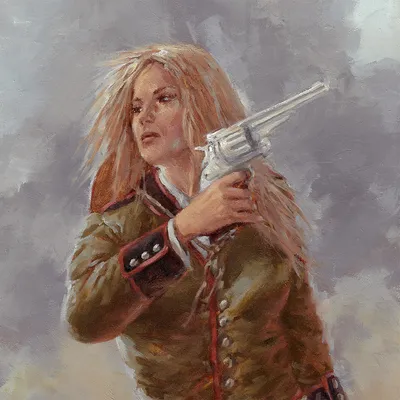

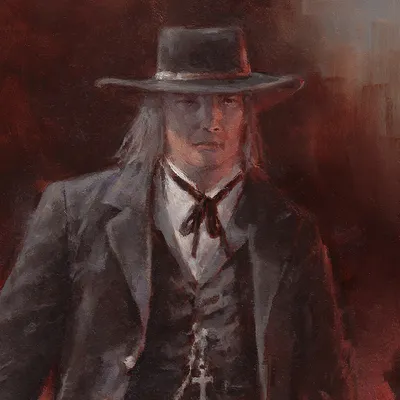

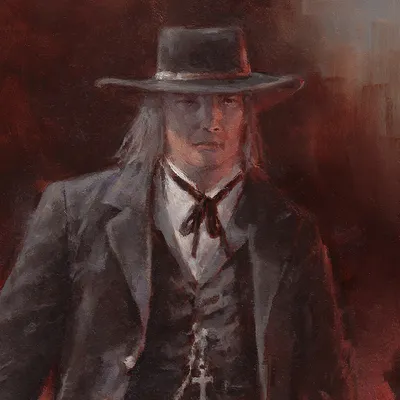

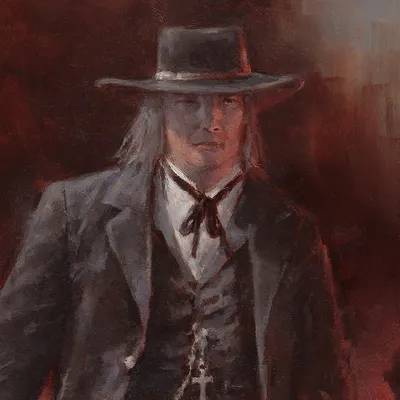

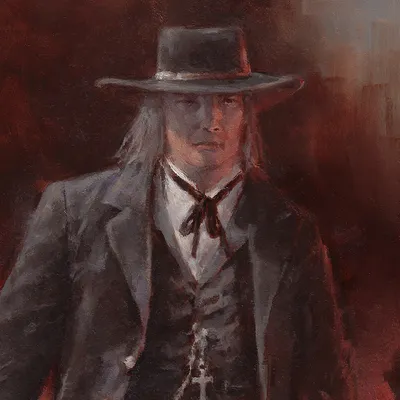

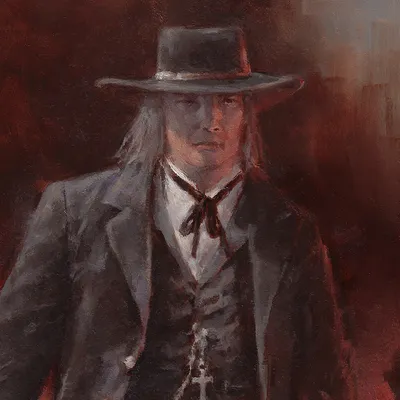

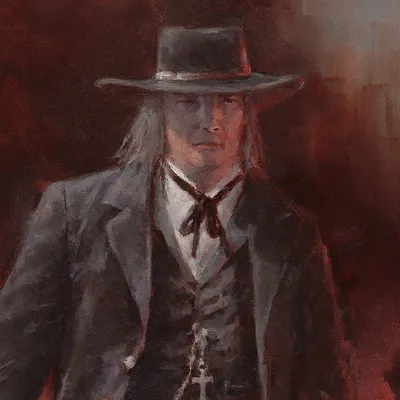

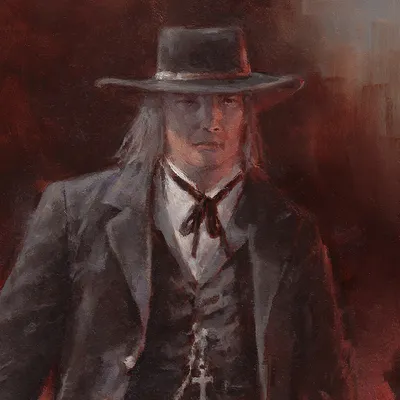

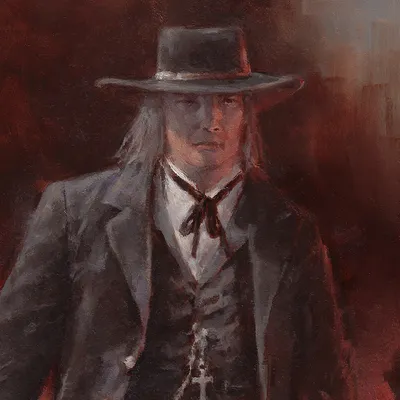

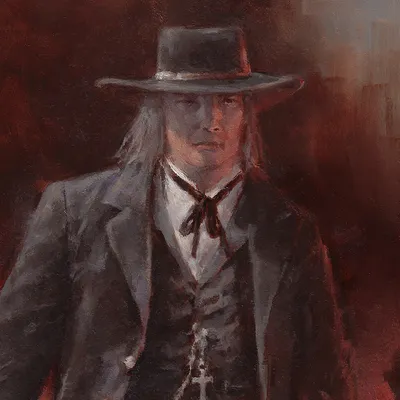

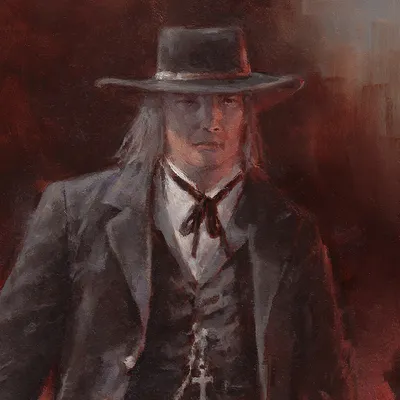

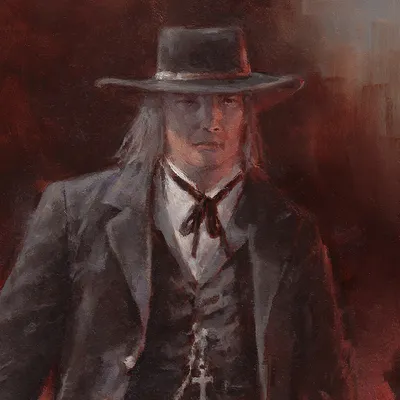

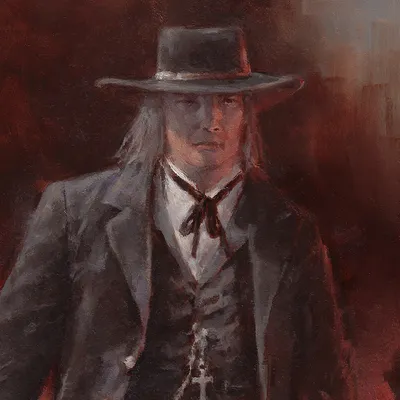

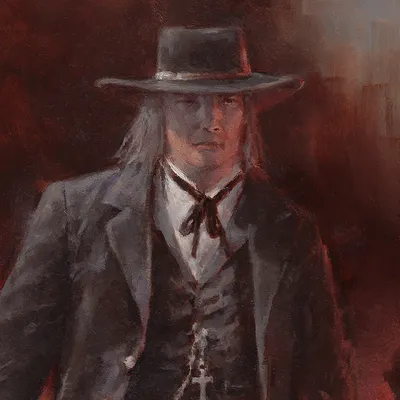

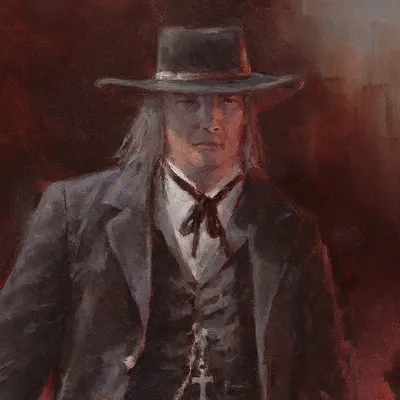

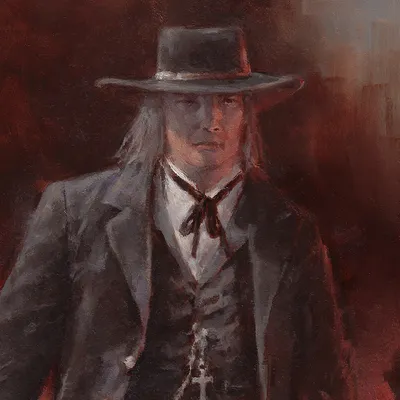

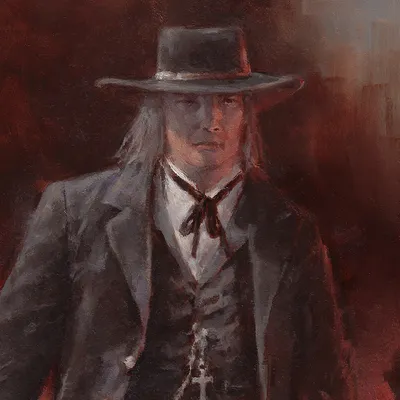

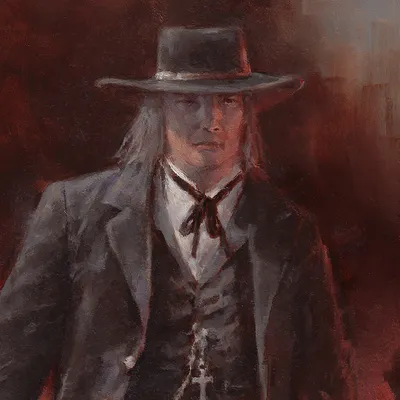

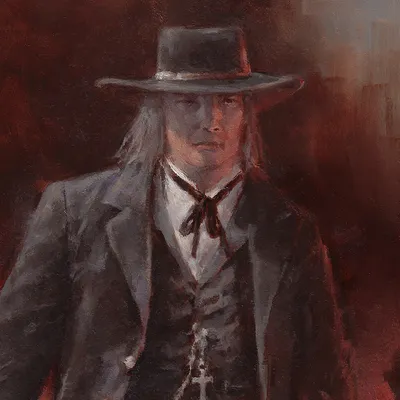

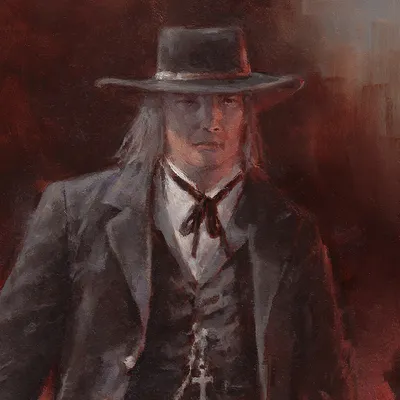

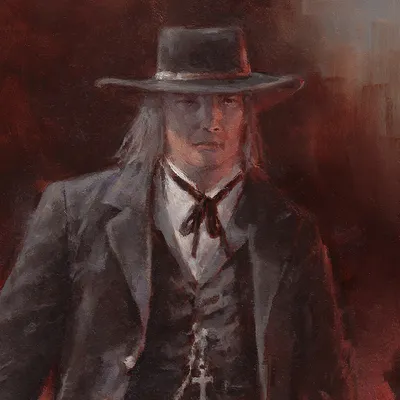

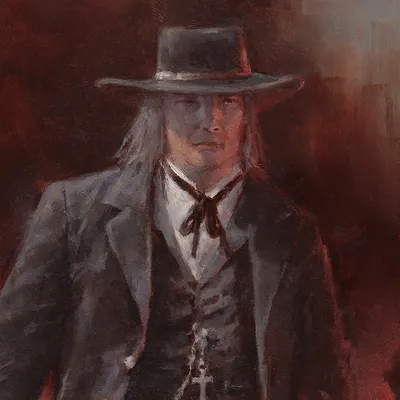

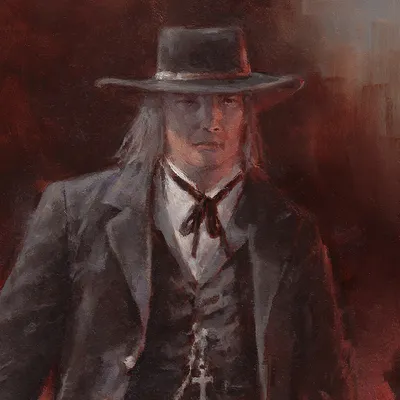

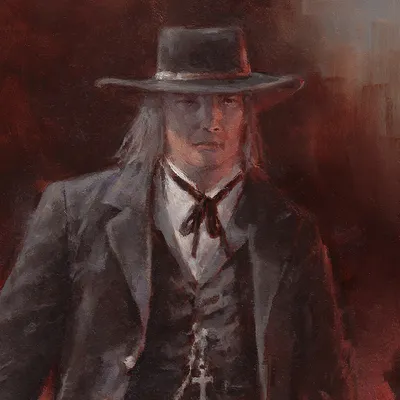

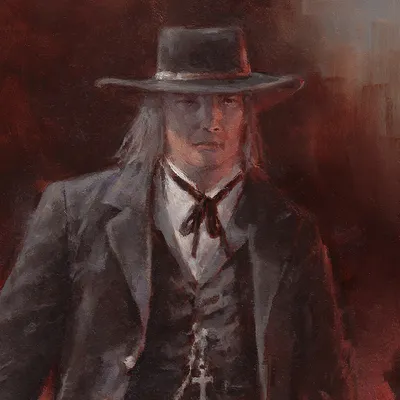

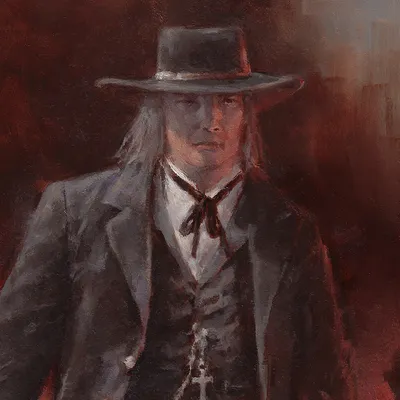

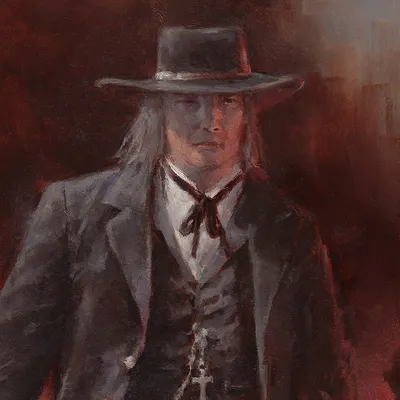

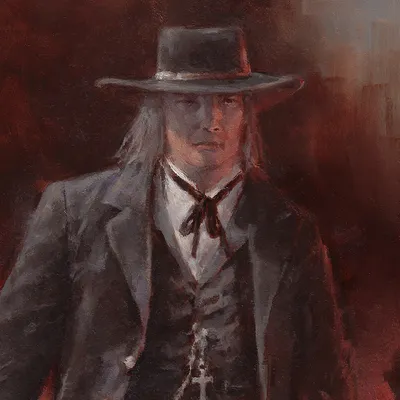

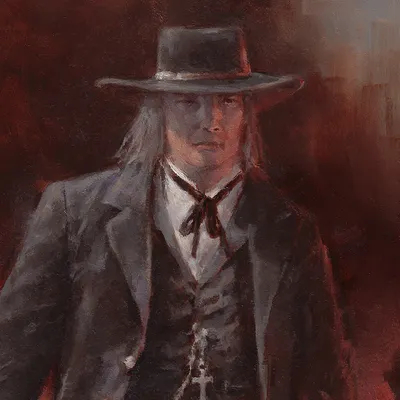

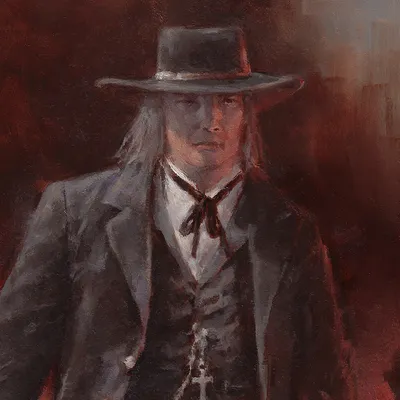

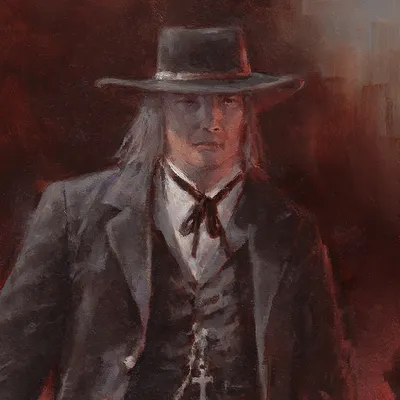

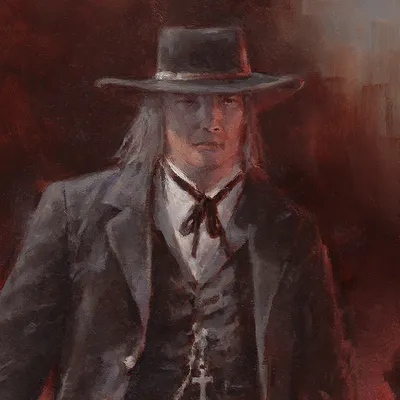

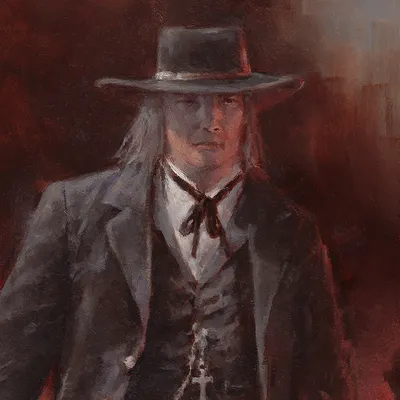

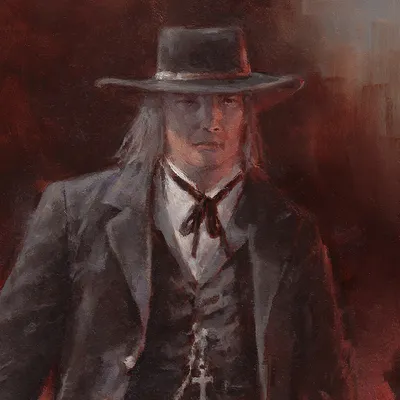

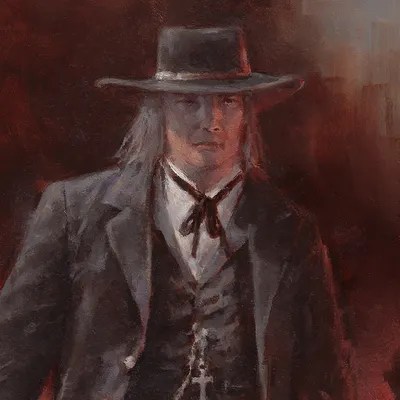

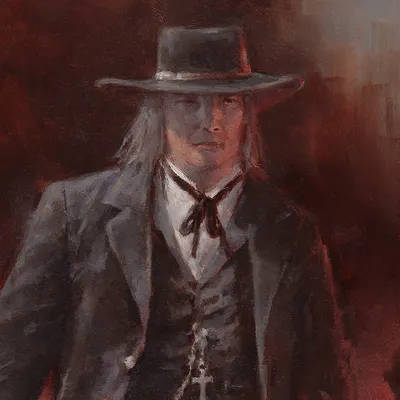

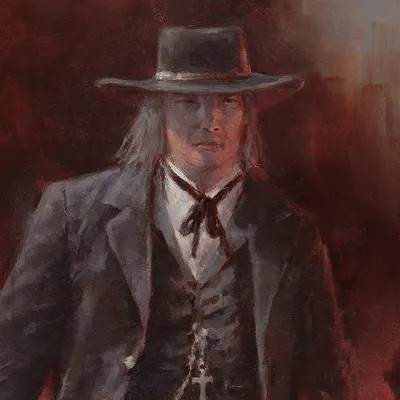

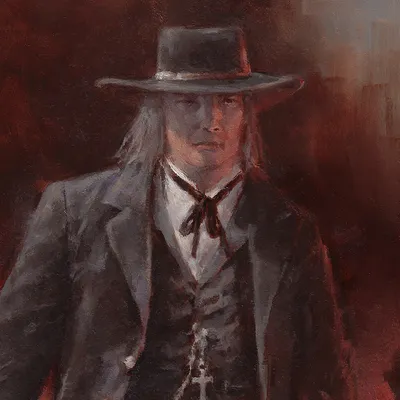

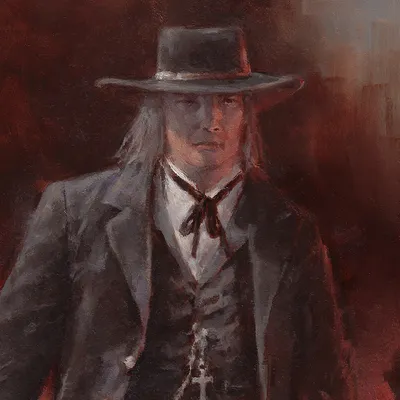

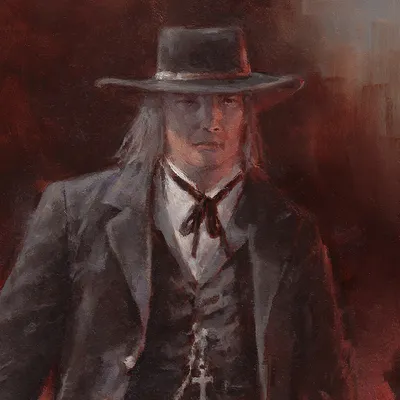

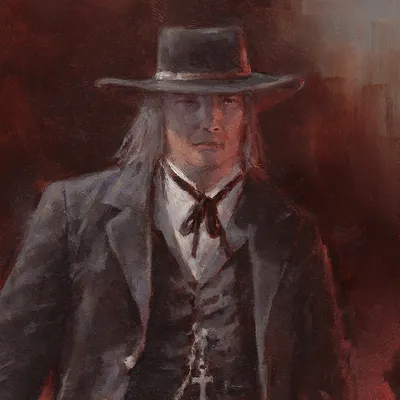

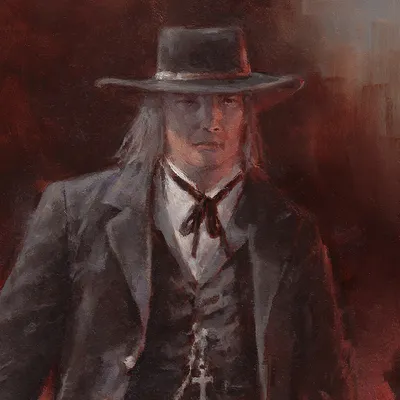

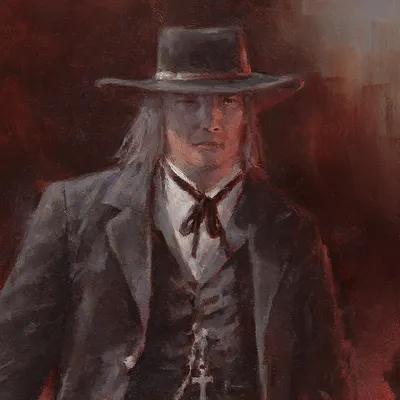

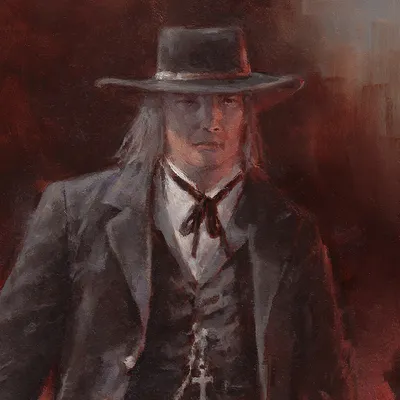

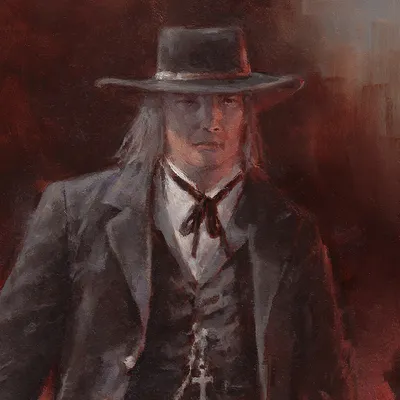

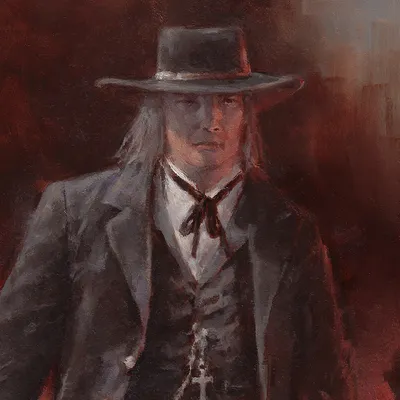

It was his feral nature and fearless stripe that made Ben Temple take notice of him. That and Joe’s mane of white, blond hair atop the filthy, half-naked hide of the bestial child. At the time Ben was making his living as a buffalo hunter under contract to the army. He was at Bent’s Fort often on his rounds, returning to the post with ox carts loaded down with trimmed meat to be salted and tanned hides to be traded.

Temple and his crew of hunters and skinners would stay a week or more in camp near the fort. They’d drink and smoke and rut with squaws before setting out north or south or west to follow the herds. They’d fight as well. With other trappers and hunters or soldiers or each other. Men died by the campfires, shot down or brained or gutted over the remains of a bottle or the attentions of a whore. Sometimes they died for no reason that anyone could recall. The only thing that anyone could remember was whether it was a good fight or a bad fight. Did the man who lost die well or die poorly was the only consideration. More than skill or toughness, the men who looked on wished most dearly that the man who fell to the fists, blade or ball not die whimpering and so bring shame to them all for having seen it happen.

So, it was a fight that first made Ben Temple pay closer mind to the towheaded bastard he’d seen running around the camps on previous visits.

One night, Joe had leapt for a rib of bison discarded by a drunken hunter. It was a long bone with a clump of stringy meat still clinging to one end. He jumped, hands clawing, only to take the sole of a foot in the face that set him rolling. A taller, older boy picked up the scrap and walked from the shared cook fire. It was an Indian named Stork for his height. He was two heads taller than Joe and a few years older. Joe charged him anyway. The pair tumbled to the ground together with feet and fists flying. They rolled as one toward the fire. Hooting and calling, the men seated in a ring rose to make way for them.

Ben Temple watched the boys fight over the rib even though it had already vanished from where it was dropped in the dirt; taken by another boy who raced away into the dark hugging the prize to his chest.

The men around the fire shouted and laughed as the boys grunted and squealed, locked in combat. Ben shouldered through the mass for a closer look. The smaller boy drove a knee into the other’s groin and landed his full weight on it while, at the same time, hooking a thumb in the other’s boy’s mouth and pulling hard at a corner. Stork pawed for young Joe’s eyes, squealing at the pain lancing up from his crushed testicles. He rocked back and forth, jerking to escape the terrible pressure but the smaller boy rode him with a tenacious fury. Joe snapped at the fingers of the reaching hands, taking a pinkie between his teeth and biting down hard. With a vicious yank on the soft flesh of Stork’s cheek, young Joe ripped a gash in the corner of his mouth. A geyser of blood sprayed up painting Joe crimson. Stork let out a gurgling scream and pounded the ground with the flat of his hand until the boy stood up, releasing him.

A roar rose from about the fire, an animal exultation at the bloody spectacle from a hundred throats. Joe got pats on the back and men ruffled his hair like a prized fighting dog. They fed him with strips of roasted meat and wild potatoes and corn mush. They pressed him to sip from their bottles until Ben Temple stepped in to pull the boy away.

“You’ll kill him with that liquor, you idiots,” Ben growled. And, drunk as they were, they took Ben’s rebuke in high spirits.

“What’s your name, boy?” Ben said.

Young Joe remained mum, mouth chewing the fine steak he’d been given. Face smeared with mush and grease.

Ben spoke to the others. “Does he have a name? Anyone hear know a name for him?”

“I mostly hear him called Wily Joe. ’Cause he’s the slickest of all these little shits.” This from a pie-eyed soldier, speaking with a lazy Tennessee drawl.

“Joe Wiley. Suits you,” Ben said, a thumb under the boy’s chin to study his face.

And they were together, man and boy, from that night forward.